New Twist in Richard Glossip Case Raises Questions About Future of Lethal Injections

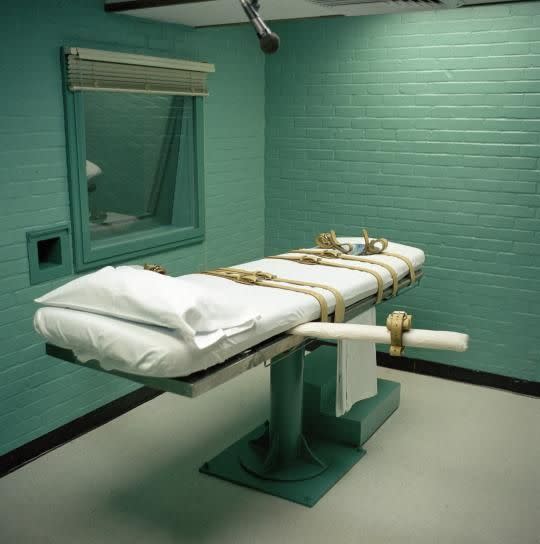

A typical lethal injection chamber. (Photo: Corbis)

On Wednesday, Sept. 30, Republican Gov. Mary Fallin of Oklahoma granted a last-minute stay of execution for Richard Glossip, the man whose name appeared before the Supreme Court earlier this year in a case to determine the constitutionality of the controversial drug midazolam as a lethal injection ingredient used by the state.

Fallin issued her stay minutes before Glossip’s scheduled execution (he was prepared and pacing in his death cell, wearing only boxer shorts), after it became apparent that the final drug in the state’s approved three drug protocol, potassium chloride — which is injected to stop the heart and cause death — had not been procured for Glossip’s execution. Potassium acetate, which is another drug altogether, had been mysteriously substituted in its place.

The case took another twist on Thursday afternoon when Oklahoma Attorney General E. Scott Pruitt asked that Glossip’s execution — and the two other executions scheduled in Oklahoma during the month of November — be suspended indefinitely so that his office could investigate the Oklahoma Department of Corrections acquisition of a drug “contrary to protocol.”

Richard Glossip. (Photo: Oklahoma Department of Corrections)

“Because of the secrecy [surrounding the administration of the death penalty], we can only read through the lines of what we know and read,” Deborah W. Denno, the Arthur A. McGivney Professor of Law at Fordham University School of Law and a leading expert on the legal issues surrounding the death penalty tells Yahoo Health. “The secrecy is going to shield a lot of information that would be very revealing about what happened.”

What we do know, however, is that this latest news in the story of Richard Glossip and his death penalty sentence is yet another variation on a theme of lethal-injection ineptitude that has been happening for years now in the United States. “There are only so many times they can say something was an isolated incident or an accident,” says Denno. “If you look at lethal injection from the very beginning, there have been endless ‘isolated incidents.’ At some point, it’s not an isolated incident but extraordinary recklessness.”

The Oklahoma protocol requires an inventory of everything used in an execution 48 hours before the execution. “Clearly that didn’t happen, since [the Oklahoma Department of Corrections] didn’t realize they had the wrong drug until very close before the scheduled execution,” Megan McCracken, the Eighth Amendment resource counsel with the U.C. Berkeley School of Law’s Death Penalty Clinic, tells Yahoo Health. “There was definitely a violation of protocol.”

After the infamously botched execution of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma in 2014 (Lockett suffered a prolonged death and was in obvious pain as he gasped for air), during which the execution team failed to follow the written protocol, the state revamped its protocol to assure the courts and the public that necessary changes had been made to fix what was broken. And yet, the slew of stays of execution show “the same level of carelessness all over again, and this raises significant concerns about this Department of Corrections’ ability to appropriately carry out executions,” says McCracken.

Potassium acetate, the ingredient that was going to be used for Glossip’s execution in place of potassium chloride, “is a salt — used therapeutically to replenish electrolytes in people who require an IV supplementation,” Kelly M. Standifer, of the University of Oklahoma College of Pharmacy explained to CNN. “Chemically, it’s in the same family as potassium chloride. They are formulated, however, in different concentrates.” And it’s never before been used for lethal injections.

“It’s just one problem after another.”

There are at least two ways executions can go wrong in a way that implicates constitutional protections. The first is if the execution is not carried out properly, or what’s known in the courts as maladministration. The second is if the drugs don’t work the way they need to work. “In Oklahoma, we have a confluence of both of these things,” says McCracken.

The execution of Kelly Gissendaner in Georgia on Tuesday — which was delayed for six months after it was discovered that the sedative to be used in the state’s protocol appeared uncharacteristically cloudy — is further evidence that when it comes to lethal injection, “it’s just one problem after another,” says Denno. “Once it looks like we’ve gotten rid of one problem, other problems pop up.”

Conspiracy theorists could surmise that this ineptitude is intentional, motivated by rebellion among Department of Corrections employees. But the truth is shockingly simple: “This process is being delegated to people and departments incapable of following the protocol,” says Denno. “They’re not rebelling against it: It’s just a matter of not having properly trained the people tasked with carrying it out.”

Which is why, Denno concludes, “it should demonstrate to the public that no matter where you stand on the death penalty, even if you’re for it, you shouldn’t want a process that is so inept.”