11 Things Only Someone With Endometriosis Understands

(Photo: Getty Images)

When Michelle Johnson was diagnosed with endometriosis, she thought she had the flu.

“Winters here in Chicago are brutal,” she says. “So when I found myself very fatigued and lethargic with a bad fever, I thought it was just the weather.”

She ended up in the ER after the fever hit 104°F. After 9 hours of tests for life-threatening concerns like a ruptured appendix, she found out she actually had stage 4 endometriosis. Endometrial growths had gotten so large they were pressing on her kidneys, restricting the flow of urine, which had led to a kidney infection that caused the sky-high fever. She’d been having increasingly heavy and frequent periods, but she thought it was “part of being a woman,” she says. It wasn’t: “The doctors guessed I had had endometriosis for at least 10 years, unchecked, undiagnosed.” She was 33.

Related: 5 Reasons It Hurts Down There

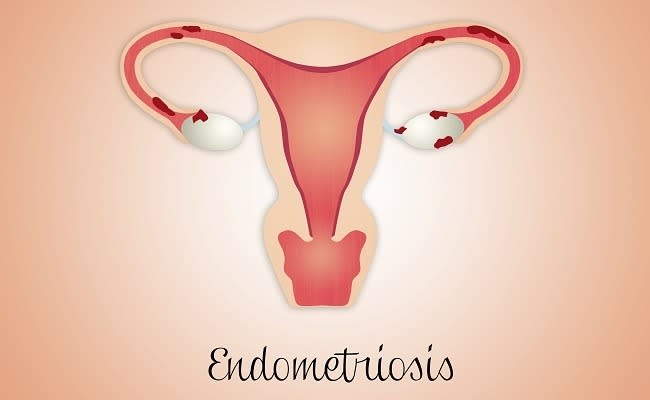

A little endometriosis 101 for the unfamiliar: Cells that typically grow in the lining of the uterus, called the endometrium, can end up in other places, where they really don’t belong, says Marc R. Laufer, MD, a Harvard professor, chief of gynecology at Boston Children’s Hospital, and the director of the Boston Center for Endometriosis. “Those cells implant in those other locations and cause pain if left untreated or undiagnosed." (Looking for more health news? Get your FREE trial of Prevention magazine + 12 FREE gifts.)

That’s because they grow—and bleed—as if they were still at home in the uterus. "Every time a woman has a period, there are these micro-periods happening,” says Tamer Seckin, MD, a specialist in endometriosis in private practice in New York and the co-founder and medical director of the Endometriosis Foundation of America. The immune system is altered in some way in women with endometriosis so that no matter how much swelling and inflammation the body sends to the pelvic cavity to try to clean away the blood that doesn’t belong, the implanted cells are still able to thrive, acting almost like cancer in many ways. Growths on the ovaries, called endometriomas or chocolate cysts, can permanently damage a woman’s fertility. Cysts may grow on the bowels, bladder, or, more rarely, even infiltrate the lungs.

There’s a ton we still don’t know about why this happens, but the predominant theory is called retrograde menstruation. The thinking goes that every month when a woman menstruates, some of the blood that leaves the uterus escapes into the pelvic cavity that surrounds the reproductive organs instead of leaving the body. But we—frustratingly—don’t know why a woman would experience retrograde menstruation in the first place. There seems to be a genetic link in some instances; if women in your family have always had painful periods, it’s worth considering the diagnosis before you write off your pain as a family legacy.

Related: 13 Ways To Lower Blood Pressure Naturally

We do know that endo can begin at a girl’s very first period, and that the most obvious symptom is pain with menstruation “in the magnitude of killer cramps,” Seckin says. Endometriosis is in no way “just” cramps (more on that in a sec); not only is the pain debilitatingly severe, it’s also often accompanied by nausea, vomiting, constipation, back pain, pain during sex, and particularly heavy menstrual bleeding.

One of the biggest challenges for doctors, Laufer says, is there’s no way to test for endometriosis in its earliest stages; it shows up on scans only when it’s advanced, which makes preserving fertility even trickier, he says. Part of what he and his Boston Center for Endometriosis colleagues are researching is surgery-free ways to diagnose the disease early on.

In the meantime, if we’re going to help the 6 to 10% of women of reproductive age who have endometriosis, we’re going to have to stop being so hush-hush about it. What are we afraid of, a little period talk? Psh. Here are a few of the many things only a woman with endo truly understands. Familiarize yourself so you can be a better friend—or realize you need treatment yourself.

Endo pain is not a “normal part of being a woman,” so there will be none of this “suck it up” nonsense. Thanks, though.

(Photo: Getty Images)

Before you say, “Oh yeah, I have bad cramps, too!” consider Amy Day’s experience finding out she had endometriosis: “Over the course of the year after I went off the pill, each month my period got worse than the month before. One month, I basically spent 2 days lying on the bathroom floor, unable to move or eat or drink,” the naturopathic doctor, now 41, says. She was just 27 at the time, and when she had surgery mere days later, her doctor removed an endometrioma the size of a grapefruit. “I was offered every painkiller on the block because I had just had surgery,” she says, “but that level of pain was nothing compared to the amount of pain I had been in previously.”

As many as 70% of women have some cramping with a period at least once in a while, Seckin says, but there aren’t many women who have cramps so severe they require narcotic pain meds or have to stay home from work. “So many young girls and young women especially are just putting up with painful periods and not getting the help they need because they think they’re supposed to deal with it,” Day says. “If a young girl feels disadvantaged in any way by a painful period, that’s not right,” Laufer agrees.

Related: 7 Reasons You’re Tired All The Time

And please spare us the “just get pregnant” business.

(Photo: Getty Images)

“I didn’t want to be on powerful drugs, so I asked for the most natural treatment available, and I was told I should have a baby,” Day says. “I was 28 years old, not ready to start a family, and told for a medical treatment to bring another human being into this world who I’ll have to care for and raise?!” Seriously, folks: Not the greatest reason we’ve ever heard to have kids.

Yes, getting pregnant can reduce some endo symptoms. With a bun in the oven, a woman’s progesterone levels are higher, and because endometriosis is fueled by estrogen, the surplus of progesterone can suppress the disease. That’s how this whole “just get pregnant” thing probably got started. But it’s not a cure. Nine months later, symptoms will return in most women—and she’ll have a baby to care for, too.

That’s assuming, of course, that a woman with endometriosis can even get pregnant to begin with. Somewhere between a third and half of women with endo won’t be able to because their reproductive organs will be so damaged by the disease. Among women who already know they’re infertile, 20% are likely to have endometriosis and not know it, Laufer says, “either because they haven’t felt the symptoms or they normalize the symptoms."

When Day was ready to start a family, she found she couldn’t.

Related: 5 Signs You’re Not Getting Enough Vitamin D

Getting a hysterectomy is a last resort, at best.

Since endometriosis stems from the uterus, it makes some sense to assume removing the uterus would remove the problem. A hysterectomy can be effective in lessening pain, but it’s still not a cure, considering cysts can grow on any number of other organs. The hope is to avoid hysterectomy, Laufer says. He’s treated teenagers who were told they needed the operation simply because their previous doctors were frustrated by their lack of options. "One should always seek out another opinion and consider something less radical,” he says.

Plus, many women with endo would still like the opportunity to at least try to get pregnant when they’re ready. “I did want to at some point try to have children, so for me a hysterectomy wasn’t an option,” Johnson says, although doctors urged her to consider it. “They were pushy with that; I knew I had to find an alternative.” She’s 40 now, and still hopeful. “I do still plan to have children; that’s definitely still in the cards for me,” she says. “If I find that’s not possible, adoption is very much a strong second option.”

There should be frequent-flyer perks in the operating room…

(Photo: Getty Images)

The best possible treatment for endometriosis starts with excision surgery, Seckin says, which removes the growths and their roots. (Another option is ablation, a process that essentially burns off the lesions with a laser, leaving the roots intact. It should really only be used in the early stages of the disease, if at all.) But because some endometriosis is either hard to see or hard to excise completely (or both!), sometimes surgery doesn’t get everything, or endometriosis comes back, and a second, third, heck, seventh surgery may be needed. Day has had two surgeries, 11 years apart. Johnson, a licensed massage therapist, has also had two, and says some of the women she works with as an advocate with the Endometriosis Association have had as many as 10.

…But surgery also isn’t a magic bullet.

Surgery helps, certainly, but there is no cure. “In my mind, endometriosis was this glob of something,” Johnson says. She, like many, assumed once the glob was out, life would go back to normal. Not only was it too dangerous to her other organs to remove 100% of her endometriosis, she’s also had a recurrence. “They take it out, but you still have a menstrual cycle, which feeds the disease,” she says.

That’s why many women use hormonal treatment, whether it’s a birth control pill or the vaginal ring, to “turn off” the menstrual cycle to keep lingering symptoms under control, Laufer says. On continuous hormones, a woman won’t have a regular period, and therefore shouldn’t have the endo pain associated with it. Experts recommend hormonal medications until a woman is done having kids. When fertility is no longer a concern, she can then reevaluate treatment based on how bad the pain continues to be. At menopause, the drop in estrogen tends to result in a drop in endometriosis symptoms, Laufer says, but pain may also continue later in life. “Nothing in this disease is black and white,” he says.

Many women with endometriosis rely on prescription painkillers—nothing else dulls the pain enough to allow them to carry on with their daily lives. But Seckin is concerned about addiction to some of these powerful drugs; in the care of less-experienced doctors, some women are told there’s no other option and are essentially bullied into taking meds they then come to depend on.

Related: 8 Things That Happen When You Finally Stop Drinking Diet Soda

This discomfort talking about—gasp!—periods is getting so old.

In many circles, it’s still taboo to talk about bleeding and vaginas and uteruses. But we wouldn’t shy away from discussing endometriosis if we called it, say, an immune disorder, Day says. Women with endo often deal with comments that they don’t look sick. “It’s not a disease you can see,” Laufer says. “You can’t see that a woman’s got this, yet she’s suffering.”

There’s a pervasive sense that the misunderstanding of endometriosis stems from the age-old association menstruation has with being somehow dirty or bad, Seckin says. Some doctors treat painful periods as a symptom of some underlying psychological issue—maybe things aren’t going well in school for a teenage girl, and her doctor implies her complaints are an excuse for her bad grades. “There’s a cultural misconception that when there’s pain with a period, it is all in a woman’s head,” he says.

It certainly makes dating extra tricky, Johnson says. Not only is endo a top cause of infertility, for many women it’s accompanied by incessant bleeding and pain so bad it can make sex nearly impossible—and what woman wants to bring that up on a third date? Johnson says many women she’s worked with tell stories of getting friend-zoned after having the endometriosis talk with a formerly interested guy. “It’s difficult to find a caring and compassionate partner,” she says.

Yes, you can talk back to your doctor…

Women with endo know it can take a while to find someone who truly listens, but they also know it’s worth it. Johnson says she’s “fired” about three different docs. Two years after surgery, still dealing with excruciating pain, she was told by her team of care providers that they didn’t know what else to do. “They had exhausted all the options from their limited knowledge of the disease,” she says. She was left to find an endo specialist herself, with the help of online support groups.

Even some ob-gyns don’t always comprehend the seriousness of endometriosis pain. “It’s a shame, but gynecologists are missing this disease constantly,” Seckin says. He suggests looking for someone who specializes in endometriosis specifically. “If you get blown off by your first doctor, go to another doctor,” Day says.

Related: 9 Proven Ways To Lose Stubborn Belly Fat

…But doing so can feel very isolating.

(Photo: Getty Images)

Being told by her doctors that they didn’t know what else to try was “very disheartening,” Johnson says. She started going to therapy for clinical depression, which she later learned was not uncommon among women with endometriosis. “If I have to live with this, and I can’t even get any consistent relief, if this is what my life has been reduced to, if the doctors can’t help me, what am I to do?” she remembers thinking. It can feel all-encompassing, she says, and it’s not uncommon for women with endometriosis to end their own lives. “It’s not difficult to spiral into that dark place.”

Indeed, chronic pain of any cause has been linked with higher rates of depression and suicide. “Many women are depressed because no one understands,” Seckin says. “Doctors have to have more compassion, more empathy.”

As if the pain wasn’t bad enough, sometimes it’s totally unpredictable, because that’s always fun.

After 3 or 4 months symptom-free, you’re riding high, confident you’ve turned a corner somehow. Then, Johnson says, you’ll be at work and out of nowhere start bleeding “quickly, suddenly, and aggressively.” Women with endometriosis learn to always be prepared, whether it means stashing sanitary napkins, pain pills, wipes, or those handy bleach-on-the-go pens in their purses and gym bags, she says. Because of endo’s unforeseeable nature, it’s constantly getting in the way of women’s social lives, she says. “You can make plans to go out—you bought the ticket, you’ve got the outfit—but the morning of, you’ll be hit with a flare-up and you can’t go.”

Eating well and getting enough sleep are non-negotiable.

(Photo: Getty Images)

After surgery and along with hormones, experts recommend approaching endometriosis care from all angles: A holistic approach to treatment can include working with a physical therapist to limit pelvic pain, adopting an anti-inflammation diet, even acupuncture, Seckin says.

Day advocates for clean living: She opts for green cleaners, eats organic, and keeps stress in check to quiet inflammation and pain. Johnson says even though a little gentle exercise may help with the pain, sometimes being active exacerbates it or brings on new bleeding.

We can’t say it enough: There is no cure.

Have we repeated this enough yet? Surgery can lessen some symptoms, and medications can help too, but nothing puts endo to rest for good. “There’s still some unspoken perception that surgeries and medications will make this thing go away,” Johnson says. “You have to redefine what normal is for you. It will never look like what it did before your diagnosis, and that is incredibly frustrating.”

By Sarah Klein

This article ‘11 Things Only Someone With Endometriosis Understands’ originally ran on Prevention.com.