What LGBTQ, Native American and other civil rights leaders learned from Black protesters

USA TODAY’s “Seven Days of 1961” explores how sustained acts of resistance can bring about sweeping change. Throughout 1961, activists risked their lives to fight for voting rights and the integration of schools, businesses, public transit and libraries. Decades later, their work continues to shape debates over voting access, police brutality and equal rights for all.

The 1960s was an era of revolt.

Native Americans occupied federal land and demanded to be seen.

Women marched for equal rights.

LGBTQ people fought police violence in New York City.

Mexican Americans led walkouts and protests to highlight farmworkers’ rights and education inequalities.

Asian Americans formed the Yellow Power Movement to champion equity.

Each of these movements were inspired by and sought to emulate the many African American leaders who stood up to segregation, organized against oppression and helped usher in a new United States during the civil rights protests of the 1960s.

These activists risked their futures to make a better nation for all Americans. When their lives were at risk, they remained steadfast.

Here are some of their experiences:

‘We were the pioneers’

Marion Kwan, 79

In 1968, Marion Kwan joined other Asian Americans and students of color in a strike against San Francisco State College. Their goal was to have more diversity on campus and an ethnic studies program. In the late ’60s and ’70s, Asian Americans came together to advocate for better employment and education under the Yellow Power Movement. Kwan eventually moved to Mississippi and joined the Delta Ministry, a project that aimed to train and educate low-income Black people on the importance of voting and activism.

“I grew up in San Francisco's Chinatown. I knew nothing about Blacks or other races other than Chinese and white tourists. But, during the late ’50s and ’60s, Black power was evident, and like other communities, Yellow Power was introduced. We were the pioneers, movers, shakers, breaking the ground for young people today. We fought for workers’ union rights. We organized the famous San Francisco State University strike. We encouraged our people to bring issues before City Hall and get involved in politics.

"But I didn’t join the movement because it was a movement. When I left San Francisco and went to Mississippi, I witnessed the inhumane treatment of people. I intuitively became an instant ally to the Black community because I can identify with them and they can identify with me. I learned from the heroes in Mississippi. They had lived there in terror while still taking me into their homes, so I had a place to sleep and do freedom work.

"I remember one hot evening, sitting on the front porch with Mrs. Simmons (a Black woman who houses freedom fighters), and she told me that on a similar night, she had heard of a slow engine of a car passing by her porch, where we were sitting. When she heard the sound of the car, she knew it was a Ku Klux Klan car. She kept as quiet as she could, frozen in her rocking chair. Then she said she saw a large cross being burned at the nearby church. She kept quiet till the car disappeared.

"It was these brief moments that the people in the Black community were willing to talk about that kept me going all these years."

‘I knew that plenty of people would love to shoot gay people’

Martha Shelley, 77

Martha Shelley became one of the founders of New York’s Gay Liberation Front, a coalition of activists working to fight against discrimination against the LGBTQ community. Their work was fueled by the Stonewell riots, which began in June 1969 as a response to a police raid at Stonewell Inn, a gay bar in New York City. Shelley helped organize protests, wrote for the Gay Liberation Front newspaper and was active with the Daughters of Bilitis, a lesbian civil rights group.

“My best friend in junior high was Black and I was very much aware of the civil rights movement, but I was too young to do anything like join the Freedom Rides. So when it was happening, I was a kid in high school, and my parents would not have approved of me getting on a bus and going down South to risk my life.

"In 1969, somewhere in June, came the Stonewall riots. I had become the public spokesperson for the New York chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis because I was the only one willing to be out in public. Other gay organizations at the time wanted basic civil rights: They wanted to be accepted into the mainstream society, be treated like anyone else, have nice houses in the suburbs, get jobs, be married and not be harassed. Well, those of us on the Gay Liberation Front wanted a lot more than that.

"The first march that was organized happened one month after Stonewall. I was scared because I’ve lived through Martin Luther King being shot, Malcolm X being shot, and I knew that plenty of people would love to shoot gay people. I was going to be standing out in the public street being openly gay. But 400 people came, and I knew this was just the beginning of what was in store for us. The day after the march, a few of us got together and someone said ‘Gay Liberation Front,’ and that was it. We started meeting, held dances, did demonstrations and put out a newspaper.”

‘A more powerful position in society’

Harry Gamboa Jr., 70

Harry Gamboa Jr. led demonstrations in East Los Angeles, including the Chicano Blowout, a series of protests against inequality in Los Angeles Unified School District high schools. Fueled by centuries of discrimination against Mexicans and the Eisenhower administration’s racist deportation campaign Operation Wetback, Chicano activists increasingly began to fight for better labor conditions and education in the 1960s and ’70s.

“During the walkouts, my role was to write the list of demands, publish the materials, distribute the materials and organize. As a high school student, the goal was to bring awareness because a lack of awareness would lead to the death of my cohorts in the streets. The focus was how it would be possible for people to obtain a higher education, which would lead to a more powerful position in society.

"Former President Richard Nixon had a great antipathy toward Mexican Americans. He was involved in establishing Operation Wetback. The United States would go out and simply arrest and deport anyone who appeared to be Mexican, whether they were citizens or not.

"We felt like we were promoting the U.S. Constitution, the Bill of Rights and human rights through those protests. I think it was amazing that 300 students walked out of Garfield High School. Everyone demanded a better education. When we went out, we were greeted by several hundred parents and family members who supported us."

‘Black people were fighting collectively’

Kathie Sarachild, 78

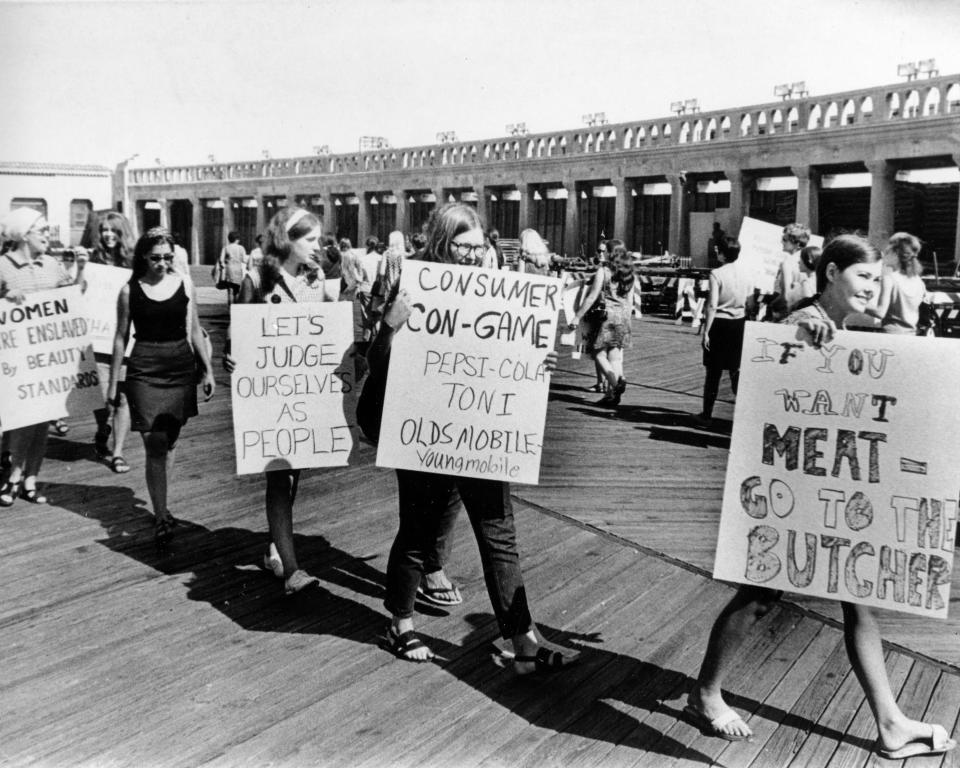

Kathie Sarachild and four other women organized a protest at the Miss America pageant in 1969 where they carried a large “Women’s Liberation” banner. Sarachild also became a member of the Redstocking, a radical feminist nonprofit that advocated for women’s rights. In the late '60s, the women’s liberation movement rose in prominence through these and other protests.

“What really stuck with me was one of the times I was arrested with 800 other people in Jackson, Mississippi, for parading without a permit but was actually marching for the right to vote.

"When they arrested us, they separated the white women from the Black women. The white women were going to be put in jail and the Black women in a stadium.

"My eyes were open to how important courage is, and I had things to learn about it. When the women were being separated, the fifth white woman refused to be separated. She sat down and they dragged her for about 300 feet on the floor. After that, every single white woman behind her also refused. It was a wonderful show of solidarity, and that stuck with me all of my life.

"Women's liberation didn’t only learn from the civil rights movement, but SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was where I first heard the term. So the women’s liberation movement, at least my part of it, felt like we were on an assignment from SNCC.

"I had just gone down to Mississippi in 1965, and someone who was still on SNCC’s project team knew I was a feminist because I had been complaining over the summer about men not sharing the housework enough. He came running after me, saying, ‘Kathie, you’ll be so excited to know that everyone is talking about women’s liberation.’

"When I heard that phrase ‘women’s liberation' in the context of the grassroots Mississippi movement, Black people were uniting and forming an organization. They didn’t just fight their problem individually, but they were organizing. It suddenly put the idea in my mind that that is not something that you do by yourself, but you create a movement and fight collectively like Black people were fighting collectively.”

‘It was like a big adventure’

Lenny Foster, 73

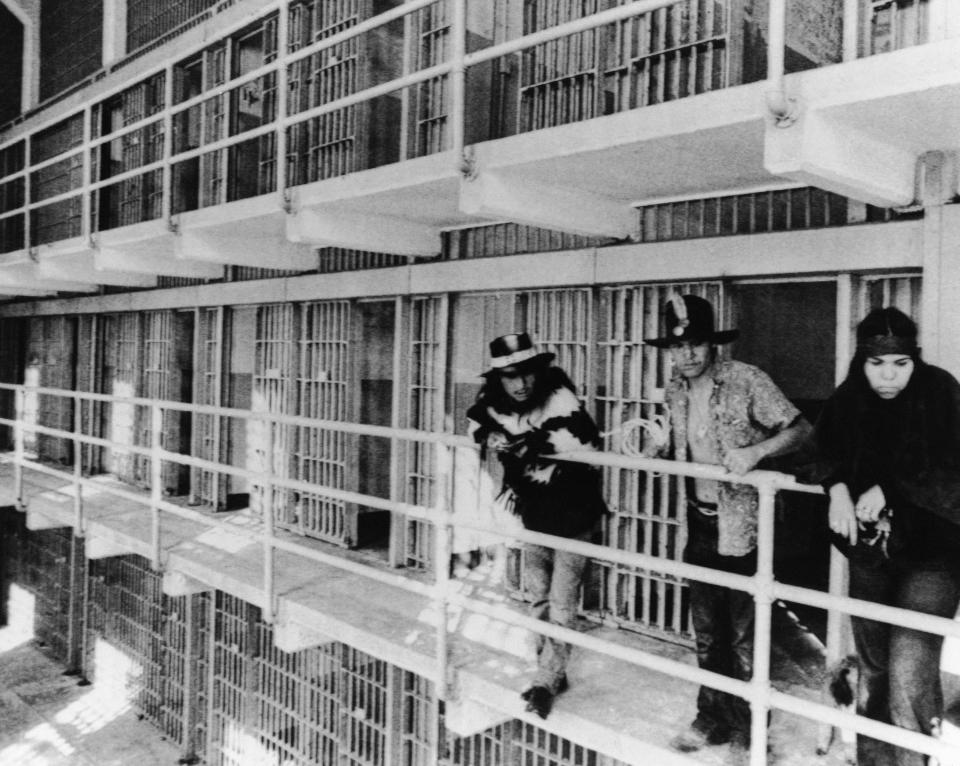

In 1969, Lenny Foster and dozens of other Native Americans occupied Alcatraz Island in San Francisco. Throughout history, the U.S. government removed Native Americans from their land. In 1968, the American Indian Movement was formed to address poverty, land rights and discrimination against Native Americans. In 1972, Foster and other activists occupied the Bureau of Indian Affairs building near the White House to protest President Richard Nixon’s administration.

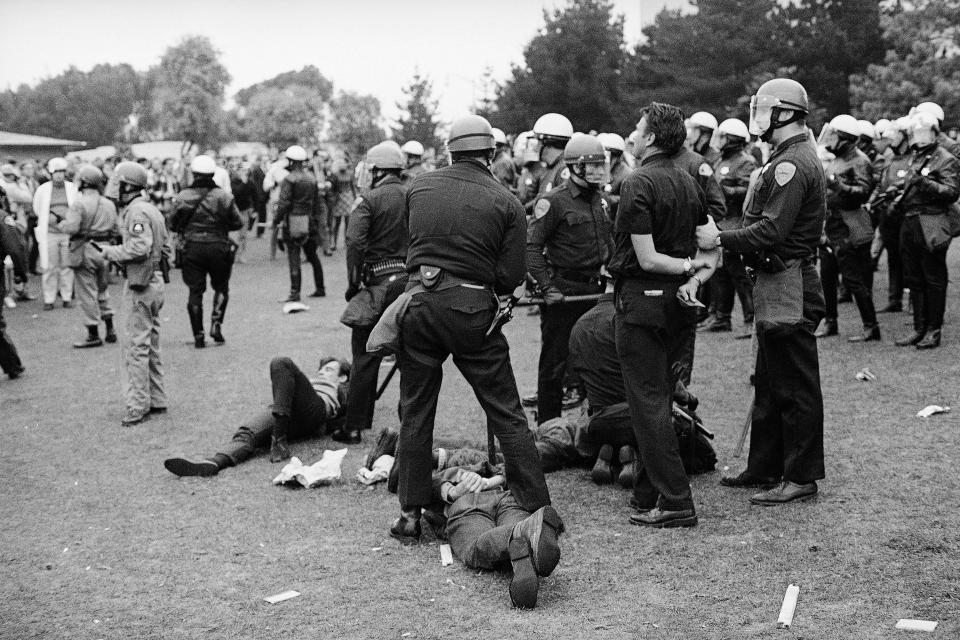

“We had developed a 20-points paper where we expressed our concerns. They were documented and written. We wanted to submit it to former President Nixon, but no one took the American Indian Movement seriously. So, we met up at the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington, D.C., to discuss how they wouldn’t let us meet with President Nixon. Soon after, we were confronted by the police.

"They told us to leave, and that's when a fight broke out. We decided we were going to sit down and not leave the building. We used the furniture to block the windows and doors in case they tried anything else. We were there for about a week before we finally got the attention of the Nixon administration and they agreed to meet with us.

"Many of us were young, so it was like a big adventure. It was a moment in history.

"The civil rights movement was very important. The African Americans’ push for civil rights (was) very important for them to be treated as human beings, because that was not done. Therefore, they had to resort to protests and demonstrations. We saw a similar thing with the American Indian movement.”

‘No one would hire us’

José Angel Gutiérrez, 76

José Angel Gutiérrez was a student at St. Mary University in San Antonio when he co-founded the Mexican American Youth Organization to champion Mexican American rights. Mexican Americans had endured and fought against discrimination for centuries but, in the late ’60s and ’70s, activists and organizations emerged, identifying as “Chicanos” with new tactics and goals. Farmworkers organized hundreds of strikes and boycotts against work conditions. Students led walkouts and fought against education inequality. MAYO played a significant role in the Chicano movement through voter registration and organizing school walkouts in Texas.

“In Crystal City, Texas, the railroad tracks were in the middle of the town and divided it. The west side was where the Mexicans were and on the east side was where the whites were. So Texas was segregated and every other Mexican kid experienced discrimination. So, Black and Chicanos, you can say, went through similar things.

"Back then, you had the poll tax, which meant you had to pay to vote. You had the advance voter registration that you had to do between Oct. 1 and Jan. 31 of the year preceding the election. In other words, you had to pay the poll tax even though you didn’t know who was running. These were repressive means that were in place. So, in 1962, this group of people from San Antonio from the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations came into town and said: ‘It’s about time you elect your people into the City Council and take over the government. You’re 80% of the population and you’re all potentially eligible to vote if you pay the poll tax.’

"We started organizing and that campaign became ‘Los Cinco Candidatos’ – the five candidates. So, the campaign was about taking five at-large positions in the City Council, and we won.

"Then I went to St. Mary for school and stayed there till I got my Ph.D. in government. But I was still thinking about Crystal City. So, while studying at St. Mary, I formed the Mexican American Youth Organization because every Mexican kid there had the same experience I did with discrimination. We were always talking about that and ended up doing three walkouts. But then I got drafted.

"I came back for Christmas and my mother wanted us to go to Crystal City. While we were there, we got this alarming bang on the door. The person said, ‘Your farmhouse is burning.’

"My father had this little ranch outside town. My wife and I were planning on moving back to Crystal City and taking over the school board, and that was the house we were going to live in, but it was on fire.

"So we went out there, the firefighters came out, but they wouldn’t put it out. They said, ‘It’s too late; it’s not going to work.’ When I asked if anyone was going to investigate this, I was told, ‘You know these things happen.’ I was really pissed.

"Eventually, we came back to Crystal City, but no one would hire us. They didn’t want us there because of the organizing we did in the past.”

Explore the series

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: What LGBTQ, other community leaders learned from Black protesters