Food Expiration Dates Are Terribly Misleading

By: Wil Fulton

Credit: Cole Saladino/Thrillist

There are three ways to approach expired food: with caution and trepidation, say “screw it” and eat it anyway, or say “aw hell no,” and toss your graham crackers out the window as soon as they are within 48 hours of the date stamped on the box.

Almost 90% of Americans will throw away perfectly safe and edible food the day it hits its “expiration date.” I used to be part of that percentage. I believed that if I consumed a food past its date, I would surely contract an unprecedented hybrid of smallpox, herpes, lupus, and E. coli, turning me into a bed-ridden, fly-covered zombie, which would thoroughly ruin all weekend plans. These dates are held as sacrosanct, but in many respects, that sentiment is just plain wrong.

Basically, I’m Morpheus, and I’m telling you your entire consuming life has been one big fat sham. This article is your red pill for food-based enlightenment. Take it.

More: The 17 Most Wasteful Things You Do in Your Kitchen… and How to Stop

Credit: Valestock/Shutterstock.com

It’s almost impossible to tell when the food you buy will become “unsafe”

In one episode of the (excellent) podcast 99% Invisible, host Roman Mars and crew examine the expiration date debacle themselves, and find that it is almost scientifically impossible to accurately predict when food you buy may become unsafe to eat. For instance, leaving milk in a hot car the day you buy it will ensure it spoils faster, and colder fridge temperatures can keep a carton of milk longer than others. There are just too many variables to peg a specific day.

They also clear up a long-held medical falsehood: old food almost never makes you sick, contaminated food is what will land you in a hospital bed (or grave). So, these dates, even with fickle dairy items, are not safety precautions. Deli meats, unpasteurized dairy, smoked seafood – these are the foods that may increase in contamination with time. Graham crackers? Not so much.

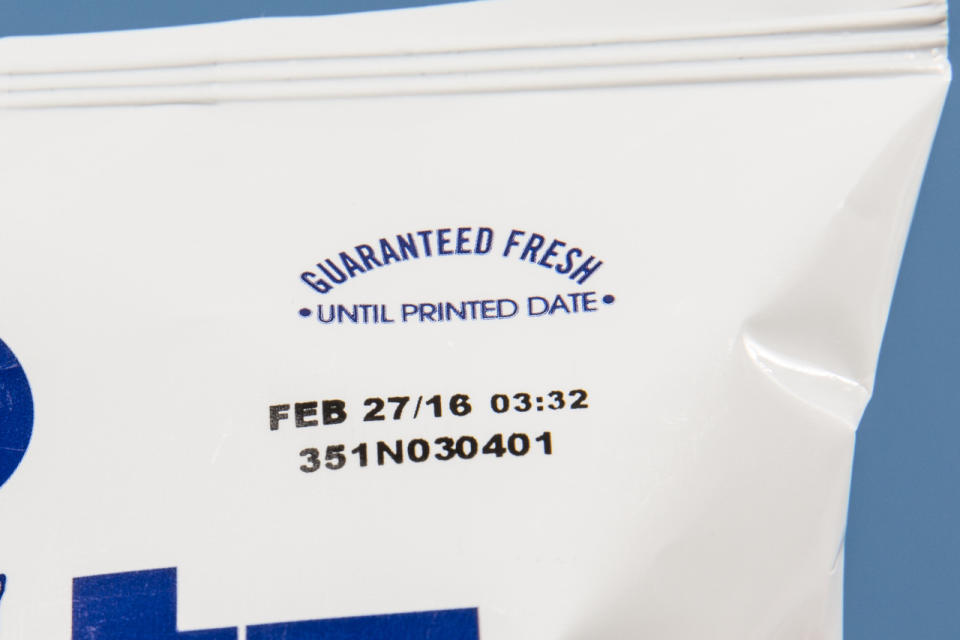

Expiration dates signify freshness and taste

…and not some mystical time where your food will “expire.” But “freshness” in this case is a nebulous, unspecific parameter.

Once dates on packaging became industry standard, the government began to pursue a uniform system for marking freshness dates. There was zero federal regulation and standardization of dates placed on food. The FDA even attempted to gain some control, but since the labels focused on freshness rather than health, they determined it was not worth their precious time.

Despite these murky details, so many of us believe the dates on our food are ironclad parameters that tell us when our food is safe to consume. Except for my Aunt Linda, who consistently fed me expired yogurt whenever I visit her. As it turns out, she may have the right idea.

Most food companies come to their freshness conclusions by conducting taste tests (yes, seriously)

According to 99% Invisible, a group of testers will subjectively sample food of varying ages and then take a survey. Those results lead to the freshness (or “expiration,” or “best by”) date. So some random tester saying “these waffles taste kind of weird” determines that seemingly concrete but actually very non-scientific expiration date on your food and drink.

And smaller companies, without the budget/time for a taste testing session, will sometimes just estimate (read: make up) their dates. So, if your artisanal, small batch, locally sourced chipotle-infused pickles still taste good a few weeks after they “expire,” it’s no coincidence.

More: Myths You Shouldn’t Believe About Breakfast

Credit: Flickr/Chris Waits

The words and phrases food companies use are ridiculously inconsistent

In what may be the most comprehensive look at this mess, in a joint research paper conducted by the NRDC and the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic, the authors state “…[The inconsistency] exists on multiple levels, including whether manufacturers affix a date label in the first place, how they choose which label category to apply, internal inconsistency within each label category due to the lack of formal legal definitions, and variability surrounding how the date used on a product is determined. The result is that consumers cannot rely on the dates on food to consistently have the same meaning.”

“Expiration date,” “freshness date,” “Best if sold by” – the nomenclature stamped on our food varies from state-to-state. There are no individual definitions for what these phrases mean, and it’s almost as if every state threw a dart at a word cluster and just went with it. There’s no uniform system tying our nation’s food products together, no official metric to judge these dates by, and no government agency overseeing or enforcing this system.

This awful system is all just a marketing scheme

In the late 1970s, it was becoming clear that Americans were drifting away from their natural food sources, and buying the bulk of their eats in supermarkets, in pre-packaged or frozen form. During this boom, most food products had encrypted freshness dates that only retailers could read. But this information wasn’t plainly visible to the public.

In 1977, the New York State’s Consumer Protection Board did their best impression of this guy, and published a booklet “decoding” these retail-only (secret!) codes so the average consumer could gain some “top-secret” insight into their food products.

The public began clamoring for clearly stated codes on packaging, so they didn’t have to buy some stupid booklet, and food suppliers delivered. These expiration/freshness/best-if-sold-by dates were birthed and shelved in your local supermarkets, and have largely remained the same.

More: 10 Types of Seafood You Really Shouldn’t Eat (and 10 You Should)

Credit: Cole Saladino/Thrillist

We waste money, food, time, and more food due to a basic lack of understanding

In 99% Invisible, they profiled a Montana supermarket manager who was forced to throw away “100s of gallons of milk” every week, because Montana’s laws don’t allow the sale or donation of food 12 days past its expiration date (for reference, they claim the industry standard is 21 days). This not only amounts to a baby-pool of spilled milk every week, but also makes the price of milk in Montana about $2 more expensive than nearby states.

And according to the aforementioned study, “At the consumer level, according to one calculation, food waste costs the average American family of four $1365-2275 per year.” This is about 160 billion pounds of waste, by the way.

Can we do anything to fix this horrible mess we’ve made for ourselves?

Some guy who invented the Atari or something once said the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results.” That’s pretty much what we’ve been doing with the dates on our food for more than four wasteful decades.

The NRDC and Harvard paper lays out a few options to help educate and curb the problem of consumer’s misunderstanding what dates mean for them. They call for all “sell-by” dates to be invisible to consumers. The authors of the paper also propose a uniform system of marking, and (most importantly, in my book) creating substitutions like “freeze by” dates to help people understand the shelf life of their food, and how to keep it the freshest.

Until then, we can our part by educating ourselves using reliable, entertaining, and informative sources on food, and life in general.

Oh, hey… kind of like this one.

More from Thrillist:

55 Restaurants That Give You Free Food on Your Birthday

Chain Restaurant Workers Reveal What You Should Never Order

Critical Food & Drink to Have in Your House in Case of Emergencies