The time to rescue your old videotapes is right now

Every time I walked by my videotapes drawer, I heard their silent screams.

“Why did you record us if you’re never going to look at us?” they seemed to cry out. “Don’t you know we’re magnetic tapes? Don’t you know we have about a 10-year shelf life? Even now, as you ignore us, we’re degrading! Degraaaaaaadingggggg…..!”

We all know that audio tapes, camcorder tapes and VHS tapes are old, analog recordings — and that with temperature and humidity changes, they begin to deteriorate after about a decade. The only alternative to oblivion is to transfer them to a digital format before they’re completely corrupted.

But who’s got the time for that? That’s either (A) very labor-intensive (if you do it yourself) or (B) very expensive (if you hire a company to do it for you). Most of us, therefore, do option C: Nothing. Torn by indecision, we just let them rot.

I finally decided I couldn’t let that happen. I had to act while there was still time. This is my story.

The Challenge

I am that guy: the one who used to bring the camcorder on every vacation, who audio recorded every rehearsal and performance. (I spent 10 years working on Broadway shows as a conductor and arranger.)

Nowadays, everything I shoot is, of course, digital. But until phone cameras and digital cameras came along, I amassed boxes and boxes of tapes.

To be precise: 157 VHS tapes, 83 audio cassettes, 34 Hi-8 camcorder videotapes.

Lots of companies offer to transfer old tapes like these. Some are small and local. Some are national, or even international, operations. But choosing one is incredibly difficult, because you don’t know how well or how safely they’ll convert your tapes until you get them back. Nobody can compare the companies’ work, because nobody would ever bother digitizing a huge tape collection several times to see which batch comes out best.

So I decided to do the conversion-company research up front, choose just one outfit, and then let you know how it went.

I’m fortunate enough to have a well-informed sounding board for this kind of thing: my followers on Twitter.

I asked if any of them had had any good experiences with a digitizing company. In their replies, three names came up over and over again: Costco, YesVideo and Southtree.

As it turns out, YesVideo and Costo (and Walmart and CVS) are the same thing. (YesVideo “white labels” — secretly does the work — for those other chains.)

Southtree does its own work out of a 40,000 square-foot production facility in downtown Chattanooga, Tennessee. They have over 1,000 playback machines. I liked what I read on its site.

I began corresponding with Southtree founder Nick Macco to find out what I was in for. “How similar are all of the conversion companies?” I asked him.

“Most of us use very similar equipment,” he wrote back. “We source and repair the best of old tape players. We have a dedicated staff who repairs and maintains all this equipment; they know based on experience which players provide the best playback and reliability.”

He pointed out that you you have to transfer analog tapes in real time; to digitize a one-hour video, it takes one hour. That’s what makes this kind of project so daunting for do-it-yourselfers.

“We’ve created custom workstations that let our technicians manage multiple capture and digitizing devices simultaneously,” he told me.

Southtree says it cleans or repairs your tapes as necessary, and may try each tape on different players to get the best signal out of it.

Finally, Nick suggested that I sign up for Southtree’s email newsletter, which offers frequent discounts as high as 50% off. I did. (If you don’t want to wait, you can use the code YAHOO to get 40 percent off.)

With a 50-percent discount code, my final bill for the 275 tapes was about $2,000.

My only disappointment in the pricing was that Southtree charges by the tape, even if there’s very little on it. Many of my old VHS tapes had just a three-minute recorded portion (an interview, usually); did I really have to pay a full-tape price just for that?

“We like to keep it simple with just a flat rate,” Nick told me. “Some places charge by length, but we find it easier for us and the customer to just charge per item converted.”

So I packed up the tapes, sent them to Tennessee and waited.

Direct to drive

What’s really odd is that Southtree, YesVideo and other competitors seem hell-bent on converting your old tapes to DVDs. Like, what? Why would you want to convert one outgoing, obsolete format into another? I don’t even have a DVD player in the house anymore!

What I wanted, of course, was for all of the video to be put onto a hard drive or flash drive, but none of that is available on Southtree’s price list (or YesVideo’s).

Nick assured me, though, that they do offer this service. If that’s what you want, you sign up for the DVD conversion and then type something like, “copy to the drive I’ve supplied” in your order notes. That’s what I did (I mailed them an old hard drive), but it seems odd that these companies don’t more prominently offer direct-to-drive services. Even Nick acknowledges that 30% of his customers ask for this arrangement, and says that the site will soon be updated to make the offerings clearer.

Anyway, the work didn’t take long. In under a week, I had big boxes shipped back to me: The originals, plus a huge set of neatly labeled DVDs. (Southtree swears that I didn’t get special rush treatment; that’s really how fast they operate.)

And, of course, the real gem: my hard drive, now full of sequentially numbered audio and video folders.

What I got

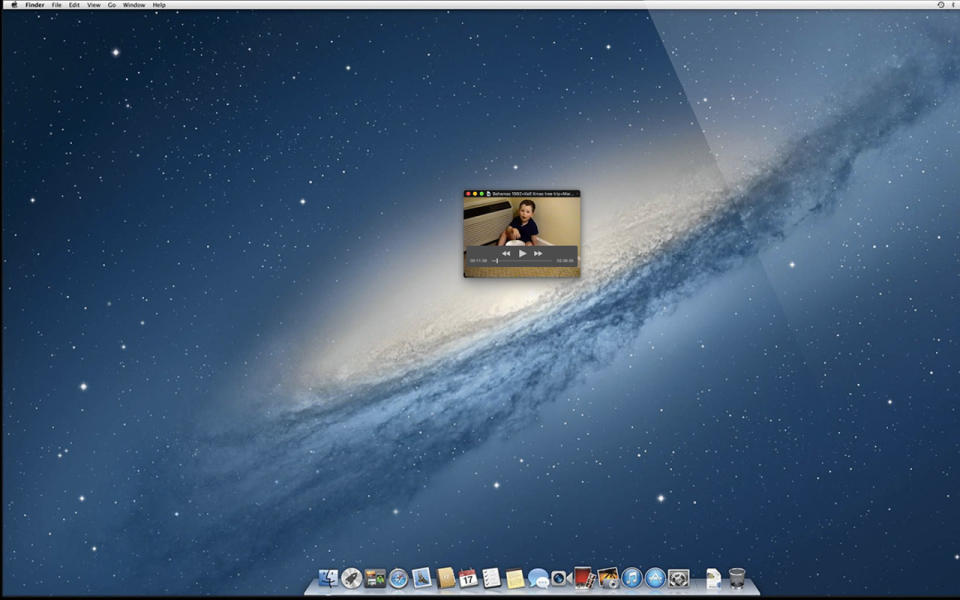

I plugged the drive in and started double-clicking. The first thing I noticed was that the videos are tiny! For a quick second, I wondered if something had gone wrong; why was the video playback window the size of a Triscuit?

Then, of course, it hit me: A VHS video is only 333 x 480 pixels! Even MiniDV camcorder video, which is digital, is only 640 x 480 pixels. Here’s what a VHS tape looks like at full resolution on a 15-inch laptop screen (2880 x 1800 pixels):

Suddenly, I really appreciated the invention of high-definition video.

You can, of course, make your playback window bigger. That blows up your ancient, blurry video and makes it blurrier yet, but it’s not bad.

That was my entrance down the rabbit hole. For days, I sat, watching amazing blasts from my past, footage and events long forgotten. One video had no sound; a handful flashed a VCR error about cleaning or calibration during the opening seconds.

Otherwise, though, the conversions looked amazing.

Suddenly I was revisiting Christmases from 30 years ago, when all four of my grandparents were alive and present. There were video postcards from long-lost loves. There were school plays.

There were also some real gems. Like the time my sister and I took our grandfather, then 104 years old, on a trip through southern Ohio, and happened to spot then-governor George Voinovich …

There were ancient TV appearances, in which I reviewed long-forgotten, hilariously crude tech products …

I found my firstborn child’s first steps (he’s now a sophomore in college) …

And most eyebrow-raisingly of all, I found the oldest existing video with sound of my younger self: A local Cleveland TV news story from 1979, when I was 16 years old, commenting about our school system’s decision to ban Christmas and Hanukkah carols:

Sorry about the hair.

What it meant

When they were younger, my kids were always uninterested in my recording videos, let alone in watching them. If I wanted to, I could make an entire montage of elementary-school Pogues saying variations of, “Dad, turn that off!” to the camera.

Now, though, they’re teenagers, and things have changed. For the last couple of weeks, I’ve been entertaining them with footage of their younger selves —scenes that none of us even knew existed. Scenes that unleash memories, people and locations they’ve long forgotten — or that they haven’t forgotten, but can now compare against their mental recordings.

When I’ve found old clips of friends, family and colleagues, I’ve posted them to YouTube with private links. Their interest is immediate and joyous. Sure, maybe only 5% of this video stash is worth posting and showing. But at least, in digital form, that 5% is simple to edit, title and post.

A digital video file is better than a videotape in the same way that a digital photo is better than a 35mm slide in a box in the basement: It’s instantly accessible. The much shorter path to seeing that footage — that lack of friction — makes all the difference in the world. It’s the difference between seeing and enjoying those memories and slowly forgetting about them.

(One friction point that often goes unmentioned: Even if you did load an old tape into an old player and connect it to an old TV, you still didn’t have random access. You couldn’t click around in the video, or fast forward at 16X, or quickly snip out the boring shots. You were trapped in Linear Land.)

Now, I can already imagine the comments that will pile up below this column. “Get your face out from behind the camera and start being in the moment, dude,” they’ll say. “Too bad you’re so hung up on the past that you can’t enjoy the present!”

Sure, whatever. All I know is that my video memories are now safe from oblivion. They’re mine to play, show, and post whenever I like. They’re a time machine that lets me view a 25-year stretch of my life — how I was, how my kids were, how my family and friends were. I’ve learned what parts of our personality have changed with age, and which were essential and unchanging. I’ve observed how styles in haircuts and clothing have come and gone — not just in society, but in us.

If you never bothered to record the big and small events of your life, I’m sorry. But if you walk by your cabinet full of tapes each day and try to block out their silent screams, here’s my advice: Listen to them. Pull them out and get them digitized. Otherwise, the tapes, the machines that play them, and the memories they represent will disappear forever.

David Pogue is the founder of Yahoo Tech; here’s how to get his columns by email. On the Web, he’s davidpogue.com. On Twitter, he’s @pogue. On email, he’s poguester@yahoo.com. He welcomes non-toxic comments in the Comments below.