The Strava social exercise app can reveal your home address

A new report claims that the activity-tracking social network Strava — already knocked off stride when it was revealed that its users were unwittingly mapping out secret U.S. military bases overseas — has a major privacy problem: it can publicly reveal where its users live.

To make matters worse, the report from the mobile-security firm Wandera says this problem occurs when users try to mark their homes or other sensitive spots as private, not because of any failure to enable the right privacy settings.

In fewer words, people who followed the company’s advice about how to keep their home addresses private may have instead made them easier to find.

A Venn diagram of risk

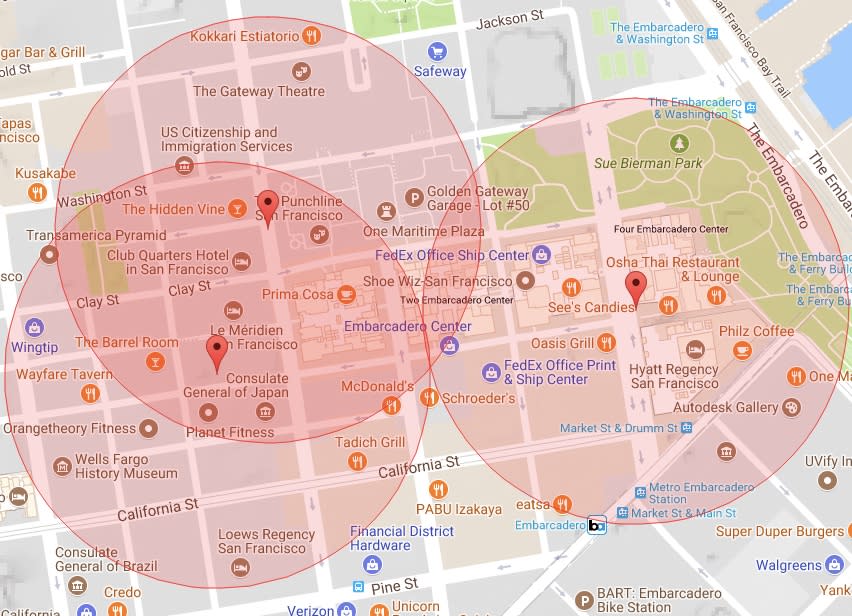

The post by Wandera, one of a new crop of firms specializing in mobile security, explains how Strava’s “Privacy Zones” feature can pinpoint a runner or cyclist because these zones are represented as identical circles of on a map. The circles then block out where you start or end a run.

(Warning, geometry ahead.)

“Using the ending points of an activity, it is possible to determine which radius option was selected by the user and then to triangulate the exact location of the selected address,” the report says. “As the privacy zone is of equal size in each activity, it’s possible to represent this graphically by increasing the radius of circles around each activity end marker until three or more circles intersect.”

Think of the Venn diagrams that have become their own internet meme, except that in this case they let other people know where you live, or at least where you keep your expensive, carbon-fiber road bicycle.

“The re-identification strategy discussed here (points on a circle) appears to be effective and quite problematic,” said Stacey Gray, policy counsel with the Future of Privacy Forum, a Washington D.C.-based think tank. “It might be unique to Strava … I’m not aware of any other fitness app that allows similar radius-based zones of privacy.”

Strava’s sole comment on privacy issues after the military-bases story broke — along with the subsequent documentation by developer Steve Loughran of how to track a stranger on Strava by uploading a fake activity-route log — had been a January 29 open letter posted on Strava’s site by CEO James Quarles.

The post says the San Francisco-based company is “reviewing features that were originally designed for athlete motivation and inspiration to ensure they cannot be compromised by people with bad intent” and is working on “simplifying our privacy and safety features.”

But on Wednesday, Strava spokesman Andrew Vontz addressed Wandera’s report specifically. “While Strava’s engineering team has been working to augment and improve privacy options well before we were contacted by this company and others, we appreciate their interest in our platform,” he said. “In the coming weeks Strava will be rolling out more privacy options for users.”

What Strava could do instead

Wandera has ideas of its own about how to fix this problem.

“Strava should look at randomizing the distance that their privacy zone uses for each activity so that the radius can’t be used to determine the exact hidden location,” wrote Dan Cuddeford, director of systems engineering, in an email forwarded by a publicist.

For example, he said, Tinder suffered from the same issue until Include Security documented how the dating app’s implementation of a location feature could help an attacker pinpoint a Tinder user’s location to within 100 feet.

“Tinder has since updated the app and now it only shows a rounded distance rather than a precise distance,” Cuddeford said.

Cuddeford added that Wandera offered this recommendation to Strava when it disclosed this research to the company last year. Wandera says Strava’s response was more or less, the “privacy zones were working as intended and users could opt-out entirely if required.”

He had some counterintuitive advice for Strava users — Wandera employees are among them — to use the app more privately: Turn off privacy zones. Instead, he recommended an analog implementation of a privacy zone: “Don’t start/stop Strava activities until you are a random distance from your sensitive location.”

Strava’s other usability problem

Wandera, however, skips over another usability failing with Strava: To use Privacy Zones at all, you have to set aside the mobile app in which you’d otherwise exclusively interact with the service and instead go to its web site.

Gray — after noting that Strava’s privacy options overall seem “to be at or above the industry norms in most respects”—did not approve of that omission. Nor did she endorse Strava’s app not giving users a way to opt out of having their activity aggregated into the heatmap.

But, she added, even if an app puts privacy-protecting options in plain sight, that doesn’t mean its users will stop to consider and use them: “Most consumers do not understand this aspect of data practices of apps that collect location.”

Related Video:

Watch original series, sports, and more on go90.

Email Rob at rob@robpegoraro.com; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.