Neil deGrasse Tyson: How the Webb Telescope Lets Us See ‘Ghosts’ of the Past

In the third installment of Pop Mech Explains the Universe with Neil deGrasse Tyson, we explore how the James Webb Space Telescope gives humanity a window into the deep past, helping us see familiar parts of our universe in a novel way.

New episodes in our multi-part video series will debut every Wednesday, so be sure to check back for more of Tyson’s thoughts on the multiverse, aliens, and the greatest scientific achievement of 2022 (so far). And if you missed the first two videos, check out our episodes on Tyson’s start as an astrophysicist and why he says we’re not living in special times.

A Telescope That Exceeds All Expectations

When fully expanded, Webb’s largest feature, a sunshield, is about 72 feet by 40 feet. It was designed to fold 12 times so it could fit within the Ariane 5 rocket on its way to L2, a Lagrange point where it can maintain a gravitationally stable orbit with the sun-Earth system.

So it’s not surprising that when it came time to launch Webb to its cosmic parking spot—a million miles from Earth—a ton of components had to function perfectly.

“So much had to go right to deploy this telescope,” Tyson tells Popular Mechanics. “Clever engineers had to figure out a way to furl the telescope, so it fits in the fairing of the rocket, then we sent it the million miles into space; have it deploy heat shields, so that the temperature of the telescope can drop to almost near absolute zero, basically adopting the temperature of space itself,” he explains, because Webb’s detectors need to avoid infrared heat “contamination” from its own instruments.

Everyone rooting for Webb was cautiously optimistic that the entire process would go smoothly. Almost a year after its launch, Webb has proven that its engineering was sound. “Even though the telescope only met the specs, it exceeded all our expectations,” Tyson says.

A Portal to the Past

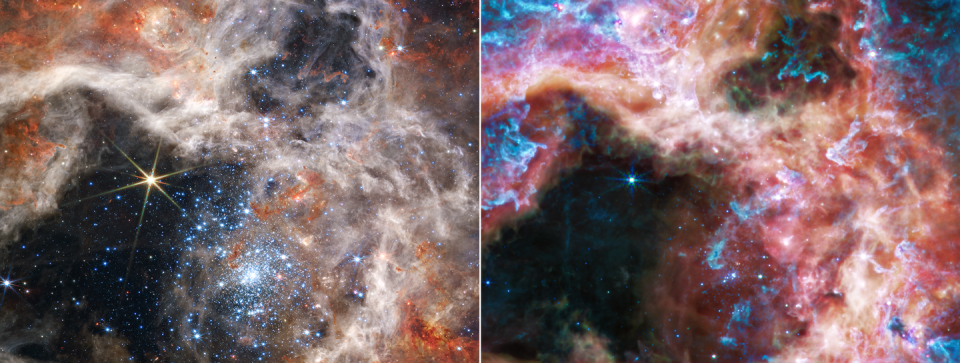

Webb has returned one stunning image of deep space after another from the early universe. The telescope is designed to look for infrared light for a particular reason, Tyson says.

“There was a gap in our telescopic space-time continuum, where nothing on Earth could get high-quality data from that early on in the universe,” he says. That’s because when stars and galaxies are born, they emit ultraviolet light. But as they travel through space that’s been expanding since the Big Bang, the light waves end up stretching into longer wavelengths. “By the time it reaches us, it’s infrared,” Tyson explains. So far, Webb has seen galaxies that formed over 13 billion years ago. It has also given us a new view of planets in our own solar system.

“It’s a portal through which we’ve been transported to a new era of high-resolution, high-quality data in modern astrophysics,” Tyson says.

Ghost Stars?

So how do you wrap your mind around the fact that we’re looking at celestial objects so far in the past? Are they still around if their light took millions or even billions of years to reach us? The speed of light is 299,792,458 meters per second, but the universe is vast.

Tyson provides a great example to illustrate why astrophysicists aren’t too worried about faraway objects existing or not.

“If we were in the same room, and let’s say, you were an arm’s reach from me, I don’t see you as you are. I see you as you once were, three-billionths of a second ago,” he says. But because human beings live for many decades, that time isn’t enough to cause any meaningful change in a person. If one person was on the moon, they’d still only be one-and-a-half seconds away. Put someone on the sun, and they’d be eight minutes away. Once you get out to a nearby star, the person you’re talking to would not see you for maybe 20 years, a significant amount of time in a human life.

“For most stars in our galaxy, the light-travel time is small compared with their life expectancy. So we’re not losing sleep over whether the star whose light we received today is really different from whatever that star actually is doing today,” Tyson says.

Astrophysicists do see stars that have exploded thousands or millions of years ago, using specialized telescopes, he adds. “We speak of them as having exploded in the present, just because it’s easier that way. So it is true that what we see in the night sky are all ghosts of something that may or may not still be there.”

You Might Also Like