Mylan CEO Blamed Obamacare for EpiPen Sticker Shock

The price of the EpiPen has soared 500% since generic drug company Mylan bought the treatment nine years ago. Yet Mylan’s controversial CEO Heather Bresch says she and her company aren’t solely to blame for the fact that patients are paying more for the must-have allergy medication. Another culprit, according to Bresch: President Obama.

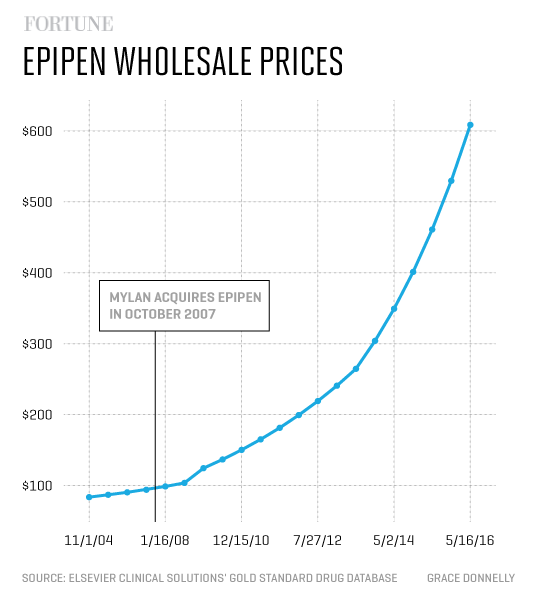

On an earnings call earlier this month, Bresch blamed EpiPen sticker shock in part on Obamacare. She said that employers’ increased use of high-deductible plans, one of the side-effects of the law, has resulted in patients paying more out of pocket for the drug, and that’s “where you’re seeing a lot of noise around EpiPen.” What’s more, Bresch, citing the roughly $600 wholesale cost, added that when you look at other treatments, the EpiPen does not fall into the category of “an expensive product.”

Mylan is no stranger to controversy (see my profile last year, “Why Wall Street Loves to Hate Mylan’s CEO”). But EpiPen, a portable device that counteracts potentially life-threatening allergic reactions known as anaphylaxis, is supposed to be the company’s shining success story. In fact, prior to the recent price hike backlash, Mylan was looking to make the EpiPen more expensive.

The company has been actively trying to renegotiate contracts with pharmacies and distributors this year that kept the EpiPen competitively priced with is biggest competitor, Sanofi’s Auvi-Q. But now that the Sanofi drug is no longer on the market--the company recalled its entire supply last fall, and has since abandoned it--Mylan is looking to ditch contracts that constrained EpiPen’s price. “I think you’ll see opportunities for us to continue to have that price per pen increase,” CEO Bresch said at a conference in May.

Mylan, already the most dominant maker of epinephrine auto-injectors, now enjoys a near-monopoly on the market since Auvi-Q’s withdrawal: After the recall, EpiPen’s market share immediately jumped from 85% to 95% at the end of last year. That lead remains safe at least into 2017, after an attempt by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries to release a generic version failed to pass FDA muster earlier this year. The only other product on the market, the lower-cost Adrenaclick by Impax Laboratories , has recently grown from 2% market share to 7%, but it’s still only considered interchangeable with EpiPen in 21 states, according to a research note Wednesday from RBC Capital Markets.

Mylan did not return Fortune’s request for comment about the Obamacare connection. But in a statement on Monday, Mylan says it has tried to make EpiPen accessible and affordable to people who really need it, offering rebate cards that allowed 80% of patients with commercial insurance to get the product for free last year.

Still Mylan appears to be learning the same hard lesson this week that Martin Shkreli and Valeant learned last year: Investors love when pharmaceutical companies raise drug prices--until everybody else gets really upset about it. Shares of Mylan have dropped more than 11% this week, down more than 5% on Wednesday alone.

And the EpiPen controversy is drawing comments from some high-profile figures, including Hillary Clinton and Martin Shkreli himself, who tweeted that he thought the EpiPen’s price should even be higher. On Wednesday, Clinton said there was no justification for the price hikes. Her comments came shortly after the Senate Committee on Aging asked Mylan to provide information on the reasoning behind what it called the “drastic” price increase of EpiPen, and the American Medical Association “urge[d]” Mylan to “rein in these exorbitant costs.”

The pricing scandal is happening at the worst possible time for Mylan. This is typically the company’s biggest season, driven by EpiPen sales, which peak during back-to-school shopping as parents and schools equip for the coming year.

And EpiPen is a huge point of pride for Mylan as well as for Bresch herself. Inside Mylan, executives including Bresch all refer to EpiPen as her “baby”: It’s Mylan’s first billion-dollar drug, reaching $1 billion in annual sales in 2014 and 2015--making it what the pharmaceutical industry calls a “blockbuster.” That’s an even rarer feat for a generic drug maker such as Mylan, which makes most of its revenue not on brand-name drugs, but on cheaper, equivalent versions of other companies’ branded medications.

When Mylan acquired EpiPen as part of a transaction with in 2007, the drug had already been on the market for about 25 years--its initial approval in the U.S. was way back in 1939--yet it was such a no-name it wasn’t even mentioned in the press release of the $6.7 billion deal. At the time, EpiPen was making less than $250 million in sales. “This was a side show at best,” Bresch told me last year.

Bresch, who at the time was overseeing the Merck integration as president of Mylan (she became CEO in 2012), saw EpiPen as a hidden gem. She poured marketing resources into the product, and embarked on an awareness and political campaign to get more EpiPens into schools and other public institutions. Today, 47 states have laws about making epinephrine auto-injectors available at school in case of an anaphylaxis incident, largely as a result of Bresch’s efforts. Mylan signed on famous spokespeople for EpiPen, including actress Sarah Jessica Parker and celebrity chef Amanda Freitag.

Under Mylan, sales of EpiPen grew at an average annual rate of 33%, more than doubling their 13% annualized growth rate before Bresch took charge. A lot of that growth came from increasing EpiPen prescriptions as the product became more mainstream: In the first seven years Mylan owned EpiPen, the number of patients using it grew 67%, according to Bloomberg.

But price increases also drove sales growth. In the first year Mylan owned EpiPen, its price increased nearly 5%, to about $99 for a set of two EpiPens. But the following year, in 2009, the wholesale acquisition price of EpiPen jumped 26%; since 2012, prices have increased almost 30% each year. In May, Mylan raised the price of EpiPen another 15%, to $608.61 for a pack of two, according to Elsevier Clinical Solutions’ Gold Standard Drug Database. In total, that amounts to a more than six-fold increase in the wholesale price of EpiPen since Mylan bought it.

Still, if anyone is equipped to defend Mylan’s unpopular moves--say, its tax inversion to the Netherlands last year--it’s Bresch. “There's going to be good things that get you and there's going to be bad things that get you, so you better be willing and your skin better be thick,” Bresch told Fortune last year, quoting her father, U.S. Senator Joe Manchin. “I try to look at it from the perspective of I should be flattered that so many people are trying to tear us down.”