The man who wants to replace Merkel and run Europe's biggest economy has one very big problem

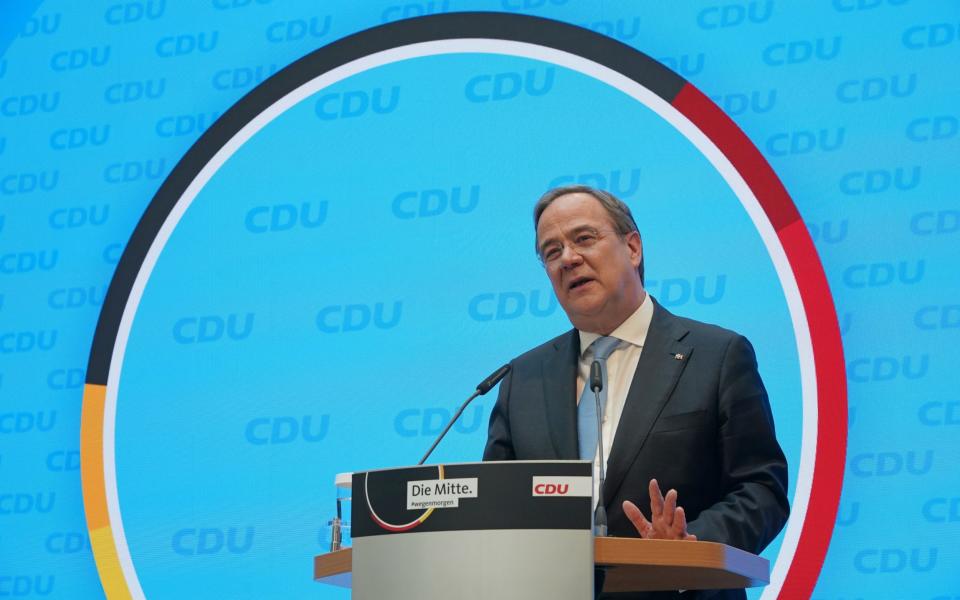

“Puzzling”, “weak” and “unpopular”: Armin Laschet faced a tough reception in Berlin after being confirmed as the Christian Democratic Union’s chancellor candidate on Monday.

After winning the backing of the party’s board - if not the backing of German or CDU voters - Laschet looks set to be thrust into the job of steering Europe's biggest economy and the EU’s post-pandemic recovery.

“It makes it a very close race,” says Carsten Brzeski, chief economist at ING Germany. “With Merkel you had a weakening party but an extremely popular leader. Now you have a weakening party with a weak leader and a not popular leader.”

Economists say the former journalist and son of a miner will be a continuity candidate to carry on Angela Merkel’s legacy of centrist politics after September’s election.

But they warn he could be forced to compromise if a poor performance weakens the ruling CDU’s hand in coalition negotiations. Berlin’s sacred debt rules are in the cross-hairs of likely coalition partners while ripples from fiscal policy tweaks in Germany will reach Brussels.

Christian Odendahl, chief economist at the Centre for European Reform, says: “He's a middle of the road German conservative, but he does have corporatist instincts.”

With Laschet the leader of the heavily industrial state of North Rhine-Westphalia, having “German business interests at heart” is his “instinct”, Odendahl says.

“I could well imagine him to be very pragmatic but we shouldn't expect any centrist radicalism in the way of Joe Biden or something … don't expect any big shifts in German economic policy.”

'Old school' approach

While stepping into the shoes of Merkel is a daunting task for any German politician, Laschet is an intriguing choice to reverse the CDU’s recent poll slump.

“Laschet is old school, old generation, old politics,” says Brzeski. “This is clearly a decision taken by the party top and somehow not to break with the past so a very conservative one.”

The North Rhine-Westphalia leader has dismal approval ratings in his own state, while a survey last week found that just 15pc of Germans and 17pc of CDU/CSU voters believe he is the party’s best chancellor candidate.

By comparison, the far more popular and charismatic Markus Söder, leader of its Bavarian sister party the CSU, was preferred by 72pc of conservative voters. A number of CDU heavy hitters, including economy minister Peter Altmaier, defected to Söder in a bitter battle for control but party grandees had the final say.

“The choice between Söder and Laschet was about style, charisma and perceived electoral appeal rather than major differences on substance," says Holger Schmieding, Berenberg’s chief economist. He adds Laschet’s “somewhat unassuming style and penchant to moderate and bridge differences resembles Merkel’s approach”.

That could be crucial come September when the coalition horse-trading will begin in Berlin. Polls suggest the CDU is still ahead on just under 30pc of the vote but the party has given up almost all the gains made in the early phase of the pandemic.

The stalling vaccine rollout, a PPE procurement scandal and delayed business grants have thrown September’s coalition mathematics up in the air. An unpopular chancellor candidate could worsen the CDU’s recent polling woes, particularly against the well-liked Greens' choice, Annalena Baerbock.

With a record polling rating, the second-placed Greens are likely to play a crucial role in the next government, ending the current “grand coalition” between the CDU and SPD.

Berenberg puts a 60pc chance of a CDU-Green pact but says there is a 35pc chance of Laschet’s party losing power for the first time in 16 years. A “traffic light” coalition between the Greens, SPD and liberals is the most likely pact without the CDU.

How debt could impact race

The Greens’ programme of higher public investment puts it on a collision course with Laschet and the CDU. The defining legacy of Merkel’s fiscal policy is the debt brake - a constitutionally enshrined rule that limits the structural deficit to at a tiny 0.35pc of GDP except in crisis times.

But ultra-prudence in Berlin has been derailed by the pandemic, with support for higher public investment growing in the business community even before Covid struck. With the pandemic breaking Germany’s borrowing taboo, the debt brake, which was brought in after the financial crisis, is under threat.

Christian Schulz, Citi economist, says the conservatives “have long prepared for a coalition with the Greens” and expects any higher investment to be funded by extra borrowing rather than tax hikes.

While some caution that an overhaul of the debt brake may struggle to get the two-thirds majority needed in German parliament, economists say there are also ways around the problem.

“The Greens will definitely push Laschet in the direction of easing the debt rules for climate investments - that’s the Greens’ main goal,” says Odendahl. “This is where Laschet’s corporatist instincts with a green investment agenda could meet, so big investment funds to make sure that German businesses can adapt to the climate challenge.”

A more relaxed attitude to borrowing in Germany is likely to also mean change in Brussels. A self-proclaimed pro-European, Laschet’s residence in Aachen near the border with the Netherlands and Belgium may hint at continued close relations.

EU members have taken a major step towards closer fiscal ties with the Recovery Fund, while Covid has also shined a light on fiscal rules deemed outdated by several members.

Schulz says a “watering down of EU fiscal rules might still be more feasible than under previous German governments” but adds the Greens will have to “scale back their European ambitions” in government.

Many believe that heavily indebted countries, such as Spain, Italy and Greece, have little hope of meeting the 60pc to GDP public debt target and 3pc deficit aim under the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact.

With interest rates kept at low levels, an overhaul of the rules will be debated by EU countries after being suspended to help them provide huge Covid support. Support in Berlin for a relaxation would be crucial to getting an agreement.

On Tuesday Söder admitted “the die is cast” as he conceded in the bruising race that has enveloped the party in recent weeks.

After four successive election victories, the CDU opted for continuity over charisma. But in backing Laschet, many believe the party is gambling its grip on power.