How watching videos online could get more annoying under Donald Trump

American voters don’t get a direct choice in who runs the Federal Communications Commission, but the FCC exercises an outsized influence over the gadgets and services they use. The regulations it writes and enforces—and the telecom mergers it blesses or tries to block—open and close vast possibilities for the companies that connect us.

For example, in the alternate universe where President Obama lost in 2008, an FCC (and a Department of Justice) led by John McCain appointees might have okayed AT&T’s 2011 bid to buy T-Mobile (TMUS). With that carrier gone, would AT&T (T), Verizon (VZ), or Sprint (S) have upended the wireless business the way T-Mo has? Would Sprint even have survived for long before being gobbled by Verizon?

The FCC will take a different course once President-elect Trump names commissioners to replace the current majority of Democratic appointees, led by FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler. Their likely first step: clicking the “Undo” button on Obama’s key tech-policy initiatives.

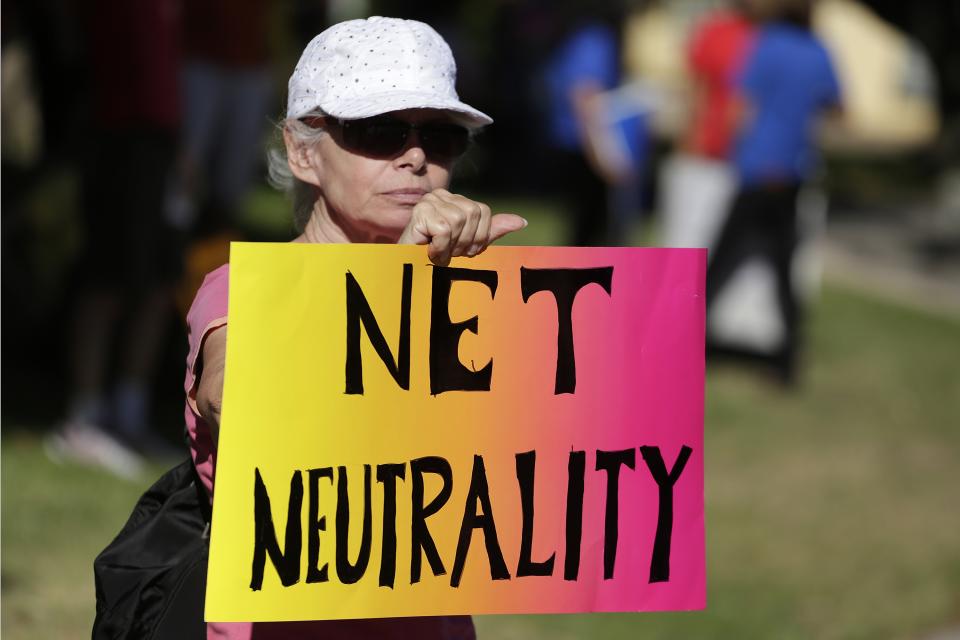

Net neutrality

The net neutrality rules the FCC enacted last year, which bar internet providers from blocking or slowing sites, services and apps or charging them for better delivery, have become the tech-policy equivalent of the Affordable Care Act—an Enemy No. 1 for conservatives. The net-neutrality regulations may have survived a court challenge, but their odds of surviving much longer are about to get worse.

“My expectation is that Wheeler’s policies will be largely gutted,” e-mailed Hal Singer, a principal at Economists, Inc. and a senior fellow at George Washington University’s Institute for Public Policy.

Will Rinehart, director of technology and innovation policy at the Washington-based, free-market-minded American Action Forum, concurred, saying the net-neutrality rules “will likely be on the chopping block.”

But these rules might not entirely vanish.

Berin Szóka, president of the libertarian-minded group TechFreedom, suggested that a Trump FCC could revert to the much weaker regulations adopted in 2010, which banned wireline providers from blocking sites but allowed wireless providers to block apps if they didn’t compete with their own services.

Or the commission could operate on a case-by-case basis, taking action if it sees evidence of uncompetitive behavior.

The FCC may also take the path of least resistance. “It’s much easier — and less likely to embolden activists — to simply not enforce the rules that exist,” e-mailed Karl Bode, founder of DSL Reports, a site that’s chronicled the broadband business since it consisted of phone-based digital-subscriber-line service.

Harold Feld, vice president at the digital-rights group Public Knowledge, identified one reason to keep some net-neutrality protections: “The broadband industry itself has adjusted by buying content and developing advertising they plan to deliver on each other’s networks.” So, for instance, AT&T will sell its DirecTV Now video service to Comcast and Verizon subscribers.

The Republican-controlled Congress might act, too. Here, net-neutrality advocates may feel some angst over rejecting a 2015 bill that would have put net-neutrality rules into law while blocking the FCC from further regulation of broadband providers.

Said Singer: “Had Wheeler accepted the compromise, it would be much harder for conservatives to repeal.”

Urge to merge

Under Obama, the FCC helped quash such proposed mergers as AT&T’s T-Mobile bid and subsequent maneuvering by Sprint to buy T-Mobile. Candidate Trump suggested he’d stick with that pattern, saying in an October speech that he’d block AT&T’s proposed purchase of Time Warner (TWX) and break up the merged Comcast NBCUniversal (CMCSA).

Don’t count on Trump living up to those pledges.

“I suspect it gets dropped,” Singer said. “He is appointing traditional, Reaganite folks to run the transition. These guys aren’t into antitrust enforcement or regulatory intervention.”

Said Rinehart: “The new administration still has to defer to the expert agencies, and if the past serves as a guide, this deal will go through.”

Feld concurred: “The odds have tilted from ‘possible block’ to ‘more likely with conditions’.”

Szóka, however, said approval—and the severity of any conditions imposed on the merged company—would depend on who Trump picks as FCC chair. Given the apparent level of chaos in Trump’s transition so far, we may have to wait to see who gets the nod.

Since Wall Street analysts already have T-Mobile pegged once again as a takeover target, this is a space we’ll have to keep watching.

Meanwhile, a Trump FCC seems far less interested than the current commission in supporting efforts to build out municipal broadband networks that compete with existing internet providers and extend service into rural areas.

“It looks like the new administration may not have any interest in the munis and co-ops for internet access,” e-mailed Christopher Mitchell, director of community broadband networks at the nonprofit Institute for Local Self-Reliance.

The unknown

The background to all this is the remarkable lack of detail Trump provided about his tech-policy views. Observers are now left to glean hints based on the people Trump has named as advisors and members of his transition team.

Two members of the team associated with tech policy, American Enterprise Institute scholar Jeffrey Eisenach and Rep. Marsha Blackburn (R.-Tenn.), “have a long history of opposing pro-consumer telecom policy at the behest of large providers,” Bode said.

Blackburn has also shown a dubious understanding of technology. Most recently, she suggested that the never-passed Stop Online Piracy Act, or SOPA, would have prevented last month’s denial-of-service attack on a domain-name-service provider that left many sites unreachable.

SOPA was a 2011 bill meant to block copyright infringement by tampering with core internet protocols. It would have let copyright holders force internet providers to make entire domains unreachable without first having to prove anything in court. It also would have criminalized attempts to work around those blocks.

“SOPA” itself seemed a sure thing until voters started paying attention to it and got angry, and the same thing may happen to any attempts to demolish current FCC rules wholesale.

“This is my third transition to a situation where the same party holds the White House and both chambers of of Congress,” Feld said. “My experience is that things rarely go as planned, and that efforts to make major changes in the status quo quickly run into resistance.”

Email Rob at rob@robpegoraro.com; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.