Column: Trump can't reopen U.S. after the virus, but governors can't either — only you and I

President Trump's assertion Monday that he has "ultimate," even "total" authority to dictate the reopening of the U.S. economy raised eyebrows among constitutional scholars and set up a conflict with governors and local officials who have placed their own states and communities on lockdown.

"In the coming weeks, the West Coast will flip the script on COVID-19 — with our states acting in close coordination and collaboration to ensure the virus can never spread wildly in our communities," said Gavin Newsom, Jay Inslee and Kate Brown, respectively the governors of California, Washington and Oregon, in a joint statement Monday. "This effort will be guided by data."

Those governors announced an agreement for a shared reopening of their economies, though they set no time frame. A similar agreement was announced by the governors of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania and Delaware.

There is nothing efficient in letting the unemployment rate rise to double digits. When social distancing ends, millions of employer-employee relationships will have been destroyed, slowing down the recovery.

Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, UC Berkeley

Meanwhile, Republican Gov. Mike DeWine of Ohio, who also has been proactive in shutting down economic activity in his state, warned that reopenings won't happen on Trump's schedule. "Sometimes we all think we’re going to turn a switch and we’re going to be back to normal, and that’s just not going to happen,” he said on MSNBC.

The truth is that Trump doesn't have the legal or practical authority to dictate that restrictions be lifted for workplaces and commercial establishments, but neither do the governors.

The pace of any return to normality will be dictated by you and me — by consumers making their own judgments about when and under what circumstances it will be safe to resume old habits, and business owners running cost-benefit analyses on when a flow of customers will warrant reopening.

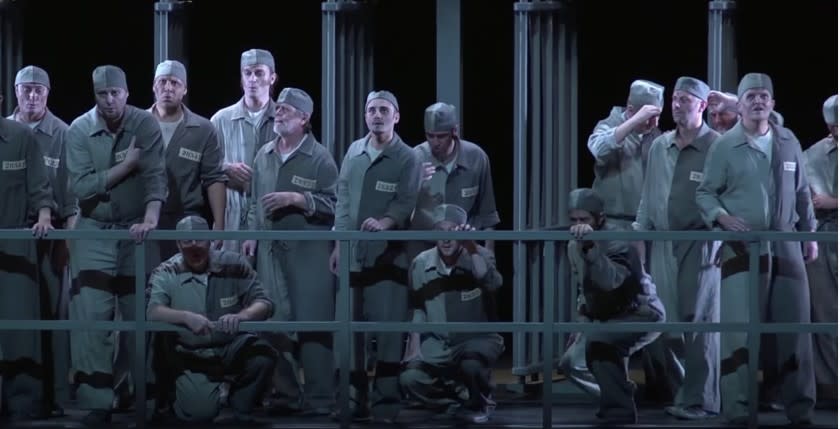

Weeks ago, Trump posited Easter Sunday as the reopening deadline. He seemed to envision the reopening as an uplifting communal moment, perhaps resembling the scene in Beethoven's opera "Fidelio" when the prisoners emerge from their dungeon into the sunlight, the words "Oh what joy, in the open air/Freely to breathe again!" on their lips.

It won't be like that.

For the purpose of creating conflict and confusion, some in the Fake News Media are saying that it is the Governors decision to open up the states, not that of the President of the United States & the Federal Government. Let it be fully understood that this is incorrect....

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 13, 2020

As my colleague Rong-Gong Lin II reported, experts' best guess is that even after the formal restrictions come down, factory supervisors, office managers and consumer businesses will have to factor in new costs. Factories may have to stagger shifts to keep workers at a safe distance from one another. Restaurants and bars will have to accept lower occupancy, which raises expenses.

Then there's the imponderable of consumer behavior. The pandemic has produced more than an economic shock to household budgets. It also has delivered a psychological trauma the depth of which is impossible to gauge.

There's little to go on to determine when Americans might return to pre-virus habits of commerce, entertainment and socializing — when they'll be willing to enter a crowded shopping mall on a whim, stand on a tightly packed checkout line, sit shoulder-to-shoulder with thousands of strangers at a public event, whether amid coughing audience members in a 2,000-seat concert hall or theater or among 40,000 shouting and cheering fans at a ballgame.

The closest thing to a metric we may have is the resumption of air travel after 9/11 — until now, the most abrupt shutdown of U.S. commercial activity in modern memory. Civilian domestic flights were grounded for only two days, Sept. 11 and 12, but the slowdown in business persisted much longer.

U.S. air passenger counts fell from an all-time peak of 65.4 million in August 2001 to only 35.8 million in September. (On a seasonally adjusted basis, passenger counts fell from 59.7 million to 41.7 million in those two months.)

Despite the resumption of flights, passengers remained wary of flying; stricter security arrangements including confiscation of possibly dangerous implements and a slow ramp-up of air marshal coverage contributed to the falloff in flying. Passenger traffic didn't return to pre-9/11 levels until July 2004, nearly three years after the attacks.

Of course that era involved a battle against the discrete, discernable threat of air terrorism. Indeed, outbreaks of passenger panic against travelers who look foreign or Muslim still occur at airports. Concerns about flying now will be centered on the less identifiable risks of contagion, whether from undersanitized planes or contagious fellow passengers. That suggests that resistance to flying could remain deeper or more prolonged. As in many other cases, it's impossible to know in advance.

No matter how well-timed or comprehensive reopening orders are, a return to normal levels of economic activity may happen slower in the U.S. than in other countries. The shutdown underscores not only the limits of governmental authority at all levels, but also the inadequacies of America's approach to employment and healthcare and the holes in its social safety net.

Put simply, if the U.S. had been more caring about the work and healthcare conditions of its rank-and-file workers even before the coronavirus crisis, reopening the economy would happen a lot faster and more easily. That was pointed out two weeks ago, early in the shutdown, by UC Berkeley economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, who are known for their work on economic inequality.

The dramatic spike in unemployment claims seen then (and continued over subsequent weeks), they wrote, "is an American peculiarity." Elsewhere in the world, governments acted proactively to protect employment by covering most of workers' wages through direct payments to employers. "Wages are, in effect, socialized for the duration of the crisis."

In the U.S., by contrast, workers have to lose their jobs first, before becoming eligible for government compensation through unemployment insurance. Unlike in other countries, many aren't guaranteed a job, much less their old jobs, after the crisis passes.

"There is nothing efficient in letting the unemployment rate rise to double digits," they wrote. "When social distancing ends, millions of employer-employee relationships will have been destroyed, slowing down the recovery. In Europe, people will be able to return to work, as if they had been on a long, government-paid leave."

The critique by Saez and Zucman was echoed in a Los Angeles Times op-ed by billionaire philanthropist George Soros and Eric Beinhocker of Oxford. The U.S. government, they wrote, "must immediately guarantee the paychecks of all Americans for the duration of the crisis."

They pointed to such programs in Germany, France, Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, Britain and Australia, all of which are providing direct funding to employers to cover worker paychecks and keep workers in their jobs during the lockdowns.

Similar programs are on the table in Congress. Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) has proposed a “Paycheck Guarantee Act” that would cover wages up to $100,000 per employee as well as healthcare benefits. Without question, this arrangement would hasten the post-virus jobs recovery.

That becomes relevant, however, only after shelter-in-place rules are formally lifted. To avoid a resurgence of infections, healthcare experts say, that can only happen after clear signals have been sounded that the current pandemic is under control. Former Food and Drug Administration commissioners Scott Gottlieb and Mark McClellan, along with several associates, drew a road map at the end of March to guide policymakers.

A state could safely reopen, they proposed, when it had experienced a "sustained reduction in cases for at least 14 days" (the generally accepted incubation period for the novel coronavirus); when its hospitals were able to treat all patients requiring hospitalization without imposing crisis standards of care; when it could test all people with COVID-19 symptoms, and conduct active monitoring of confirmed cases and their contacts.

That's Phase 2 of their four-phase coronavirus response road map. In the words of health insurance expert David Anderson, a colleague of McClellan's at Duke, "Phase 2 requires both massive public health surveillance and the ability and willingness to quickly smother new hot spots of localized infections."

But testing deployment and the equipping of local hospitals with sufficient resources is weeks, if not months, away.

(Phase 3 of the road map is the development of a vaccine or treatments to provide community immunization or measures to limit the severity of infections; Phase 4 is preparation for the next pandemic. We're currently in Phase 1, by the authors' reckoning — suppression of the virus's spread.)

Public health professionals say that thousands of new workers will have to be employed to trace the contacts of infected persons to place them under quarantine.

“We need a Marshall Plan. We need a New Deal. We need a WPA for public health,” Yale epidemiologist Gregg Gonsalves told Kaiser Health News, referring to the Works Progress Administration, which provided thousands of Americans with government jobs on public projects during the New Deal.

That was an era when America was willing to try new ideas and work in concert to extricate itself from an unprecedented catastrophe. We're back in the same fix today, but new ideas aren't getting the same attention or the same broad political support as they did 90 years ago. They must.