The Young Women Who Unknowingly Helped Create the Atomic Bomb

Rosemary Lane’s boss summoned her to his office. It was important, the doctor told her, and the young nurse followed without question. There, a small group of hospital staff gathered around a radio to listen to President Truman address the nation. There was a remarkable new development in the ongoing war, one many felt would end it once and for all. It was a new weapon, and it had just been deployed against Japan.

Rosemary heard Truman describe the power of this bomb, the “battle of the laboratories” and “achievement of scientific brains” that created it, and the countless people across the nation who unknowingly aided in this endeavor. The Secretary of War, Truman added, would soon issue a statement that would “give facts concerning the sites at Oak Ridge near Knoxville, Tennessee, and at Richland, near Pasco, Washington, and at an installation near Santa Fe, New Mexico.”

More from Rolling Stone

Composer: 'Oppenheimer' Score Goes Beyond What's 'Humanly Possible'

Christopher Nolan's 'Oppenheimer' Cast Exits Premiere in Solidarity With SAG-AFTRA Strike

Two words seized Rosemary’s attention: Oak Ridge — her home. Word spread rapidly through the outpost by mouth and media, shockwaves of revelation rippling throughout offices and homes. The secret was out. That secret — the development of the atomic bomb — was kept not only from those who lived outside the secured gates of Oak Ridge, but also from tens of thousands of individuals who served as integral parts of what is now known as the Manhattan Project.

Now, 78 years later, many moviegoers will learn about the Manhattan Project for the first time, primarily from a fascinating yet top-down perspective, via Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. The view of those who “knew.” Physicists and chemists. Geniuses and generals. But their efforts would have amounted to nothing without the female workforce that helped transform their theory into reality.

With legions of American men away fighting, women entered the work world in astonishing numbers and numerous capacities. Oak Ridge employed men and women, young and old, all of whom served as a crucial element in the development of a weapon that would forever change the face of warfare, medicine, international politics, and the environment. Most of these workers had no inkling of their role in this historic event until the first atomic bomb ever used in combat detonated over Hiroshima, Japan. The decision to create and to use the bomb was not theirs. But they would be forever linked to that very choice and its aftermath. Many of them were women. Many of them were still in their teens.

Years ago, I traveled to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, to begin tracking down women and men who had lived and worked there during World War II. I wanted to see this world-altering event through their eyes and unique experiences. At first, they were baffled at my interest. Why would you want to talk to me? I didn’t know anything, was a resounding chorus from many when I initially approached them. But as we spoke, I became enthralled by their viewpoints and inspired by their sense of adventure. They chose to go to a site they knew nothing about, to do jobs that were not fully described to them. They faced uncertainty and secrecy in order to help the war effort and to make a living. In doing so, they helped change the course of history.

Toni Peters, who grew up a few miles down the road in Clinton, watched with her high school friends as a city erupted out of the red Tennessee clay seemingly overnight. More than 50,000 acres that had once been home to a smattering of tight-knit communities were seized by the government claiming eminent domain to vacate the land. Some found notices tacked to trees in the front yard. Others received a knock at the door. The message was clear: move out and be quick about it. Some residents were given as little as two weeks to pack up theirs houses, reap whatever might have ripened in the field and, in some cases, say goodbye to the remains of loved ones who had been laid to rest on properties that had been in their families for generations.

Oak Ridge sprang to life from ground littered with the detritus of uprooted lives. Shoes. Books. Pots, pans, and roaming livestock. Soon there would be little evidence that anyone had ever resided there. Some of those displaced individuals would ultimately end up working for the very project that had evicted them from their homes. By the end of the war, a town that had never existed before 1943, would boast a population of more than 80,000, one of the largest bus systems in the country, and an electric consumption that outpaced New York City. But that city would not appear on a map until well after the war ended.

Though secrecy surrounded the Manhattan Project, its scope and scale made it far from invisible. The herculean construction effort and jobs it provided were impossible to overlook and endlessly intriguing to those who lived nearby.

Purchase Denise Kiernan’s book The Girls of Atomic City: The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II

“Everything’s going in, and nothin’s coming out,” Toni said. At least that’s how it appeared. Train cars and truckloads laden with enough supplies and equipment to not only construct factories and plants, but also to erect an entire town for those who would be working and living there, arrived at the secured site. But for all the materials passing beyond the guarded fence there was no evidence of any resulting product leaving the site. No tanks. No munitions. Nothing. As Oak Ridge grew, so did the mystery surrounding it.

Yet something was leaving Oak Ridge: Uranium 235, the fissionable isotope of the heaviest naturally occurring element on the planet. Vast resources and round-the-clock efforts resulted in a product that could be concealed in a container small enough to be carried in a nondescript bag and handcuffed to the wrist of a courier who would travel with that fuel by train and automobile to a remote outpost in the desert: Los Alamos, New Mexico. (The Hanford site, outside Richland, Washington, focused on plutonium production.)

Recruiting tactics to hire enough workers to keep Oak Ridge running 24-7 varied. Young women like Dot Wilkinson were recruited straight out of the halls of high school. The promise of excellent pay and a guarantee that the work performed would help end the war was enough to convince someone like Dot, who had grown up in rural Tennessee and lost her brother, “Shorty,” to the waters of Pearl Harbor. Economic necessity and wartime patriotism were a powerful and persuasive combination.

Upon arrival, Dot and others found newly razed ground soaked by hot summer rains which resulted in oceans of mud. There were no sidewalks — only boards hastily laid over the pervasive muck. Residents and workers wore security badges indicating which buses they were permitted to ride, which cafeterias they could eat in, and which facilities they were allowed to enter. Women worked in a variety of capacities: Teachers and janitors. Cooks, bus drivers, and telephone operators. And many unknowingly worked enriching the very uranium that would be sent to Los Alamos.

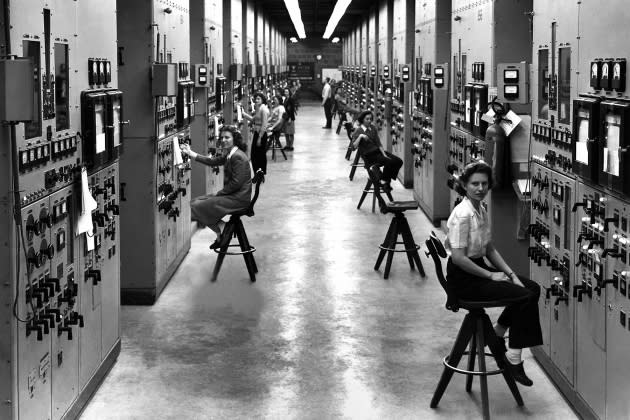

Several processes for enriching uranium were pursued during the war, among them gaseous diffusion and electromagnetic separation. The facility that handled the latter was Y-12. There, Dot and thousands of other young women over the course of the war operated “calutrons,” the key to separating the precious U-235 isotope from the more common U-238.

Day in and day out, Dot sat on a stool watching the panel in front of her. Her training, she said, was fairly simple for this complex and revolutionary piece of scientific machinery: Keep the needle in the center. If it moves too far to the right, turn this knob to the left. If it veers too far to the left, turn this knob to the right. If it sparks, call the supervisor.

Guessing the reason for this massive undertaking was impossible to resist for those who lived inside the gates. But asking too many questions would often result in not only the loss of a job, but also their housing. People talked, and an empty stool or vacant desk soon replaced them. The Project employed what Oak Ridgers called “creeps”— government agents — to spy on residents and visibly enforce security protocols. Women chatting as they hung laundry to dry might get a visit from a creep afterward to inquire about the subject of their discussion. But the government also used the residents of Oak Ridge themselves to help protect the secret they knew next to nothing about.

One evening, shortly after 18-year-old Y-12 worker Helen Brown moved into her dorm, she was summoned outside by two men. Would she mind paying close attention to conversations at work, or in the cafeteria, and make note of anyone who might be a little too curious about what was going on, or anyone discussing what their job entailed? They assured Helen any tales she told would remain anonymous. They handed her forms to fill out and envelopes addressed to the ACME Insurance Company in nearby Knoxville. Helen agreed to keep her eyes and ears open. She was afraid not to. She then hid the papers away in a dresser drawer. She didn’t want to use them.

When they weren’t working, Oak Ridgers found plenty to keep them occupied. The race against the clock meant the city ran 24 hours a day. Worker turnover would slow progress, so the Project established an extensive recreation program to keep folks as content as possible. There were sports teams, clubs of every ilk, bowling alleys, and dances most nights of the week. For some, life in Oak Ridge was what they imagined college might be like, with cafeterias and dorms and dating. For others, like Kattie Strickland, life in Oak Ridge was a very different experience.

A Black woman from Auburn, Alabama, Kattie traveled to Oak Ridge with her husband, Willie, where she would earn more than twice what she could make cleaning the library in Auburn. The pair had been told that Black residents of Oak Ridge were not permitted to bring their children with them, so the children stayed with their grandmother. What Kattie did not know was that she also would not be able to live with her husband. Black women and men lived in separate “hutment” areas. Kattie shared a 16 ft. x 16 ft. room with three other women. No locks on the doors. Limited visitation with their spouses. Curfews and bed checks — often unannounced — ran their lives off hours. Kattie called it “the pen.” She worked as a janitor in K-25, the gaseous diffusion plant, as it was being built. She didn’t know how or when the facility would be used. She collected her pay, parceled it out with Willie, and religiously sent as much as she could home to Alabama.

Even those close to Oak Ridge’s decision-makers remained in the dark. Celia Klemski worked at the “Castle on the Hill” —the administrative headquarters of not only Oak Ridge, but the entire Manhattan Project. Celia often took dictation, sometimes encoded, and once from a general who had the entire office buzzing. No one told her his name, and he said to just call him “G. G.” (Celia later learned that man was Manhattan Project head General Leslie R. Groves, played by Matt Damon in Oppenheimer.) In the same building, women pored over newspapers and magazines to flag words forbidden by the U. S. Office of Censorship. Despite her proximity to those who “knew,” Celia had no idea the reason behind this massive undertaking. She didn’t care. She had a brother in Italy and another headed to the Pacific. She told me she wanted to do her part to help bring them home.

Depending on their education and the nature of their work, there were those who were able to piece together more of Oak Ridge’s purpose. Jane Puckett was a statistician. She dreamed of becoming an engineer, but the University of Tennessee did not permit women in that program. In Oak Ridge, Jane oversaw a room of “computers” — men and women performing calculations that ultimately tracked Y-12’s output. Well into her 80s, she still fumed that male workers beneath her had bigger paychecks.

Virginia Coleman also worked in Y-12. Despite financial challenges and gender bias, she graduated from UNC with a degree in chemistry. A job fair led her to Oak Ridge, where good work and good pay awaited her. In her lab, she and others knew that they were working with uranium — though they were not supposed to utter that word. Virginia knew about fission, and had wondered why, not long after its discovery, that the word and associated research began disappearing from newspapers, magazines, and scientific publications. As August 1945 approached, coworkers in the lab were talking about what was about to happen. About a weapon.

Virginia was taking a much-needed yet short vacation when news of Hiroshima broke. She overheard a group of men discussing the event, marveling that no one in this place called Oak Ridge knew what was happening. Virginia spoke up. “I worked there,” she said. “I knew.”

No one believed her.

Years later, Dot worked as a docent at the science museum. She remembered being approached by a woman who asked how Dot could live with herself knowing that she had helped kill so many people.

She eventually went to Hawaii to visit the closest thing she had to her brother’s gravesite: Pearl Harbor. Looking out over the water, she stood next to a Japanese woman. They were strangers and citizens of formerly warring countries who spoke different languages. Both crying, they turned to embrace each other. What they shared in common were the pain and loss that comes with war.

I will be at the theater the day Oppenheimer opens, but my mind will likely turn to memories of the amazing women I had the privilege to know, all of whom are now gone. These young women and thousands more were part of a generation that straddled two very different worlds: one in which nuclear energy and weaponry did not exist and one in which it could never be ignored. In the former, phrases and words like “nuclear winter” and “fallout” were completely foreign. In the latter, they are frighteningly commonplace. This new world had relied upon the work they performed, impacted by a decision none of them had any part in. They carried that legacy with them until the end of their lives… whether they chose to or not.

Denise Kiernan is the New York Times bestselling author of The Girls of Atomic City: The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II. You can learn more about her work at www.denisekiernan.com.

Best of Rolling Stone