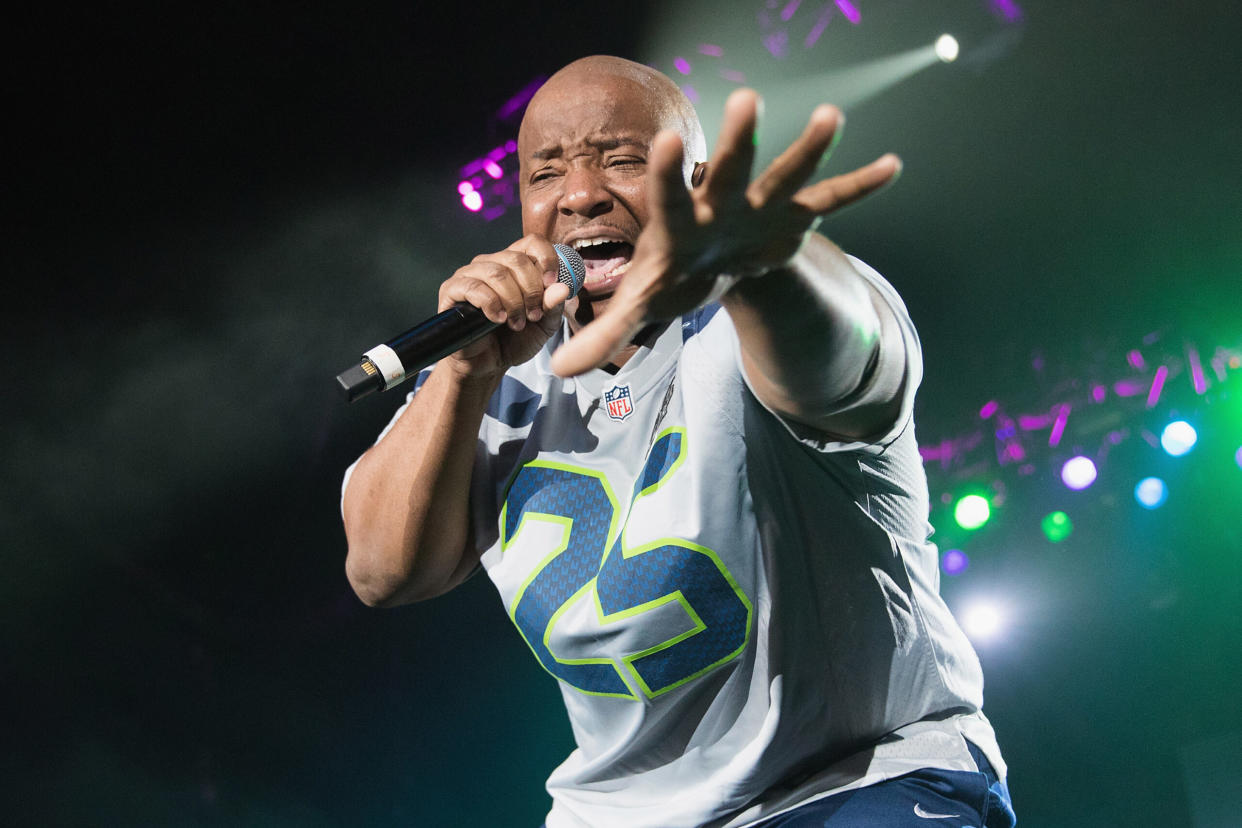

Young MC Tells Us the Story Behind His 1989 Hit ‘Bust A Move’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

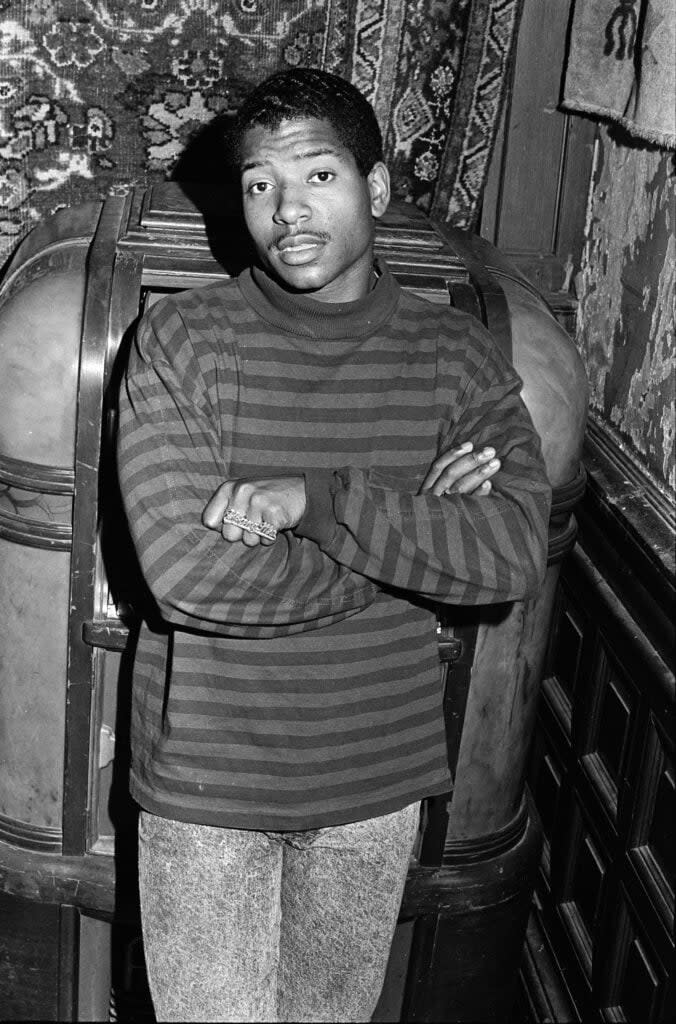

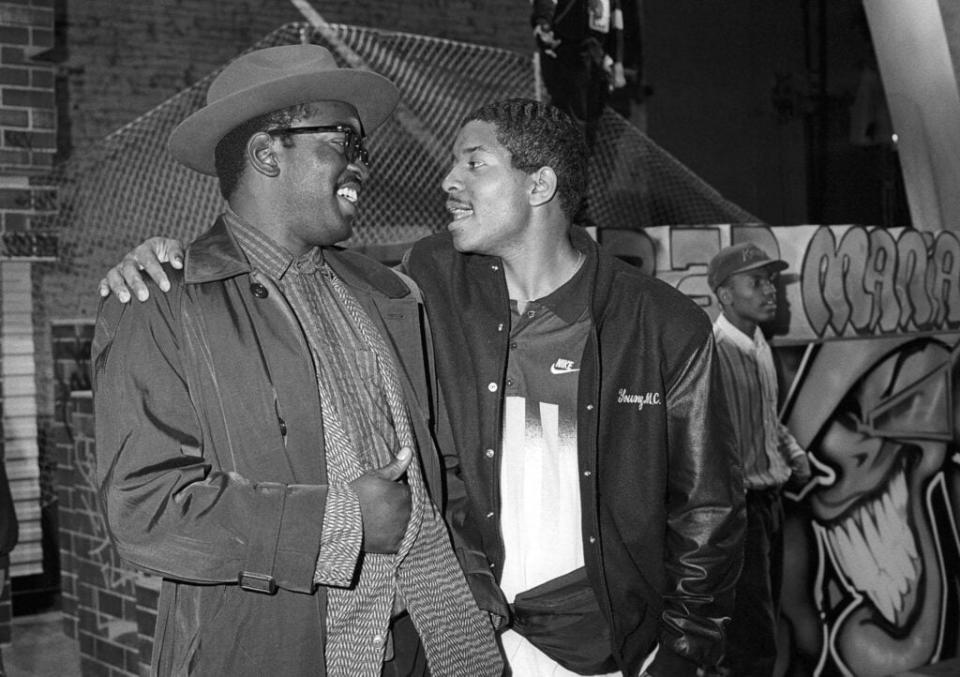

Marvin Young, better known as Young MC, was like a secret weapon for Delicious Vinyl in the late 1980s/early ‘90s. In 1989, he co-wrote the Tone Lōc single “Wild Thing,” which went on to sell more than 2.5 million copies, officially putting the small, L.A.-based label on the map. That same year, Young proved his success wasn’t a fluke when he wrote a second smash for Tone Lōc, “Funky Cold Medina.” Again, the song went platinum and further solidified Young MC’s proclivity for penning hits — at least for other people. When it came to writing his own solo material, he doubted it would crossover into the mainstream. He was wrong.

Less than two months after “Funky Cold Medina” blew up, Young MC exploded from the cannon with his “Bust A Move,” featuring Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Flea on bass and singer Crystal Blake on the hook. Another platinum hit, “Bust A Move” peaked at just No. 7 on the Billboard Hot 100, which, as Young MC explains, had a lot to do with how units were counted back then.

Nevertheless, the song cemented Young MC’s legacy and provided him with the ability to tour well into his 50s. I talked to him about “Bust A Move” and just how risky the song was at the time.

Academia By Day, MC By Night

I was in college at the University of Southern California — this would’ve been 1988 — when I wrote it. And I was writing my songs after homework on school nights. And I remember the draft to “Bust A Move,” once I got the track, took about 90 minutes. Other than changing the title — because it was initially “Make That Move” — other than that, it’s pretty much verbatim.

It’s full-on stream of consciousness, no rhyming dictionary, nothing. And a lot of the big words came from the fact that I was probably doing English or some other homework right beforehand, so my vocabulary’s kind of in that multisyllabic realm. And then I’d write the song.

Shot In The Dark

The sociopolitical climate was a little bit different now than it was then, with basically no internet, not having cable, that kind of thing. You’re not following news as closely if you’re on campus.

But in terms of where hip-hop was, N.W.A. was just coming out. There were a couple things in terms of the West Coast like Ice-T, Toddy Tee, The World Class Wreckin’ Cru, that kind of thing. There wasn’t a lot of crossover in terms of more pop records. So “Wild Thing” had done its thing, but that record hadn’t been broken on K-ROQ. It was broken more on an alternative rock station, and “Bust A Move” sounded more like an R&B track or more of an R&B/dance track, so I had no clue. There wasn’t really anything for me to stand on to say, “OK. ‘Bust A Move’ sounds like this, so I should be able to garner such and such audience.” Some people were comparing it to “It Takes Two” [by Rob Base & DJ E-Z Rock], but the only real similarity was a woman singing the hook. Other than that, they’re pretty different songs.

So a lot of it is somewhat of a shot in the dark because we’re doing stuff that just hasn’t been done. And I tell people all the time, music like that could only happen at that time in California, or at least outside of New York. If I stayed in New York, I never would’ve made a record like “Bust A Move” because it didn’t sound like anything that had been done before. And that was a lot of the focus. When you’re in big hip-hop mecca marketplaces, they want you to do what everything else sounds like. And N.W.A. comes out, there’s not a clamor for everybody to sound like N.W.A.

California Dreamin’

What made it easier to make that song is that nobody was really locked into a sound. There’s more instrumentation from the samples you’re pulling anyhow. Even if it’s drum machine-based, there’s going to be seemingly more live instrumentation, or the feel of it, in terms of making a California hip-hop record as opposed to a New York hip-hop record.

Everybody uses their 808s and things like that, but the music coming out of California at that time was a lot more melodic. That allowed a lot more leeway.

When you’re going through it, you don’t know what’s groundbreaking or not because there’s a ton of records that came out that we all liked that didn’t do as well, that didn’t stand the test of time as much, but they were groundbreaking in their time and from that era. It’s only in hindsight, looking back a few years at least, you get an idea of how big those records were. And then the crossover influence as well.

Delicious Origins

[Delicious Vinyl founders] Mike Ross and Matt Dike sent me the track, and my initial thought for a hook was “make that move.” But it was literally a journey. It wasn’t in first-person, whereas most rap at that point, especially what I was writing, was first-person. Me, me, me, I, I, I… This one starts, “This is a jam for all the fellas.” So I put it in, I guess, third-person.

Rappers can be braggadocious or whatever, but I try to be somewhat truthful. So I’m like, “OK. There’s no reason for me to try and embellish my personal experiences with women at this point. Let me make something that’s identifiable, and let me make something that’s also vulnerable. There were already so many records like the former. I didn’t feel that there was a reason for me to go down that road.

The Crossover

I had extra pressure because, by the time I’m making this, “Wild Thing” is already platinum. People are talking to me, saying, “Why didn’t you do that song?” But I had no intent of doing “Wild Thing.” That was Tone’s — I made it for Tone; I wrote it with Tone’s voice in mind — but having said that, I played a part in a record that was so big, I’m hoping that someone even listens to my song. It’s slower. It’s not rock. It’s more R&B…is it going to cross? It’s got the woman singing in it. It doesn’t have rock guitars in it. “Funky Cold Medina” was breaking around that time as well. So I’m seeing both of those records do what they did with the sounds that they had, and my record sounded so much different, and it was slower. I’m like, “Uh-oh. Hopefully something can happen here.”

Surprise! It’s A Hit

You’re talking about not only a new genre in terms of rap but crossover West Coast rap that barely existed. There weren’t a lot of West Coast records that were getting played on national R&B or pop radio at the time. Nothing had come out of California on a pop or dance level, not to that extent. Nothing.

We’re talking ’88 and ’89. When mobile phones are larger than textbooks and not everybody has cable, and there’s not really much in terms of the internet, you don’t know how big the record is other than looking at Billboard charts and that kind of thing. It’s not like you can go to a website, click, and see how many sales you had. Some of the information may have been out there, but they weren’t giving it to me. But on tour, you land in a city and it’s like, “Oh, they know it here. Oh, they know it here. Oh, they sing it back to me here.” Literally it was like that. You couldn’t track a record, so I didn’t know how big the record was until six months to a year after things were really hitting.

Number…7?!

It took a while for it to go platinum, and it never was certified double platinum, or at least not during that time. I look back on it and at the RIAA, even though I know that it’s multi-platinum, they say that it’s only platinum. This is before Soundscan. So records got played on MTV first, then we got record sales, then we got radio — we never had all three at the same time. You’d be sure “Bust A Move” was the No. 1 pop record, but it wasn’t. It topped out at No. 7. Now, post-SoundScan, it would’ve been No. 1 for weeks and weeks and weeks in a row. But at that time, it was the No. 7 record. The one advantage — and I stick by this to this day — it never got shoved down your throat to the point where every video you turn on, you see it, or every radio you turn on, you hear it, and everybody’s buying it. It never got a point where people get sick of it as much. Plus, the fact I have four verses and the big words and all that other stuff, it took a lot to digest the song, and took a lot to memorize the song. That helped me in terms of the longevity of the record.

New York State of Mind

The success of that song led to high expectations. You try and remake that one a couple times. I was also a typical East Coast rapper, talking about myself and using more mid-tempo beats and whatever. Now I had to wonder, “OK. Am I telling more stories? Am I doing more dance stuff? Is it more uptempo, or do all the hooks have to be singing hooks?” It opened up so many possibilities, but then it made it a little more complicated because it opened up so many possibilities [Laughs].

Ultimately, I was just myself. I just made every record like it was my last record.

To Be Or Not To Be

There’s a part of me that says, don’t take everything so seriously, but taking everything so seriously helped me get through it OK.

I always think of the sweater analogy, that if you pull on this one string enough, you don’t have a sweater anymore. You might have a poncho, but you don’t have a sweater. So if you’re saying, “OK. What string could you pull on to make a better sweater?”

What I would tell my younger self is, “Be smart and keep your eyes open.” Which is what I think I did. Obviously, you can go back and say, “I wish I would’ve took this deal, not took that deal, made this record, cleared that sample, dealt with this company.” But having said that, if I made that one decision, I might’ve messed up two other good decisions that I did make.

Tonsil Trouble

Two days ago, I’m in Los Angeles and the new KDAY is playing. I’m driving up La Brea, and “Bust A Move” comes on. One, I was shocked because I was under the impression that the new KDAY was playing more street stuff and they weren’t playing as much crossover. When I heard it and [Coolio’s] “Gangsta’s Paradise,” I was really pleasantly surprised. And then I really sat and dissected it and listened to it almost like the first time again. I was amazed at how husky my voice was, but I had my tonsils taken out within a year or so of making that record.

Here’s what happened: I made the record, was touring around ’89 or ‘90, did something in Canada where it was below freezing and then immediately flew to Tucson. So I went from humid, freezing Canada, to dry, hot Tucson, and my tonsils gave out. I had to have them taken out. From then on, you won’t hear my voice sounding as husky.

A Red Hot Chili Pepper

If I remember correctly, the video felt big-budget to me because we shot it over two days. So that was massive, that it wasn’t just a few hours total. We actually were in a studio, had all those different setups, a lot of little stuff. It was me in the front, like a Rod Sterling kind of thing, with The Twilight Zone playing over my shoulder.

We had Lou from Soul Train, Max Perlich from Gleaming The Cube, and then Lisa Ann, who’d done some acting. There were some major people in there. Of course, Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers, a major local L.A. band at the time.

It’s kind of wild because I didn’t see Flea. I wasn’t in the studio when that happened. But Matt and Mike hired him, making the track. I think [for the video] they may have shot him either on a different day or different time. If you see the video, he’s outside — it’s a lot brighter when his stuff is shot than when I’m outside. I could have been either inside doing something else, or that may have been another time of day, but I don’t remember even meeting him at the shoot.

They paid him a little session fee. Literally, the track was delivered to me the way it sounded. I have nothing but respect for Flea.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.

The post Young MC Tells Us the Story Behind His 1989 Hit ‘Bust A Move’ appeared first on SPIN.