"Yes’s double and triple albums were seldom off my turntable!" Thomas Dolby opens up on his love of prog rock!

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

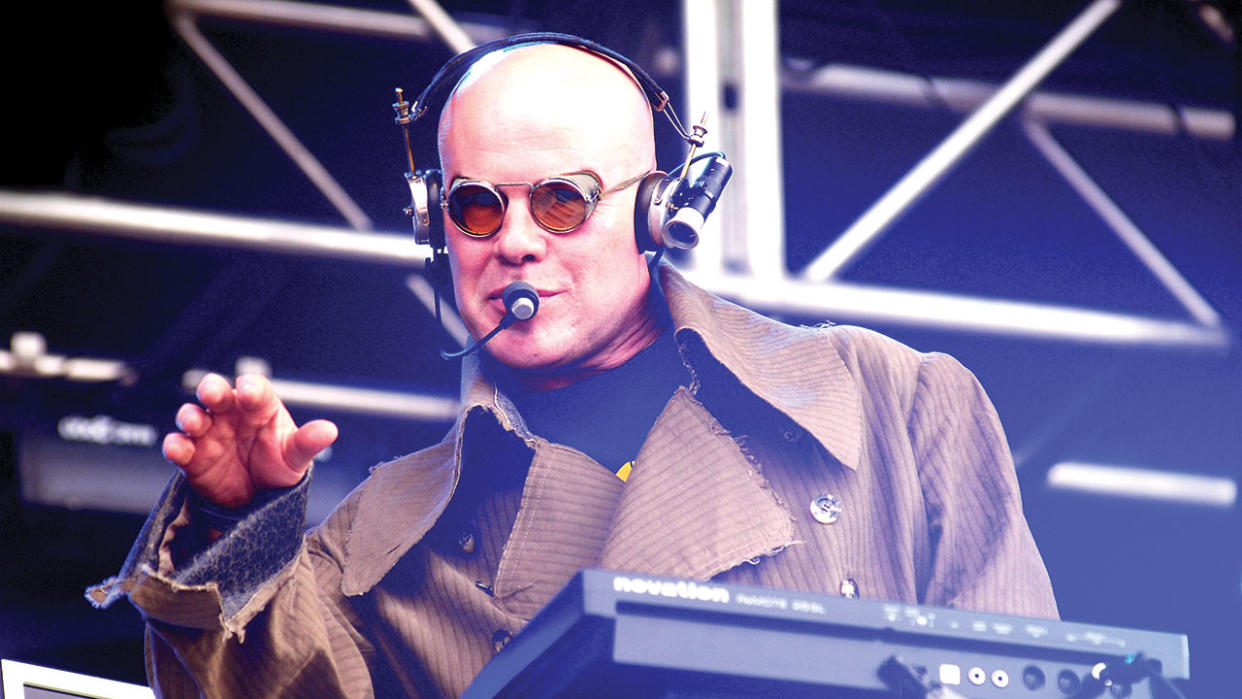

As part of our Outer Limits feature, which discussed the progressive merits of artists on the fringe's of the genre but popular with many prog fans, we sat down with Thomas Dolby back in 2013 to discuss his prog credentials.

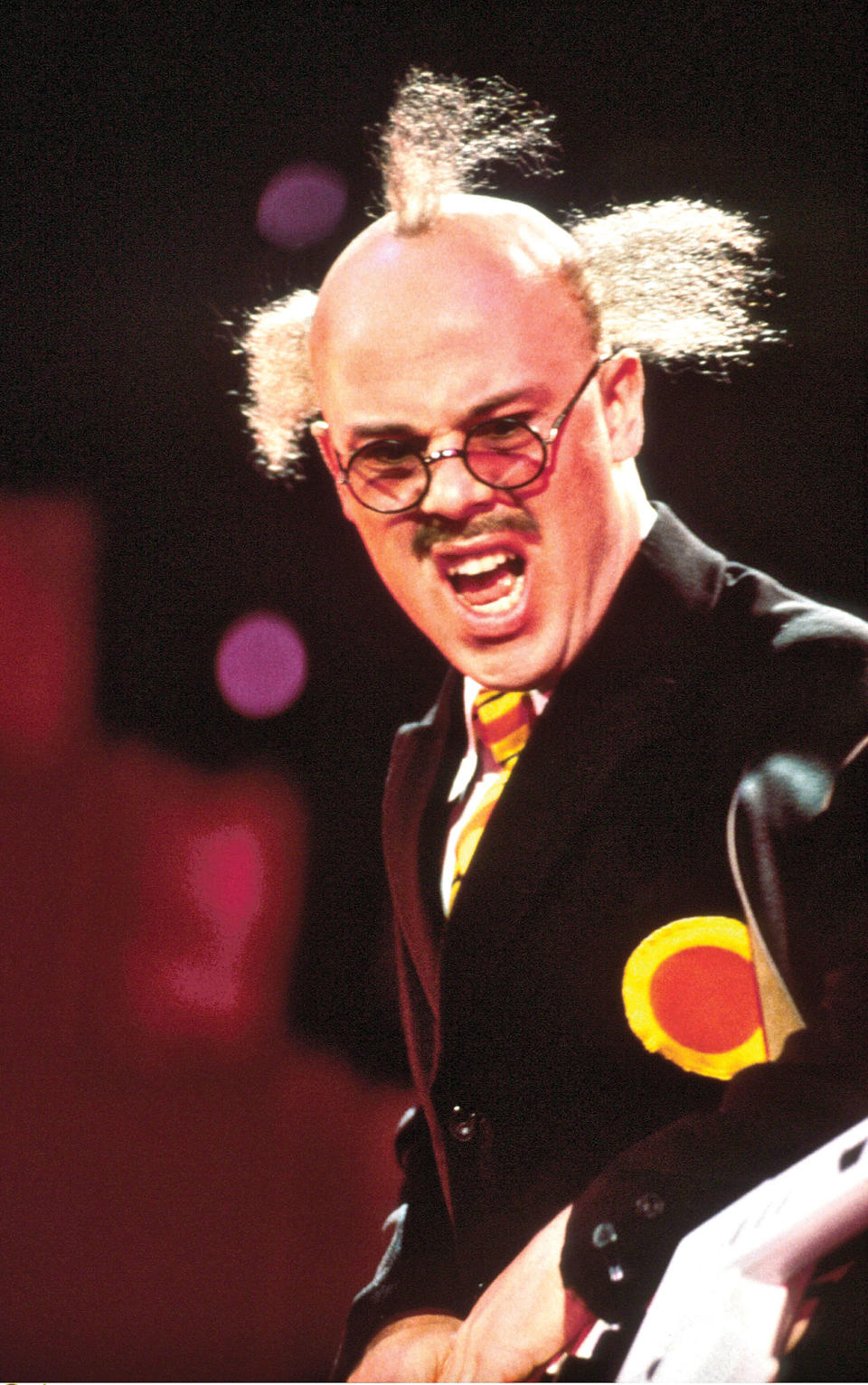

“I remember seeing She Blinded Me With Science, the song Thomas Dolby did with Magnus Pyke – who in the early 80s was the definitive TV ‘mad scientist’ white-haired boffin – on telly when I was about 10,” recalls Steve Jefferis of Warm Digits, those north-eastern purveyors of kosmische electronica and technoid prog. “It was like the Open University had suddenly opened a portal onto the stage of Top Of The Pops, and now seems like a great example of the plain weirdness that passed for mainstream pop when we were kids. It was as if the BBC Radiophonic Workshop had suddenly got the funk, or Cabaret Voltaire had gone slapstick. That faintly comedic element certainly helped it burrow into our brains at that impressionable age, and now looks like a very ahead-of-its-time version of steampunk.”

Having performed onstage with Roger Waters and collaborated with numerous musicians who have skirted the outer limits of prog, such as Andy Partridge, David Bowie and Peter Gabriel, it’s not that weird to find Thomas Dolby in these pages. Then again, having written a seminal early hip-hop track (Magic’s Wand for Whodini), he could just as easily be written about in a rap magazine. Or because of his 80s synthpop hits such as …Science and Hyperactive!, he could appear in a journal forensically examining the history of electronica.

“I was surprised to find myself in some hip-hop hall of fame the other day,” remarks Dolby from his home in Suffolk, in a house overlooking the North Sea. He has his own solar- and wind-powered recording studio moored in his back garden – ‘moored’ because, before it was converted, it saw active service as a lifeboat. With its miniature turret, the house next door resembles a tiny castle. According to Dolby, Brian Eno was going to move in at one point. Prog ventures that his daring, spacious production for Prefab Sprout on their second, third and fourth albums echoed Eno’s radical transformation of Talking Heads on the three albums following their debut.

“That’s an interesting way to see it,” he says, flattered. “I really admire Eno as a producer and artist. He’s the Leonardo da Vinci of modern music. Leonardo who, of course, painted the Mona Lisa as well as invented the helicopter – and the drum machine.”

Dolby is referring to the Renaissance polymath’s mechanical rhythm prototype. “Eno performed similar feats but he never compromised his instrumental work, which has been so influential over the years.”

Like Eno – and Gabriel and, for that matter, Todd Rundgren – Dolby is virtually synonymous with eclecticism and electronic experimentation, with gadgetry and whizkiddery.

“Peter Gabriel is one of the few people in the world I would happily change places with,” he admits. “He’s a wonderful writer and singer. He’s always been single-minded, making albums under his own steam despite pressure from the business to churn out product more often. And he’s always been fashionable without being a slave to fashion – all admirable qualities. Plus, we share an excitement for new technology and the possibilities they open up.”

He cites as an example his acquisition of a Fairlight, that early digital sampling synthesizer, back when, he estimates, only Gabriel, Trevor Horn and Kate Bush owned one. It cost about a third of the price of the flat in Hammersmith, West London, that he bought the same year. “By modern standards it would be worth about a million and a half quid,” he says with a shudder.

Still, you can’t put a price on innovation, a feeling he shares with Rundgren, who he met a few times in the early 90s during a lengthy hiatus from the music business, when he chose to ride the dotcom wave as, among other things, the head of a company designing ringtones for mobile phones.

“We brushed up a few times in the cyber-tech years when Silicon Valley was starting to get arty,” he recalls. “Both Todd and myself were pioneering in the area of multimedia and CD-ROMs so we followed parallel courses.

“I’m proud to be a cult like Todd,” he adds. “When I was growing up, my favourite artists were the cult ones. You didn’t care how many records they sold or whether they were on the radio. You just pored over their double gatefold sleeves for hours. People like Captain Beefheart and Dan Hicks were precious. In a way, it would have spoilt it if they’d gone into the charts.”

Dolby wasn’t born with the surname of the famous noise-reduction laboratory. Before he acquired the nickname that would help afford him a reputation as a computer-pop geek, he was known as Thomas Robertson. The son of an eminent professor of classical Greek art and archeology at Oxford University, he went to Oxford’s Abingdon School and then Westminster School, where he became friends with future Pogues frontman Shane MacGowan.

“We’d sit in coffee bars and discuss music,” he recalls. “Shane was a music guru – he had an encyclopaedic knowledge. I remember him coming in one day and saying, ‘Led Zep and the Stones – it’s all rubbish, dead dinosaur music.’ He said we should be listening to New York Dolls, MC5 and Iggy Pop instead. This was just before punk.”

Dolby had started buying records back in 1972: his first acquisitions were Elton John’s Honky Château and Joni Mitchell’s Blue. Soon he was exploring prog’s topographic oceans. “I was really into Soft Machine, Genesis and Yes,” he says. “Yes’s double and triple albums were seldom off my turntable. It wasn’t the virtuosity that appealed, it was their approach to composition. When I listened to Close To The Edge, what interested me was the way a rock band could come up with different textures, chord sequences and arrangements. They were getting away from the blues and traditional rock figures, and I found that really stimulating. The freedom to change key or tempo was very exciting.”

He was soon trying out these techniques himself after he became the keyboard player for “the best band in school” with his newly acquired Wurlitzer electric piano. His next purchase was a Transcendent 2000 synth that he bought based on an ad describing it as “a poor man’s VCS3, as used by Pink Floyd”.

“Obviously, Dark Side Of The Moon was a hugely influential album at that time, and I thought, ‘I want that!’ The Keith Emersons, Rick Wakemans and Joe Zawinuls weren’t really what interested me. For a start, I never had the patience and discipline to practise scales; I was much more interested in texture, in simple melodic lines, not pyrotechnics. I liked Chick Corea’s solo synth work: he was the first keyboardist to copy techniques from guitarists and horn players.”

Dolby has always considered himself an outsider. Despite his hit singles and the fame they brought him in the mid-80s – he would hang out with Michael Jackson (Dolby originally wrote Hyperactive! with Jacko in mind) and performed at Live Aid with Bowie – Dolby feels as though he has been “on the margins for most of my life”. The one time he felt truly at the centre of things was during punk.

“I was working in a fruit and veg shop and was living in a bedsit,” he remembers, somewhat contradicting the idea of him as the scion of wealth and privilege, the middle-class electro-boffin scorned by the NME. “I had spiky, dyed hair and torn trousers and would go to see The Clash or The Sex Pistols.”

If he was energised by punk, it was seeing Gary Numan that encouraged him to try his hand as a solo electronicist, and hearing Kraftwerk and The Human League that made him realise electronics could be used to create succinct, melodic songs. But it was the prog bands that opened his eyes to the possibilities of the recording studio.

“They were the first to sit in multitrack studios with time on their hands, record company money and an endless supply of psychedelic drugs,” he chuckles. “They were the first to say that a rock band doesn’t have to sound like a rock band; that you can create worlds within worlds and use the studio as a place to dream – and have the headache later on of how to play it live!”

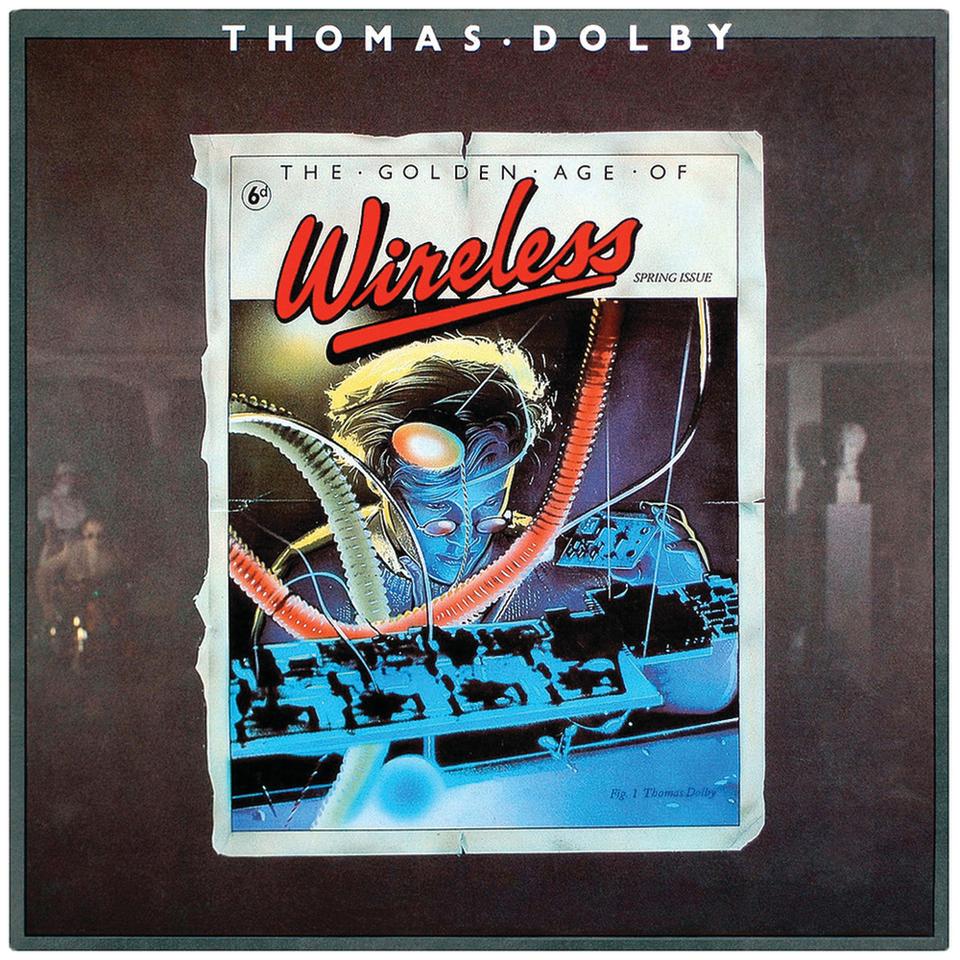

Between 1980, when he played his first solo gig, and the release of his debut album The Golden Age Of Wireless in 1982, Dolby had played keyboards with Bruce Woolley And The Camera Club, toured with and written a hit single for new-wave kook Lene Lovich, written Magic’s Wand, and added synth parts to albums by Thompson Twins, Robyn Hitchcock and Foreigner. That iconic opening keyboard figure to Waiting For A Girl Like You? That was Dolby.

By the mid-80s, he was the Zelig of pop: producing Prefab Sprout’s Steve McQueen, and working with his heroes Joni Mitchell, George Clinton and Bowie. He was also releasing albums that earned him acclaim in the States but saw him denigrated at home, hence his move to LA in 1986.

“MTV made me a very recognisable figure over there,” he explains. “They were like, “How do we get aboard the Thomas Dolby bandwagon?’ Whereas I found the UK very hostile. They didn’t like me because I was clever, white and middle class. Not surprisingly, I moved to where I was wanted.”

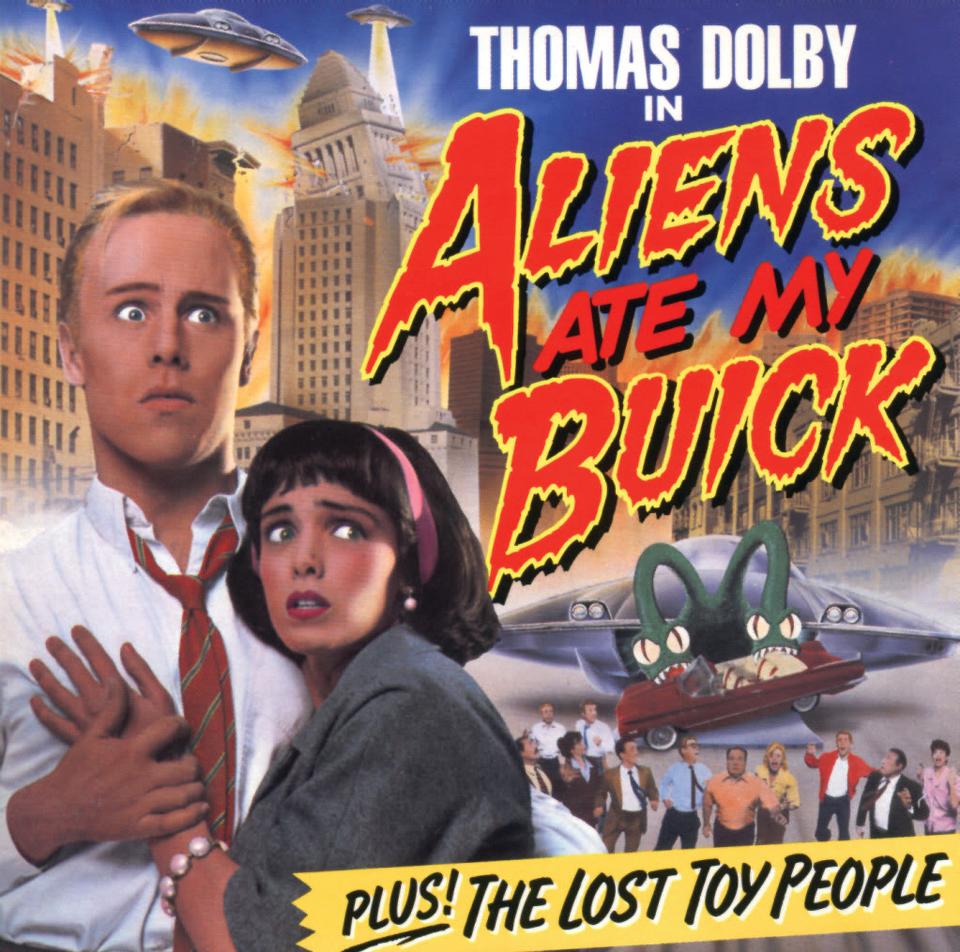

The American press were less suspicious of Dolby’s eclecticism. His debut album has long been regarded as a synthpop classic, while 1984’s The Flat Earth managed to combine prog keyboards with electrofunk to superb effect. He describes 1988’s Aliens Ate My Buick as “a postcard home, like, ‘Hey, mum, I’m having a great time, wish you were here!’”

Shineback mainman and co-founder of Tinyfish Simon Godfrey remembers this album well. “Aliens Ate My Buick was a game changer for me. It made me realise that taking yourself too seriously – especially in prog – is ridiculous,” he says. “Dolby also taught me two of the most important lessons of my life. First: never be afraid to cross the divide between genres if it makes the music better, and second: enjoy your hair while it’s there.”

The new decade began with an invitation to appear as The Teacher in Roger Waters’ production of The Wall in Berlin. “It was an amazing honour because I’d loved Pink Floyd since my early teens and had no idea he [Waters] would have been aware of me,” he says, even though he found The Wall “a dreary piece of music, except for Comfortably Numb”.

Following his production of Prefab’s 1990 epic Jordan: The Comeback and the release of his fourth solo album, Astronauts & Heretics – his “most searching album” – in 1992, Dolby sensed it was time for something completely different. So he headed for Silicon Valley where he spent 12 years living in “a dotcom bubble”. It was, he says, with some relief that he returned to music in the mid-00s.

He also came back to live in England. It was a move that informed his fifth album, 2011’s A Map Of The Floating City, a tripartite concept album with themes ranging from his transgender daughter (now son) to the imminent ecological apocalypse. The album was accompanied by a web-based social networking game designed with the assistance of JJ Abrams.

And now there’s the Invisible Lighthouse tour of Britain’s old cinemas, designed to focus awareness on the Suffolk lighthouse whose beam Dolby used to watch as a child and which was switched off in June. The gigs will feature Dolby behind his computer-ware, backed by a video he made of the lighthouse, of the “eerie, flat landscape” of East Anglia, and of the unexplained UFO sightings in nearby Rendlesham.

“I’ve always liked a challenge,” says Dolby. “It forces me to dig deep and not do something formulaic.”

Pondering his position as the occasional pop star with the experimental impulse, he adds: “I’m not really a party animal. I’m basically an introvert with a very thin streak of exhibitionism. I can get up there and show off onstage, but afterwards I go back into my shell.”