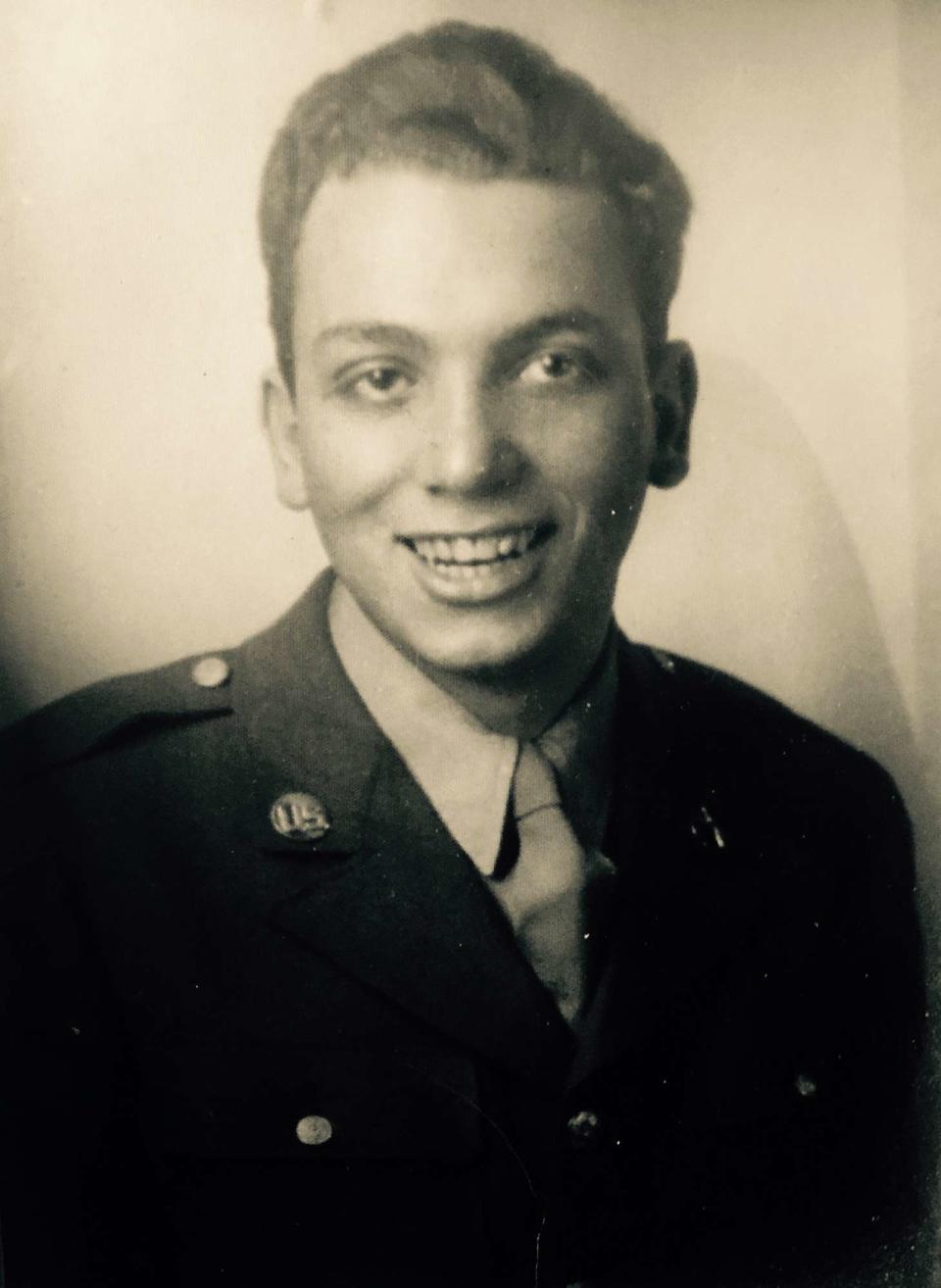

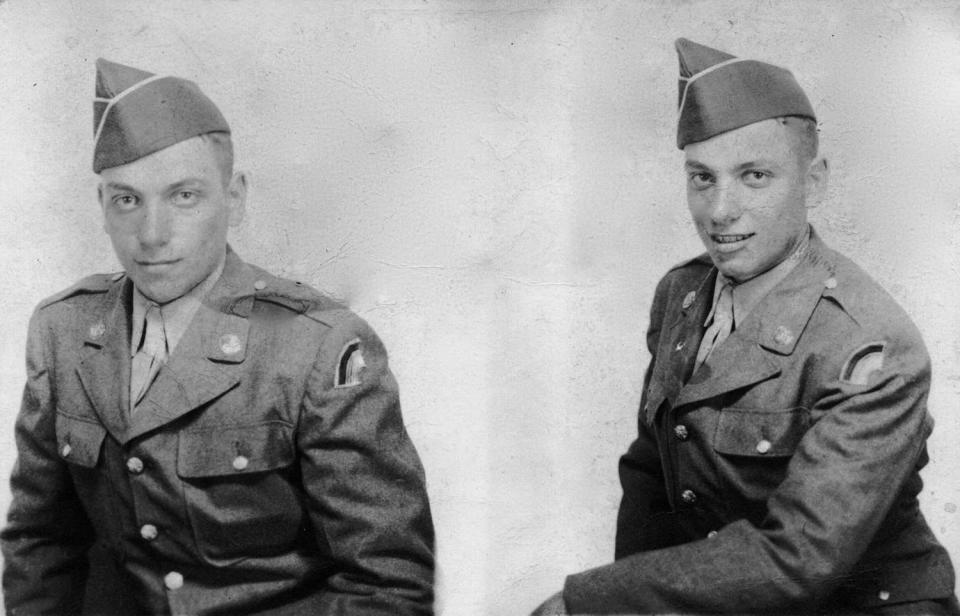

WWII Vet Who Escaped Nazis Finally Gets Purple Heart, Prisoner of War Medal Nearly 80 Years Later

Fred Galloway William Kellerman

For nearly 80 years, World War II veteran and D-Day survivor William "Willie" Kellerman hadn't received official recognition of his sacrifices due to a paperwork error. That changed on Tuesday, when the 97-year-old was presented with a Purple Heart, Bronze Star and Prisoner of War Medal by Gen. James C. McConville, the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, at Fort Hamilton Community Club in Brooklyn, New York.

"I feel like I have been living in a shadow and I've turned the lights on," Kellerman tells PEOPLE. "I will never forget the experience I had back in 1945."

After growing up in the Bronx during the Great Depression, 19-year-old Kellerman ended up on a war ship off the shores of Normandy on June 6, 1944, which became known as D-Day. Within days, he landed on Utah Beach, France, joining the fight against the Nazis.

Just a few weeks later, on July 4, Kellerman's radio was shot while he faced heavy gunfire. With no way to communicate, his captain sent him to find his Battalion's headquarters.

"I said, 'Where do I go?" recalls Kellerman, a private first class at the time, "and he just said, 'Just head that way.'"

United States Army William Kellerman

But as he was jumping through hedgerows and dodging bullets, Kellerman came face-to-face with a German tank and was taken prisoner.

"They came out of the tank with machine guns," says Kellerman, who had to stay with the Nazis in a tent that night. "The next day they took me back where they had about 60 to 70 other Americans that they had gotten."

RELATED: Veterans Return to Normandy on 78th Anniversary of D-Day and Remember Life-Changing Moments of WWII

Kellerman recalls being given one slice of bread a day and only being able to walk at night. "Our planes would shoot anything moving in the daylight," he explains.

United States Army William Kellerman

Thankfully, he managed a daring escape: "I crawled into the bushes, and when they were out of sight, I ran in the opposite direction," he says. "I got to a farmhouse, and it was becoming daylight."

Kellerman says he knocked on the door and tried to explain that he was an American who had escaped, but the residents didn't speak English.

"They gave me all their French clothes and took my uniform and burned it," he recalls.

They wouldn't let him stay because they could all be killed if the Germans found them, so he took off on foot and walked along the railroad tracks, Kellerman recalls.

"Then I got brave," he says of moving from the tracks to the road.

Kellerman felt that he was getting "braver and braver" as he passed the Germans and began to stop at houses for food. After finding a bike along the side of the road and getting a flat tire, he visited what he thought was a bicycle store. But to his surprise, it was actually the secret headquarters of the French Resistance.

United States Army William Kellerman

"It's a good thing I knew who won the World Series that year because they asked me all kinds of questions to make sure I wasn't German," he says. "I convinced them I was who I said I was."

They kept him hidden in the Freteval Forest, where he stayed until Allied forces took over, he recalls.

"I finished the war with them," says Kellerman, who was shot in the leg and hand when he fought alongside Allied forces.

RELATED: On This Holocaust Remembrance Day, Meet a Fierce 100-Year-Old Woman Who Survived the Unimaginable

Kellerman says he recovered at a hospital in Bayreuth, Germany before returning home from the war. He'd go on to attend art school in New York City and live in Havana before settling down with his wife Sandy in Long Island, New York. Together they raised three children as he opened and ran a series of stores offering sewing machines, vacuum cleaners and typewriters.

Jean Kellerman-Powers William Kellerman

He wouldn't return to Normandy until 2018. This time, his family joined him as he received France's Legion of Honor.

"It felt great to be back because they weren't shooting at me," says Kellerman, laughing. "They welcomed me, asked for my autograph and gave me a medal."

But even after that, Kellerman doubted that recognition from his own country would ever come. For years, Kellerman and his daughter, Jean Kellerman-Powers, had been trying to get the U.S. Army to look at his service record, they tell PEOPLE. The 2019 short documentary about D-Day, Sixth of June, finally made it happen.

Filmmaker Henry Roosevelt showed an early cut to Lieutenant Colonel Egan O'Reilly and General Mark Milley (now chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the nation's highest-ranking military officer) and began the process to get Kellerman and other veterans the medals they deserved.

Jean Kellerman-Powers William Kellerman

"The best thing to come out of our film is the audience that watched, listened and acted upon it," says Roosevelt. "That piece of medal and ribbon — one that Willy and his daughter Jeanie have been pushing for decades — that means the world to him and his family. It means that William Kellerman is finally being heard."

Kellerman-Powers adds: "If it wasn't for Henry, this never would have happened."

However, Roosevelt says it "took an army," crediting not only General Milley and Lieutenant Colonel O'Reilly for their efforts, but also Major Grekii Fielder and Captain Jesse R. Ferguson for their endless research into Kellerman's records.

"They came together, cut through the bureaucratic tape and didn't just do the right thing. They didn't do the Democrat or Republican thing. More importantly, they did the human thing," says Roosevelt.

The film also led to Ozzie Fletcher, a 99-year-old Black man who served in WWII, receiving a Purple Heart in June 2021. Fletcher was wounded during the Battle of Normandy, but had been denied the Purple Heart due to racial inequalities.