Writers Praise 2023’s Best Screenplays: 'Saltburn,' 'Maestro' and More

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Every year, Variety asks directors and writers to write about the films that resonated most deeply with them, relating what makes these selected works special, memorable and endearing both to them and audiences overall.

More from Variety

Susanna Moore on Jane Campion's Complex Cowboy in 'Power of the Dog'

Claire van Kampen: Rebecca Hall's 'Passing' Is 'Beautiful, Haunting' Work

Lisa Taddeo on Maggie Gyllenhaal Exploring the 'Inner Life of a Woman' in 'The Lost Daughter'

In the following 13 essays, screenwriters commend their fellow scribes for crafting memorable tales that traverse fantasy and fiction, depict figures both imaginative and historical, and span from Barbieland to New York City.

“P Valley” showrunner Katori Hall describes Marcus Gardley’s dialogue in “The Color Purple” as “both lyrical and cheeky.” Aaron Sorkin commends “Dumb Money” writers Rebecca Angelo and Lauren Schuker Blum for making a witty film about the infamous GameStop short squeeze. And Charli XCX applauds Emerald Fennell for gifting us with some of 2023’s most shocking scenes of the year.

Read on for essays from Guillermo del Toro, Terence Winter, Steve McQueen and more.

All of Us Strangers

Script by Andrew Haigh

Essay by Steve Mc Queen

Andrew Haigh’s profoundly moving adaptation of Mr. Taichi Yamada’s novel “Strangers” is one that, while relocating it decades later to modern-day London, retains the essence of the original ghost story set in Japan, where the lead protagonist — a melancholic screenwriter —revisits his childhood home in the hope of reconnecting with his parents, who are no longer alive. Haigh has made the story truly his own, and through the very specificity he gives to his character Adam’s childhood and adult experiences, he has managed to create something so utterly universal and relatable.

Our past always influences our writing, and Haigh, by interrogating his own past and present, and by definition of that, makes his protagonist a queer man who has a great sense of loss and loneliness. Haigh even returned to his childhood home to shoot, a home that he associates with a time of much sadness in his own life (though his parents are still alive). The searing honesty and vulnerability that Haigh has imbued in his characters leaves an enormous mark on the audience. We go on a journey with Adam; we feel his fears of opening up to his younger queer neighbor Harry; we relish in the gentle intimacy between the two, the new romantic love that is both questioning and caring; when he reconnects with the ghosts of his parents, memories and wounds are reopened yet healed and because of the deep-felt sense of connection, we question the things we wish we had a chance to say to our own parents and loved ones before it was too late.

“All of Us Strangers” is a film about love, both familial and romantic, how love defines us, our relationships and our legacy. This is a script that through its exploration of love makes us reflect on who we are, our loved ones and ultimately, it makes us want to do better in love and at love.

Steve McQueen’s films include “12 Years a Slave,” “Occupied City” and the “Small Axe” trilogy.

American Fiction

Script by Cord Jefferson

Essay by Charles Randolph

I always think satire is like complaining to a stranger, it’s hard to nail the right mix of indignation and generosity.

The complaint in “American Fiction” is a version of James Baldwin’s: Black artists never get to be simply artists, not here anyway — Baldwin’s solution was Paris. Working off the novel “Erasure”, writer and first-time director Cord Jefferson skewers a culture industry reducing Black life to victim narratives, packaging crime as a form of authenticity, terrified and pandering madly. You laugh till you hurt — liberated — and then realize the movie is only just starting to talk to you.

A family drama is a meditation on a mess, yet resolution can lurk too conveniently, just down the reel. Jeffery Wright’s “Monk” is a crank whose family has irretrievably fallen apart.

“American Fiction” is the first theatrical release Wright’s been invited to carry since “Basquiat” (1996 and, What the fuck, people?). He shreds it. His performance allows Jefferson to surprise us with a broader range of both darkness and light than we expect. Two deaths, an estrangement and a dementia diagnosis somehowlead to a wedding, not strictly necessary, and all the more joyous for it. Monk learns his politics are, well, his politics, and that with health bills to pay, few resist their own commodification. The film even invites us to ponder the ending we expect, teases the ending we want, then gives us the ending we deserve.

What Cord Jefferson has done is delineate a problem with one genre and manifest its solution with another, evading the limitations of both. And he reminds us the only way to escape programmatic art, or programmatic ideas, is to muddle our work with humanity.

Charles Randolph’s projects include the Oscar-winning adapted screenplay for “The Big Short,” and writing and producing “Bombshell.”

Barbie

Script by Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach

Essay by Emily Saliers

A day before the movie “Barbie,” written by Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach, premiered in the U.S., I was on vacation in the Faroe Islands, where I desperately snagged the last ticket to see it in the local Torshavn theater. Navigating my way through unfamiliar concession stands and ticketing, I found my seat and sat back, with delirious anticipation, watching the Danish subtitles roll. I had no clue what to expect.

What followed was a fairly thorough exploration of so many of the issues that make this world a hard place: misogyny, patriarchy, sexism, vapid capitalism, aggressive reach for power, and your run-of-the-mill dehumanization.

Add some sugar, please.

Everything in “Barbie” is sparkly fun to look at and good enough to eat: the colors are confectionary dazzling, the pink is oh-so-candy-pink and the roller skates are lime-green fluorescent; this is pop sensibility synesthesia at its finest.

The music and the dancing pulses envelop the audience with infectious disco grooves and heavy bass. It was impossible for me to take my eyes off of Ken, line dancing with perfectly choreographed moves and hand claps to boot, and how could I not feel sheer joy to see the gleam in Barbie’s eyes as she twirls in her perfect Barbie world?

Suddenly, rudely, in the midst of my sonic sugar high, the needle scratches violently across the vinyl, and it all comes to an abrupt stop. The party’s over.

Of course, not really. Because there is a delight in the journey of self-discovery to follow, as “stereotypical” Barbie, appropriately mentored by “weird” Barbie in all her queer wisdom, sets out to discover why she exists.

Watching Barbie is like sucking on a sweetly complex, existential lollipop.

Lest we forget our brothers and the internal loneliness of their male-dominated world, we have Ken to take us through his own journey of discovery and self-worth.

With her remarkably deft touch, director Greta Gerwig playfully and deliciously zooms us through a myriad of scenes: a mother losing touch with her teenage daughter, an absurd corporate board room full of yes-men, an elderly ghost-like motherly figure who touches our childhood hearts, Ken’s confidence fattening as he gorges on real-world patriarchy, a war scene chock-full of flying toy arrows and full fantasy martial arts moves, and a complete breakdown and subsequent reconstruction of a feminist/humanist governing paradigm in Barbie World. Whew. What a ride.

With its brilliant stylization and feast for the senses, “Barbie” dazzled and entertained me to the max. Yet, as I left the theater, I found myself thoughtful and provoked, digging through the complex human struggles and layered issues that lie at the heart of the film. That’s no accident. “Barbie” is an absolute feat of brilliant writing and directing — with a spoonful of sugar to make the medicine go down.

Emily Saliers is half of the Indigo Girls, whose hit “Closer to Fine” is featured prominently in “Barbie.”

The Color Purple

Script by Marcus Gardley, Alice Walker and Marsha Norman

Essay by Katori Hall

Most might have buckled beneath the weight of re-interpreting a classic — a Black one at that. Folks could get their Black card revoked if they didn’t know which character said, “You told Harpo to beat me.” (Sofia if you ain’t know…) There are stories that tattoo themselves on a culture, and “The Color Purple” provoked difficult conversations from bedrooms to barbershops in a community desperate for authentic reflection. It all started with muva Alice Walker in her Pulitzer Prize- winning novel and shape-shifted from movie to musical in the decades since, making Ms. Celie, Mister and Shug ‘nem household names. Now revived as a movie musical in the hands of dramatist Marcus Gardley and director Blitz Bazawule, we can safely say that a classic has not just been revived but multiplied.

Gardley’s pen draws inspiration from Walker’s novel, Steven Spielberg’s 1985 movie and the award-winning Broadway musical (book by Marsha Norman). His literary cap tip is to be appreciated while holding space for his own bespoke brand of unexpected movie magic. Ms. Celie’s interior life is visually articulated on the page in flurries of daring magical realism and given flight by Bazawule’s choice to have cinematography that shimmies and shimmers from the deepest of ebony to the most luminous of pecan mocha tans.

Gardley’s dialogue reigns as both lyrical and cheeky. In a juke joint joust Mister asks Sofia, “Shouldn’t you be at home, tendin’ to your baby?” Her “Shouldn’t you be somewhere with folks yo’ age. Like a cemetery” shuts him up quickfast. That Gardley comeback is every actor’s dream as mouth meets syllables stewed in country confectionary, as sweet to the tongue as it is to the ear. Deadly to the heart in only that it makes it stop for a spell, only to be revived into laughter or searing sorrow. He fears not the sweet silence neither, often using it to pass the baton to the stunning songs of Brenda Russell, Allee Willis and Stephen Bray. It’s why we’re here, to see Black folks falling and flying and to see Celie blow the roof off in ways the novel could never allow. Fantasia’s rendition of “I’m Here” is a classic in itself.

Playwright/screenwriter Katori Hall won a Pulitzer Prize for “The Hot Wing King”; she is showrunner on Starz’s “P-Valley.”

Dumb Money

Script by Rebecca Angelo and Lauren Schuker Blum

Essay by Aaron Sorkin

In the right hands, teaching can be very entertaining. With its screenplay written by Rebecca Angelo and Lauren Schuker Blum, “Dumb Money” was in the right hands. Angelo and Blum, both of whom worked as reporters for the Wall Street Journal before stepping over to the dark side to write screenplays, were perhaps uniquely suited to write the story of how a posse of retail investors took on behemoths of Wall Street. “Dumb Money,” adapted from Ben Mezrich’s book “The Anti-Social Network,” tells the story of the GameStop short squeeze so … they had to tell us what a short squeeze is and then they had to write one like they were writing a bank robbery.

Along the way they teach us about market makers, hedge funds, meme stocks and WallStreetBets and they do it with style and wit and without being at all pedantic. They embrace the music of jargon (and it helps that the musicians include Paul Dano, Shailene Woodley, Anthony Ramos, Seth Rogen, Pete Davidson, America Ferrera, Nick Offerman, Vincent D’Onofrio and Sebastian Stan) and they’re funny as hell.

Angelo and Blum also get us to care about a half-dozen characters who never meet each other. Set during the pandemic when people were feeling isolated and disconnected, when wealth disparity was brought into even greater relief (one character buys the mansion next door to his mansion so he can tear it down and build a tennis court so his family has something to do during the lockdown) they show us why someone would want to be part of a movement.

Given the subject, “Dumb Money” could have easily been mawkish, condescending and boring. Angelo and Blum made it exciting, hilarious and compelling.

Aaron Sorkin’s screenplay credits include “Moneyball,” “Steve Jobs,” “The Social Network” and “Being the Ricardos”

Flora and Son

Script by John Carney

Essay by Andrea Corr

If what lures you to sit and watch a movie is that which lures me more often than not these dark days, it is to be released from the world and ourselves for a couple of stolen hours, to forget our own everyday and be drawn into the lives of others, then “Flora and Son” wonderfully fulfills. “Soothing like a bath,” Flora says of her guitar teacher’s voice. I can only amend this in regard to my feelings on this John Carney film by saying there are surprising bubbles that tickle and the bath water does not go cold. Eve Hewson plays a single mum in working class Dublin to teenage son Max played by Orén Kinlen. He is regularly in trouble with the guards (police). She wants to live a life she didn’t get to live having become a mother to Max at 17 and their relationship is fraught. Both Eve and Orén play their mother/son roles so authentically that they are charming even when they’re swearing at each other. But when they find each other through music, I find my own heart actually squeeze. And I am reminded of John’s earlier films (“Once,” in particular) when I helplessly stop and rewind to rewatch Flora and son make their video (the best day of Max’s life, as he later describes it in a therapy session in juvenile detention). There is a magic to certain musical scenes. This video being one and also the fairy-lit rooftop duet scene between Flora and her guitar teacher/love interest. It is almost like they lift off. It is so quietly seductive this film, heartwarming and funny. A much-needed breather.

Andrea Corr is an Irish singer, songwriter and actor.

The Holdovers

Script by David Hemingson

Essay by Dennis Lehane

The line, “at least pretend to be a human being,” occurs early in David Hemingson’s screenplay “The Holdovers,” and is directed at misanthropic prep school teacher, Paul Hunham (played to perfection by Paul Giamatti). It’s a great zinger, but for me it’s not the defining line of “The Holdovers.” That would be when Mary Lamb (a superb Da’Vine Joy Randolph), the campus cook and another holdover for the Christmas holidays at Barton Academy, tells Hunham, “You can’t even dream a whole dream, can you?” “The Holdovers” is a film about dreams whose minuteness does nothing to minimize their fragility. It’s the story of three castoffs — Hunham, Mary and the student Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa, a terrific actor) — who wander around a snow and ice-chipped New England during the Christmas holidays of 1970, eventually road tripping to Boston for a series of collisions with the ghosts of their respective pasts. In Hemingson’s able hands, it’s an ode to curdled hearts longing to believe — just one final time — in hope.

Dennis Lehane grew up in Boston and has published more than a dozen novels including “Gone, Baby, Gone,” “Mystic River” and Small Mercies.”

Killers of the Flower Moon

Script by Eric Roth, Martin Scorsese and David Grann

Essay by Larissa FastHorse

It’s not easy to write a script for a community you aren’t part of. “Killers of the Flower Moon” depicts a history known to Native American people but less understood by the rest of America. The movie centers around one Osage woman, Mollie Burkhart (Lily Gladstone). Co-writers Eric Roth and Martin Scorsese invited a wide range of Osage voices into their process. However, the movie is primarily from the point of view of the white men who systematically murdered Mollie’s family. Which, to me, is the right perspective for two white writers to tackle. And this is no white savior narrative.

Much can (and has) been said about these writers who represent two lifetimes of incredible work, but one of the most brilliant aspects of this script is the way they depict the villains, William Hale (Robert De Niro) and Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio). It would be tempting to make them arch and clearly evil. But real life is rarely that obvious. Instead, Eric and Martin wrote two complicated men. One did a lot of good for the Native community, including building a ballet school in a nod to my hero, Maria Tallchief. The other was a man who is easily manipulated and seems to think he loves his wife, even as he is killing her.

Outwardly, these characters had Osage friends and family. They spoke the language and worked side by side with them. These men were respected and liked. These characters are relatable to audiences as they look a family in the eye and murder them one by one for oil rights. These men are your neighbor, your boss, the guy next to you at the bar and your lover. That kind of evil, hiding in plain sight, can be the most dangerous and is definitely the harder one to write.

Larissa FastHorse is a 2020 MacArthur Fellow, writer, choreographer and co-founder of Indigenous Direction, a consulting company for Indigenous arts and audiences.

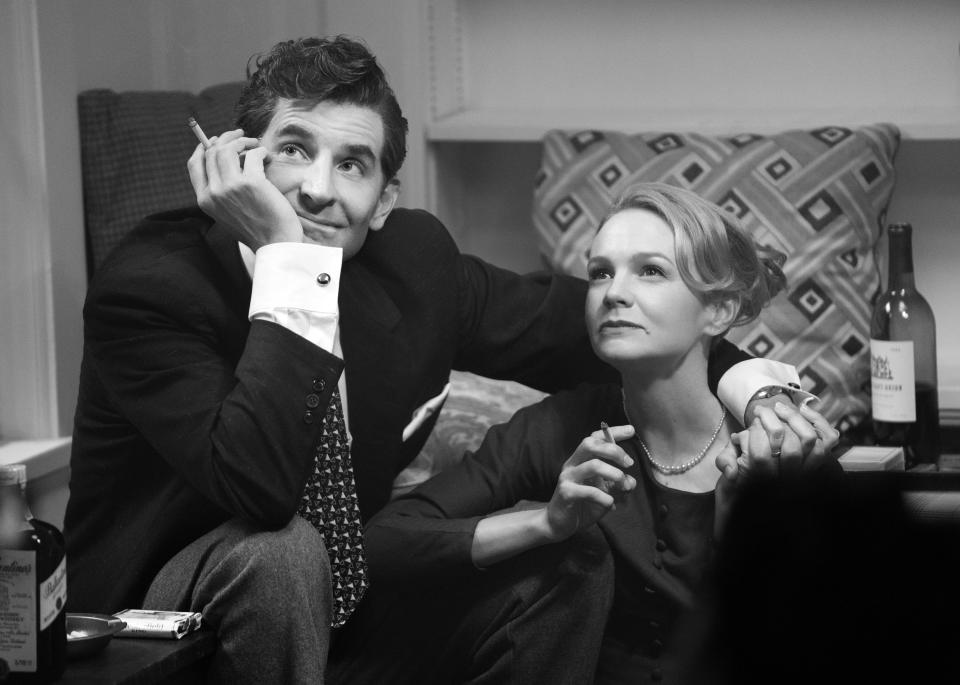

Maestro

Script by Bradley Cooper and Josh Singer

Essay by Guillermo del Toro

Bradley Cooper is a man of uncommon intelligence. He does not seek what has been found before. He wants to venture into undiscovered territories. When tackling a portrait of a master like Leonard Bernstein, he has to find an angle that has not been seen. To illuminate the man, he organizes a series of emotional moments that seek to reproduce a living moment, rather than a memorial monument. What had that life felt like? What was it like to co-exist as a genius and a man of complex emotions? Bradley Cooper and Josh Singer’s rendering of the legendary conductor and composer/cultural icon in “Maestro” achieves this. It is immersive and emotional and experiential and, above all, cinematic and alive. Their secret was finding the backbone of the story in Felicia Montealegre and Bernstein’s marriage of 27 years. Avoiding the pitfalls of a moral lesson and with tremendous grace, Bradley and Josh fold us into that relationship, crafting it with melodic, conversational dialogue and sharp portraiture across the decades, inviting us into their, at times tumultuous, but always deeply loving relationship. They pay off those building blocks in the end with profound, immediate emotion as we, with Lenny, approach the end of it all. In the whirlwind of a lifetime, love and art may save us all.

Guillermo del Toro’s screenplay credits include “Nightmare Alley,” “The Shape of Water” and “Pan’s Labyrinth”

Nyad

Script by Julia Cox and Diana Nyad

Essay by Terence Winter

I can’t imagine a more solitary activity than long-distance swimming, so the fact that Julia Cox turned Diana Nyad’s story into a powerful, moving screenplay about two friends is what makes it even more extraordinary. Nyad captured the world’s fascination by swimming 110 miles nonstop from Cuba to the Florida Keys, succeeding on her fifth attempt, in 2013. If this sounds superhuman, consider that she did it at 64 years of age.

Played with unapologetic selfishness, Annette Bening as Nyad is so prickly that you half expect Jodie Foster, who plays her coach and best friend Bonnie Stoll, to sock her in the nose. Instead, Stoll weathered her pal’s emotional storms and functioned as one of the unsung heroes in the swimmer’s life who allowed her unyielding determination to fully pay itself off. Nyad knows exactly who she is, what she wants and what she must do to get it. That clarity is a blessing that Foster’s coach Stoll and Nyad’s ship navigator John Bartlett, played by Rhys Ifans, don’t have. Their own dreams are more amorphous, which makes their communications with Nyad even more challenging.

So while the swimming sequences are beautiful and inspirational, Julia Cox’s screenplay is at its poignant best when the characters are on terra firma, struggling to understand, support and love one another.

One of the rules of Nyad’s achievement was that no one was allowed to touch her during the entire journey, not until she walked out of the ocean of her own volition. Watching this solitary warrior fall exhausted into the arms of her best friend, the person she didn’t know she needed more than anything else, then get smothered in love by her teammates, is one of the most moving of moving images I’ve seen in quite a long time.

Terrence Winter’s screenplays include series “The Sopranos,” “Tulsa King,” “Boardwalk Empire” and films such as “The Wolf of Wall Street” and “Bob Marley: One Love.”

Past Lives

Script by Celine Song

Essay by Hua Hsu

I did not know what “Past Lives” was when I came across an arresting image from it: a woman (Greta Lee) and a man (Teo Yoo), sitting in front of a carousel, their gazes communicating worlds of possibility. I was mesmerized. Who are they? What has brought them together? Are they happy or sad, full of desire or curiosity? Maybe he is looking past her, or maybe he can’t turn his head because he is afraid of what he will see.

Who knows how the random people we come across will remap our imaginations, or flitter across our dreams? “Past Lives” is the story of two people, and then three, who live within encounters that might as well have been fleeting, only they were not. Lee, who plays Nora, a Korean American playwright, and Yoo, who plays Hae Sung, a Korean man dissatisfied with his “ordinary” life, are staggeringly good as childhood friends from Korea who, after years out of touch, re-befriend one another online, culminating in a reunion in present-day New York.

Hae Sung’s visit unsettles Nora and her husband Arthur, a Jewish American writer played with a sweet fragility by John Magaro. Though it’s about writers and immigrants and friendship, it is not a story about creative impasses, or the predictable frictions of dislocation or the labors of love. You sense that, in the drawn-out lives of these characters, made real by Song’s luminous script, it could have been about any of these things, maybe some other time, in some other telling of their stories.

Wondering what could have been: it is the immigrant’s favorite pastime. And Song treats these forking paths with a poetic sensitivity. “Past Lives” extends beyond the screen, reminding us of our own pasts, all those potential lives left unexplored. It’s a feat to write so clearly while also guarding the mystery of all that was left unsaid. And there are entire novels inside the way the people in “Past Lives” regard each other, search each other’s faces for clues. We’ll never be on equal footing with one another, whether it’s the friend who doesn’t remember you the right way, or the unknowable, lost memories that comprise the closest people in our lives. But we’re here now.

Hua Hsu is a staff writer on the New Yorker, and author of “Stay True” and “A Floating Chinaman.”

Poor Things

Script by Tony McNamara and Alasdair Gray

Essay by Alan Ball

When my agent told me that Tony McNamara had asked if I would introduce a screening of a film he wrote, “Poor Things,” I was flattered. I was a fan of Tony’s. I had loved “The Favourite,” and I was just getting into his magnificent TV series “The Great.” And so I happily agreed to introduce the film.

I knew Tony was adept at surprising an audience, at writing clever dialogue that great actors can sink their teeth into, at always keeping the emotional foundation of his characters’ behavior alive and understandable. But nothing I knew about his previous work could have prepared me for “Poor Things,” one of the most audaciously original films I have seen in a long time. I was mesmerized, shocked (in the best way), highly amused and thoroughly entertained, and ultimately moved by this inventive tale about the universal human struggle to find one’s authentic self.

One thing about Tony’s work — on which I am now binging — I especially admire is his ability to skate on that razor-sharp line between farce and tragedy. I am reminded of an episode of “The Great” that was delightfully manic and absurd as it progressed and then landed on Catherine’s grief over her dead lover, and her own part in his demise. Her despair felt real; it was literally painful to watch, deeply human and earned and true.

Tony’s writing is distinct and fresh, and one feels the great love he has for his characters and their plights, no matter how insanely or destructive they may act. It’s an act of generosity, one for which I am grateful. And inspired.

Alan Ball has written such series and movies as “True Blood,” “Six Feet Under” and “American Beauty.”

Rustin

Script by Julian Breece and Dustin Lance Black

Essay by Rep. Malcolm Kenyatta

Growing up in the haze of the post-civil rights, yet pre-Black Lives Matter era, one thing was clear. I could be “young, gifted, and Black,” but never “young, gifted, Black AND gay.” After experiencing “Rustin” — because one does not simply watch this film, you are immersed in it — the young child in me rages that this vision wasn’t there as I struggled to come out and engage politically.

Julian Breece’s and Dustin Lance Black’s writing is so illuminative because it’s so authentic, with depth that can only be captured by speaking to those who knew the real Bayard Rustin and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., as they did for this screenplay. It’s not the sanitized versions of these American deities that we’ve come to accept as gospel. It is the small and raw moments that made them men and friends. Whether it’s Rustin, Dr. King or the other civil rights leaders in the film, Breece and Black have a way of revering them yet revealing them in ways that viewers may love or find off-putting, but none can question its humanity.

When you think of the civil rights movement and its momentous legislative accomplishments, few would give credit to a gay Black man from Pennsylvania. In fact, as we see throughout the film, society’s goal was to make sure we did not. Yet “Rustin” forces us to confront that fact that we must. Now, we do.

The tactics of nonviolent resistance first used by Gandhi that made King an icon were taught to him by a gay man. The March on Washington, rightfully hailed as the crowning organizing jewel of the century, again bear the fingerprints of a gay man. Like the leaders in the film, most notably Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., who was positioned as an ongoing antagonist to Rustin, we are asked to remember the civil rights movement in a way that erases the queer realities woven throughout it.

Bayard Rustin was real and this film makes him even more so. In an interview, Breece spoke about the “double consciousness” that is imbued in Black gay men in America. I think it’s the secret sauce to his writings. It’s why this work so seamlessly guides us through the prism and the fullness of Rustin: his flair for the dramatic, his superhuman organizing ability, his human desire for love and lust. It’s all on display.

It is hard, especially for young people, to be what we can’t see. When I was a young Black kid from North Philadelphia, I needed to see this. I didn’t have it as a kid, but I am so grateful a new generation will.

State Rep. Malcolm Kenyatta (D-Pennsylvania) chairs the Presidential Advisory Commission on Black Americans.

Saltburn

Script by Emerald Fennell

Essay by Charli XCX

I grew up in Hertfordshire, a home counties area just out of reach of London. Chaos and excitement felt close, but not close enough and so in my early teen years I raised myself on a diet of MySpace, “Skins” and stick figure musicians with lopsided hair that I’d often read about in the NME. School friends were either embracing Effy Stoneham as their idol and trying their hand at badly rolled cigarettes, or positioning themselves as the polar opposite: Jack Wills wearing Hugo, or Sara types who often embellished every other sentence with a long drawn out “maaaaate.” Watching “Saltburn,” therefore, left me triggered as I saw both of these realities collide in Emerald Fennell’s semi-gothic, semi-Tumblr coded depiction of 2007.

Emerald Fennell IS the devil in the details. I’m not sure whether it was the reminder of Livestrong bands being the accessory of the moment, the reality that a lot of posh people are actually called Henry or the epic fail of the boy at the party frustratingly saying he’d been “chirpsing” his conquest all night to no avail, but Emerald’s flair for delicious specifics really transports the audience back to THAT time.

A self-confessed Paris Hilton and Britney Spears stan, Fennell obviously appreciates the value of the poptastic — and thank God because I, for one, NEED that to continue to thrive on the big screen in a post-“Barbie” climate. She understands the moreishness of pop culture sprinkled with high art and explores the depth of emptiness in language with literal LOL results most evident with Rosamund Pike giving us absolutely nothing and EVERYTHING with her delivery of the line “Bliss!” And, honestly, what would 2023 even BE without Barry Keoghan slurping Jacob Elordi’s cum from a drain?! No, but seriously, the homage to the gay gothic genre throughout this twisted romp was absolutely fabulous and whilst I’m hesitant to say that I identify with Keoghan’s character for obvious reasons, Fennell reminded me of the searing pain that is being the outsider looking in. P.S. the music slapped.

Singer-songwriter Charli XCX’s hits include “Boom Clap,” “Fancy,” “I Love It” and “Good Ones.”

Best of Variety