Writer shut the door on mom's death, only to confront pungent, ghostly bite back

When my mother died a bad death on the one-year anniversary of my brother’s bad death, I closed her bedroom window and shut her bedroom door and did not open either again for six months.

When I did, I discovered more than a memory of my mother had lingered.

And she was not pleased.

Mom: A perfume-loving pistol

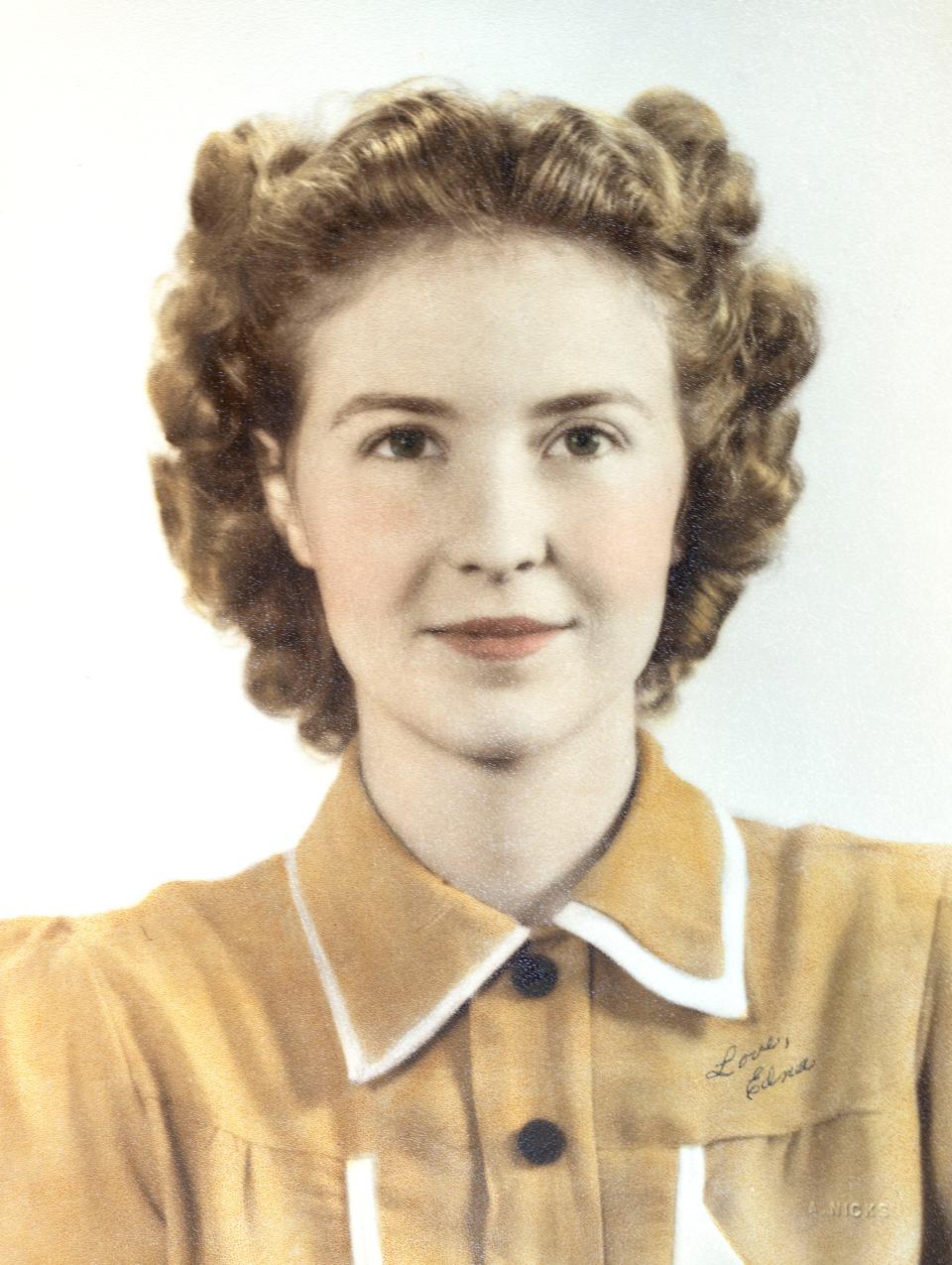

I was born on the Day of the Dead to a wild-hearted woman whose own mother could have run with wolves.

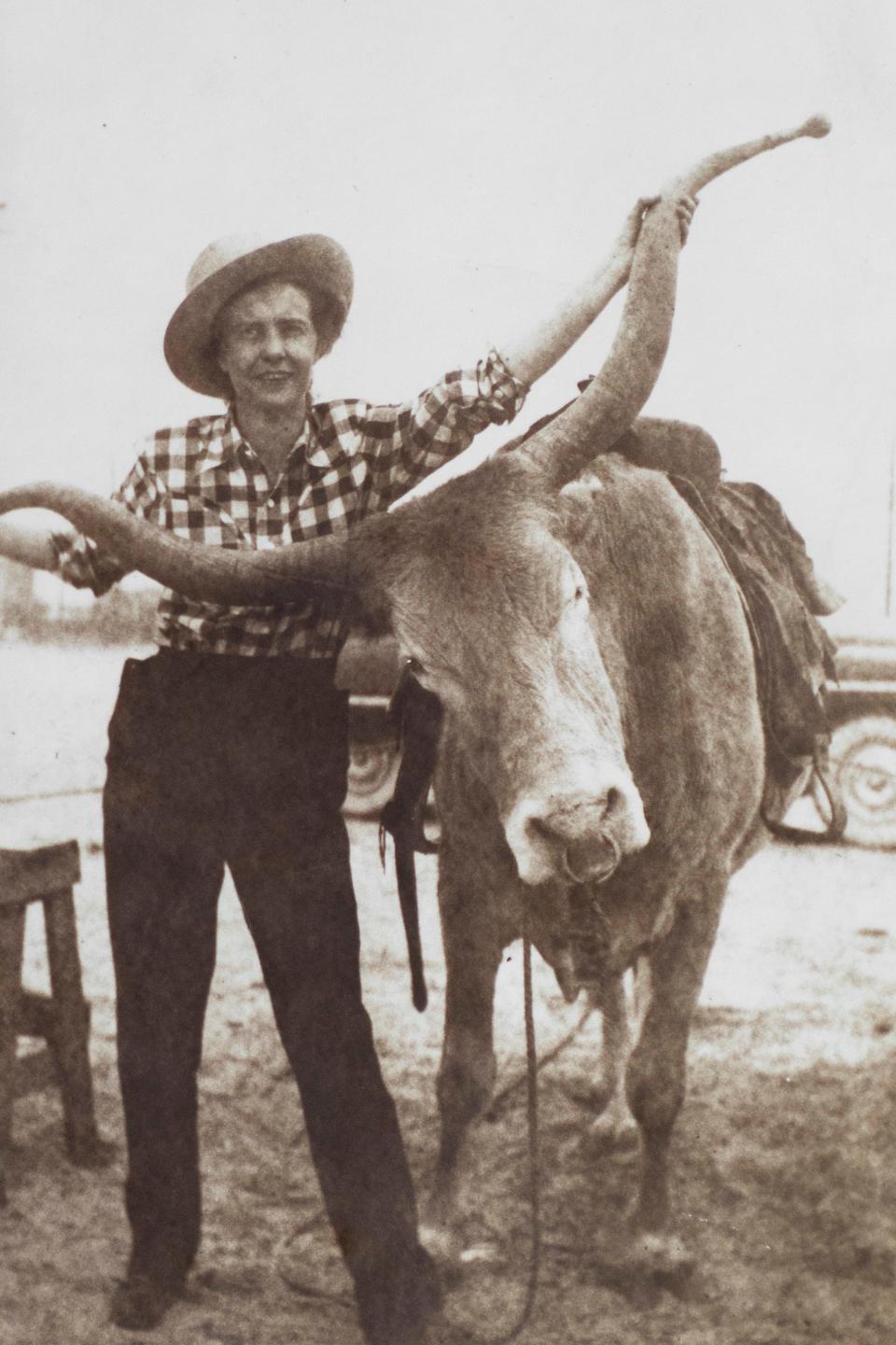

Edna Mae Perkins rode a long-horned steer. She learned to drive — though not how to back up — in a single night so that she could follow my father as WWII sent him to military bases across the country. A Southern Baptist, she thought the ban against dancing was silly and the prohibition on wearing shorts a crime against comfort. She chafed at the restrictions of her era: She could not buy a washing machine in cash without her father’s signature.

Books were her water and murder mysteries were the best. Agatha Christie’s Poirot and Miss Marple, Ngaio Marsh’s Nero Wolfe, Dashiell Hammett’s Thin Man crowded our living room bookshelves and side tables. (I read because my mother read, and thus was wise in the ways of poisoning long before I mastered my fourth-grade multiplication tables.)

More: Halloween: Where to find the best events with fun, fright, gore in Palm Beach County

She loved shoes and butter; the Great Depression having deprived her of both. And while some women will not go out of the house without lipstick or earrings, she would not leave the house without perfume. Not at 19, and not at 98.

Estee Lauder’s Youth Dew is pleasant enough; but for years, the windows in her apartment stayed closed, as air conditioning and heating counterbalanced her aging body’s difficulty in regulating temperature.

True, the front door opened and closed when she left to play bridge and Texas Hold ‘em with her spry young friends of 80 or so or drove to Key West with them on a whim.

But these short front door breezes did not put a dent in the accumulating layers of perfume.

It clung to her clothes even after washing. It seeped into the bath towels and pillowcases.

Her favorite recliner was a perfumer’s paradise. The carpet was a wall-to-wall sachet.

And it traveled, as my youngest son discovered when he opened his suitcase after a weekend visit, and Estee Lauder drifted up from his T-shirts and socks.

“Granny perfume,” he laughed, before he headed for the washer and set his suitcase on the porch for a two-day airing.

For all the intensity, it was never overwhelming. It was never cloying or stale. It was simply there, the fragrant backdrop to her life.

And when it came time for her to leave the apartment and move in with me, the scent settled into the packing crates and navigated the four-hour drive south without so much as a lost molecule.

It wafted out of the moving van and settled in: in her two closets, the little sitting room, the storage unit with her overflow of shoes and purses, and her bedroom. Mostly, the bedroom.

She played cards, mastered her Kindle, carefully followed the news and was burning through the fourth installment of Harry Potter when she slipped and fell.

She survived surgery, humor intact. But Florida’s COVID politics ensured not only that she would never come home, but also that she would die in exactly the way she had most feared: alone.

And I could not get to her before she did; could not sit with her as I had with my brother, could not hold the memorial service she had so meticulously planned without risking a similar lonely death for her elderly friends. Grief layered on grief. I could not let it go.

But I could lock in her perfume.

And so I closed her bedroom door.

Where death blooms

Do we believe what we see? Or can we only see what we believe?

Our brains are hardwired to create patterns from chaos. We are born storytellers, constantly spinning internal narratives to explain the world: why our friend is late for coffee or our husband is moody; why the grocery store clerk snapped at us; the motivation behind a politician’s lie; the persistent math of the chambered nautilus; the space between stars.

What happens when we die.

The story told by my grandfather’s family went like this: Before anyone in his family died, another long-dead family member would first appear.

My grandfather was a frowning man. His scowl could bend steel. But when he told my grandmother that his mother had come to him, his voice shook, she later said. Two weeks later, he died of a heart attack.

Before my friend Paul, the avid gardener, passed, he tried to rekindle my own lost passion for gardening with potted gifts of greenery: cuttings from his own plants and once, to my dismay, a frangipani.

Every plant has its bloom time, and every plant has its duller dormancy, but stripped of its flowers, the frangipani sets world records for ugly. The branches are gnarled. The bark is a scaly gray green. When leaves drop, they leave a pock mark behind. And just for good measure, it has murder in its heart: The sap is poisonous.

I left it to wilt.

Two days after Paul fell ill and abruptly died, my youngest son came into the house.

“Mom, have you been outside?”

My yard had long ago been seeded, shrubbed and treed for flowers, but all emerge in their own season, at different times and at different paces: some slowly, some suddenly, some in spring, some in fall.

Every plant in the yard was in bloom, in riotous defiance of science and season.

Even the long-ignored frangipani.

In India, they say the frangipani is a symbol of immortality. Even lifted from the soil, it may continue to flower.

In Vietnam, I am told, a frangipani’s white flowers are home to ghosts.

Explore 55 fun must-try things to do in Palm Beach County

***

A very unhappy odor

Locked in her empty bedroom, my mother’s perfume soured.

In the decades it had permeated her closed apartment, it had never repelled, never turned rancid.

But when I finally opened the door to the room where she had spent only months, the sweet had a burnt edge to it. And it was suffocating.

I thinned her closet. I wiped down some surfaces and painted over others. I emptied the room of things perfume might cling to: clothing, sheets, papers.

It didn’t work.

Finally, I opened the window.

The perfume didn’t leave. It sweetened.

I closed the window when I left.

The next morning, the perfume reeked again.

This went on for weeks. Persistently sweet when I left the window open.

Sour when I shut it in.

The intensity never changed, only the bitterness of the bouquet.

I began leaving the door ajar. The window open for hours at a time.

Until, finally, I could sit in her room and breathe again and wonder at what message, exactly, I had been locking away?

Sitting with mysteries

It has been two years since I opened her bedroom door. Even now, I can catch the sweetest, subtlest scent of the puzzle that my mother, who so loved mysteries, left for me.

I could tell myself a story about this. I could bludgeon it into the box of a solved riddle, or theological testament, or scientific theorem. One or all might even be true.

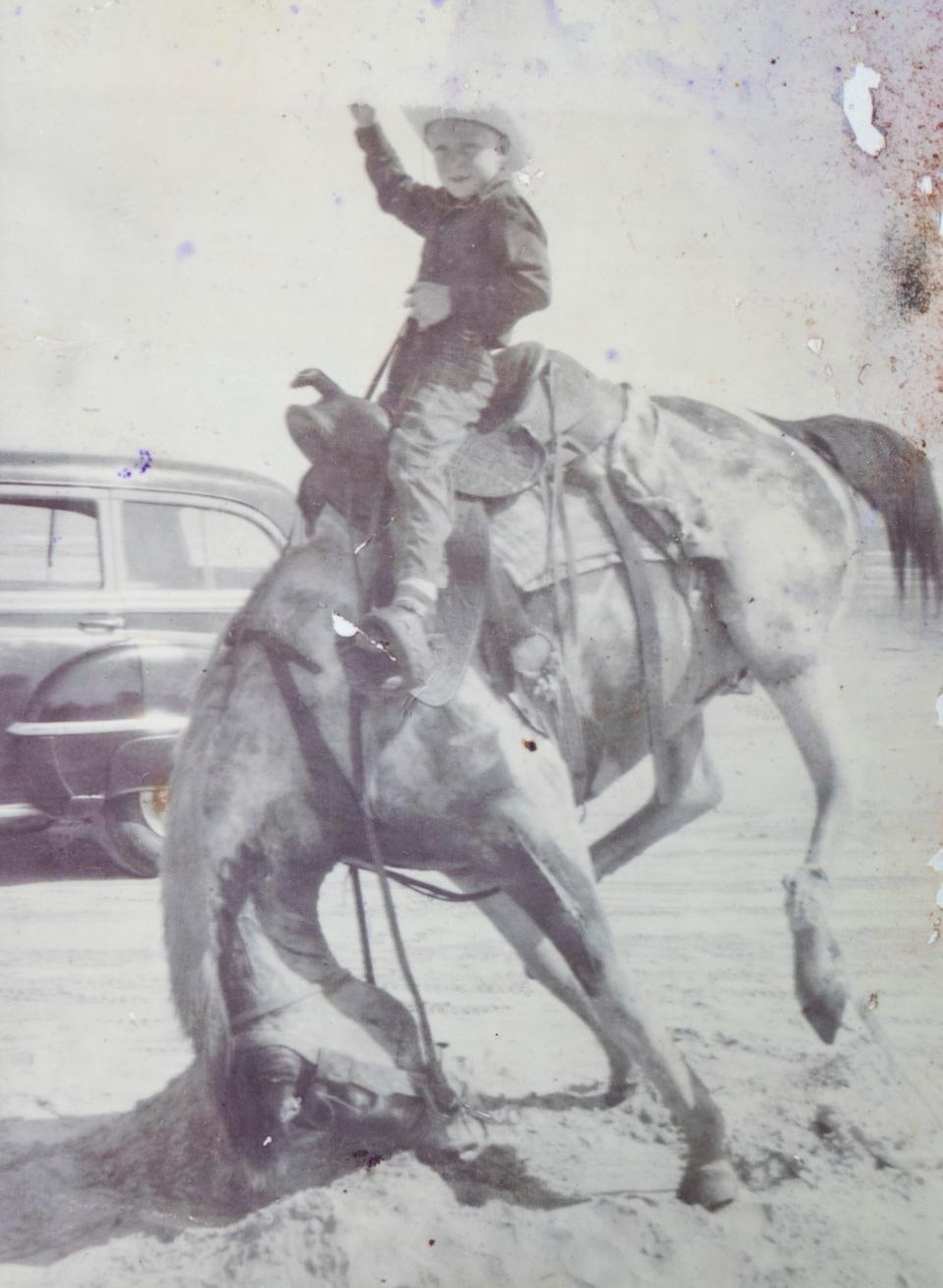

But how I sit in that room with my mother’s Buddhas and my brother’s worn cowboy boots; how memories become restorative companions instead of knife-sharp regrets; how the wind moves the lace curtains of that open window to let in the scent of unexpected blooms — none of it requires an answer, or even a belief. None of it demands anything at all.

A devout Christian, my mother believed that there were doors beyond doors. If so, there is a door for me, too. I don’t dwell on what might be beyond it. We all find out soon enough.

But in my mind’s eye, I could see myself passing across a threshold into a fragrant cloud. I would breathe deeply, I imagine, and follow the trail of flowers my mother laid for me to come and find her.

Pat Beall is a former Palm Beach Post reporter.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Dead mom leaves mystery behind closed doors for daughter to ponder