‘Our World Is More Steely Dan Than It’s Ever Been’: Why the Seventies Jazz-Rock Cynics Sound Perfect Right Now

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

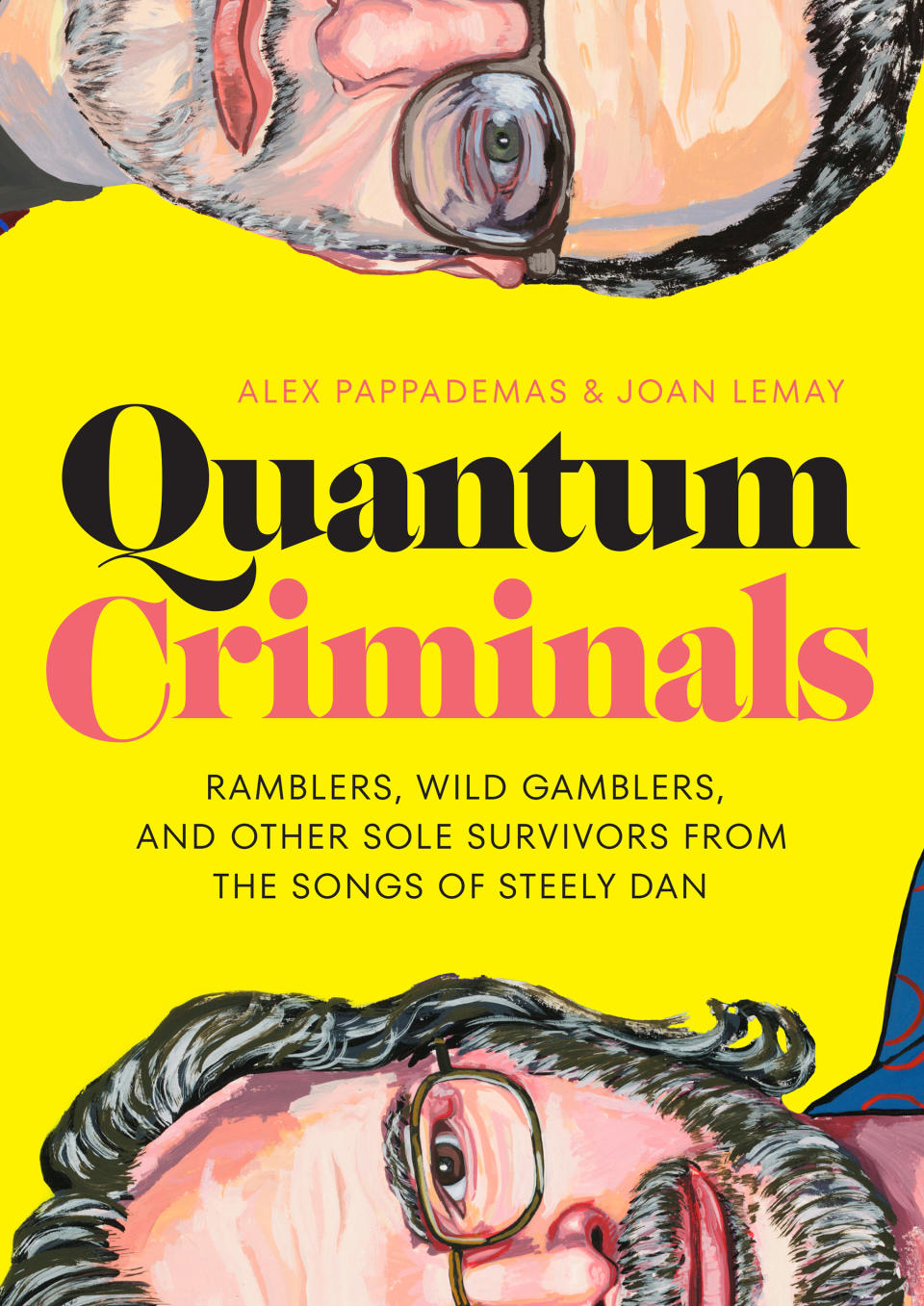

You could fill a book with all the shady characters you meet in Steely Dan songs. Quantum Criminals is that book. Journalist Alex Pappademas and artist Joan LeMay take a deep dive into the genius of Steely Dan, and the strange world that Donald Fagen and Walter Becker built together. LeMay illustrates her favorite Dan characters, from Rikki to Kid Charlemagne, from Dr. Wu to Peg, all the way to the El Supremo in the room at the top of the stairs. Pappademas gives a mind-bending guided tour of the Steely Dan universe, exploring their songs, their legend, their negative charisma, their decadent love affair with L.A. Quantum Criminals is one of the sharpest, funniest, and best books ever about any rock artist.

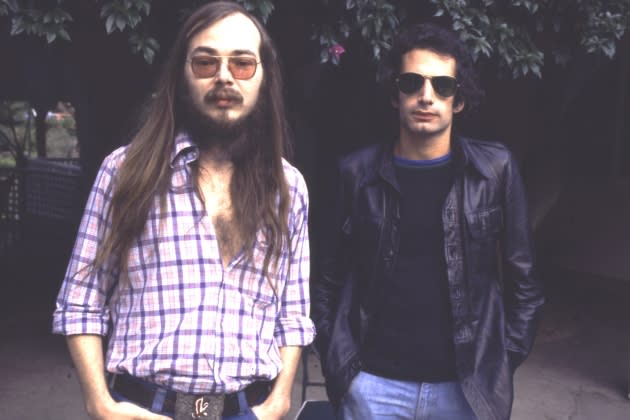

People are more obsessed with these Seventies jazz-rock cynics than ever these days. As Pappademas writes, “Around 2020 an ongoing groundswell of semi-ironic Dan appreciation became a full-fledged revival.” Dan culture keeps growing, with newsletters like Expanding Dan, podcasts, and the brilliant Twitter account @baddantakes. Pappademas theorizes, “Steely Dan are an endlessly meme-able band because they’re a hilarious concept on paper—two grumpy-looking guys obsessed with making the smoothest music of all time.”

More from Rolling Stone

Joni Mitchell's Surprise Newport Folk Concert to Be Released as Live Album

Steely Dan Weren't Hip-Hop, Even if 'Everything About Them Was Hip-Hop'

Watch Joni Mitchell Perform 'Summertime' at Gershwin Prize Concert

But maybe this revival also means they were ahead of their time. Pappademas writes, “If more people are ready for Steely Dan in the Twenties than they were in the Nineties—or even the Seventies—it’s because our fast-warming world is more Steely Dannish than it’s ever been.”

Pappademas spoke to Rolling Stone about the weirdly timeless appeal of Steely Dan, the current Danaissance, the “yacht-rock” question, the “Deacon Blues”/Star Trek connection, his favorite drum solo, and how ironic fandom can lead to the real thing.

How did you begin your personal Steely Dan journey?

It all started with an ironic purchase. At the moment I was coming of age, Steely Dan’s stock was pretty low. I was a young man who consumed a lot of older rock-critic opinions, and I assumed this band was not for me, which is funny because it’s clearly SO for me. I would ignorantly make fun of Steely Dan and then go listen to Pavement, which is in the same vein—musical sophistication meets irony. But I bought Katy Lied because the Minutemen had covered “Dr. Wu” and I wanted to know what the original sounded like. I remember everything I bought that day: a Tortoise remix 12-inch, Miles Davis, Isley Brothers. But I thought, “Yeah, let’s take a flyer for a buck on a Steely Dan album.”

And that’s how the seed gets planted. Because you can try to ironically enjoy Steely Dan, but they’re already ahead of you on that. They were the first yacht-rock parody before yacht-rock existed. A song like “Any Major Dude” has more in common with the Blue Jean Committee or the fake Steely Dan song in Oh, Hello. It’s like they’re already making the parody version before the genuine article existed. And a lot of yacht-rock I think is just Steely Dan with like one less chord and a lot less irony.

Your origin story is just like mine. For me, it was ironically buying Pretzel Logic within days of turning 30. Totally stereotypical.

Yeah, that biological clock starts ticking and you gotta get a Steely Dan album. They are always waiting for you on the other side of 30. But with the Dan revival that’s happening now, it’s a product of the internet, where those prejudices don’t exist. They’re not something that people have to overcome in order to get into Steely Dan. So the 19-year-olds are into it. There was a post on the Steely Dan Reddit asking people for their age, and it was remarkable because they were all in their 20s. It’s not boomers making those Steely Dan memes we’re all passing around. Something has happened. It’s airborne and contagious, in a way it never was back in the day.

Why is this Steely Danaissance happening now? Why do they speak to our moment?

We’re more cynical. We’re all looking out at the world with a Donald and Walter-ish kind of dismay. So they make a lot more sense now. What seemed cold and remote and jerky about them back in the day—now, that’s just the way people talk. They’re also also writing apocalyptically about their time, and our time now seems so unavoidably apocalyptic. It really does feel like California is sliding into the sea along with the rest of America. So the time is is finally right for them. It only took 50 years.

The Steely Dan/Gen Z connection seems like a parallel to Joni Mitchell. Gen Z just gets them on a deeper level than any previous generation did.

Joni is definitely a parallel. She has a similar arc—she gets smoother and jazzier as she goes on. But it’s like what Robert Christgau wrote about Blue: as her sound gets more and more California, her satire of California gets sharper. As she embraces the musical ethos of her moment, she becomes a better satirist of the sexual and spiritual ethos. And that’s Gaucho. They mastered the smooth sound of the Seventies, yet it’s their best parody of California. It’s their most savage satire of their world, just as they were embraced by that world.

At the end, Steely Dan are peers of the Eagles, as opposed to people on the outside making fun of the Eagles. Donald is there at the Eagles vs. Rolling Stone softball game. [Note: This grudge match really happened, and the band kicked our asses, 15-8.] But he’s sitting in the Eagles rooting section, not the rock-critics rooting section.

The book keeps coming back to the eternal question of what Walter Becker did. You sum it up as “plausible deniability.” That’s a perfect explanation.

It’s the two of them, so they can say, “If you don’t like this, it came from the other guy.” But they become this other person, and that other person can get away with saying things and suggesting things that Donald or Walter wouldn’t say. I borrowed the idea from [science fiction legend] William Gibson about “Mr. Steely Dan” as a sort of collective protagonist identity that’s part Donald, part Walter. But it’s also a third person that exists from the fusion of the two, who’s maybe them, maybe not—you’re not sure. But he doesn’t necessarily have to be a laudable character. Walter was so essential to the voice of Mr. Steely Dan. As Donald said, “He finishes the things I can’t finish.” He was more of a Steely Dan character than Donald was, as the years went by—he was living the life as well as documenting the life.

You assume that the narrator of “Fire and Rain” is James Taylor, and you assume that the narrator of “Heart of Gold” is Neil Young, because there’s a guy with a guitar telling you something. But Steely Dan have all of these distancing devices in place. You understand you’re not being told the story straight—it’s coming at you sideways. Stephen Malkmus has that great quote about them: “If you avoid the first person, your music becomes frightening, as if composed by phantoms.” That phantom quality, that question of who wrote what, inflects everything Steely Dan did.

How did you two devise the format for this book—Joan LeMay illustrates the song characters, you write about them?

This was two projects that merged into one. Jessica Hopper started working as an editor on the American Music Series and asked me, “Is there somebody you could write a music book about?” So I thought, “Who am I never tired of thinking about? Steely Dan.” Meanwhile, Joan was gonna do a zine where where she drew every character in every Steely Dan song. Jessica said, “Joan, this is not a zine. This is a book.” So these two things came together. But we didn’t try to define these characters. Anything I wrote that felt like fan-fiction got cut immediately. You don’t wanna be filling in the holes in these stories too much.

You write about how Steely Dan create these unsavory, untrustworthy, unlikeable, quasi-inhuman L.A. characters. They seem close to Randy Newman that way. Is there a connection?

Randy’s one of the closest comps. He’s clearly not writing about Randy Newman’s own beliefs. He’s one of the few solo artists working that same “plausible deniability” thing as Steely Dan. But there’s a big difference—maybe it’s the influence of the movies. He’s very much a creature of L.A., he’s from generations of Hollywood, whereas they arrived from New York with a very New York sensibility, confronting the realities of Los Angeles. Randy is able to function in that world—he’s comfortable hanging out in Beverly Hills and enjoying it, while Steely Dan are more like exiles in Malibu beach houses. Steely Dan are looking around them and satirizing their milieu, whereas Randy is looking out at America and writing songs like “Rednecks.” He has America as a concept the way Steely Dan have L.A. as a concept. Randy LOVED L.A., you know?

Steely Dan loved L.A. too. Donald had a great line in 1977: “We’re not as negative as the Eagles. They’re totally down on California.” Steely Dan came to L.A. and found it hilarious. If you get into the Eagles, who are the the nemesis in this book in some ways—but when the Eagles started writing negatively about California, it wasn’t funny to them. They were very upset about the depravity they were seeing at the Hotel California. Whereas if Steely Dan wrote “Hotel California,” it would be about somebody saying, “Isn’t this hotel great? We got pink champagne! You can go do a Satan murder in the back if you want to!” Both bands are singing about self-delusion, but Steely Dan are singing in the voice of self-delusion, instead of describing self-delusion.

Something about the current Danaissance: it seems the newer fans are mostly into the later albums. It’s almost like they’re now the band that made Aja and Gaucho, with everything else as just a prologue.

Those first four albums are less talked about. It’s songs of innocence vs. songs of experience, right? There’s a lot of angry young Dan on those first records. When you get to the later albums, with the really slick surfaces, that’s what we think of as Steely Dan. But my favorite one is Countdown to Ecstasy, and its stock seems so low right now. It’s still their worst-selling album ever. It’s the coolest Steely Dan record, because it’s the only band record. When you listen to those live bootlegs from ’74, they’re a shit-hot band, but they turned their backs on that. So that album is still not talked about enough. There’s amazing stuff on Pretzel Logic—best album cover, too. The Royal Scam, worst cover.

Gaucho has gone from most-hated to arguably most-loved.

Gaucho is the ultimate one because it’s the slickest. This is what happens if you take slickness too far—this is the ruin that you will come to. They build this incredibly complicated drum machine to excise the human element and the human feel. Gaucho is where it ends—you can’t go further. The human mind can only take so much slickness. But that’s essential to what we love about Steely Dan—flawed humans trying to create perfection. They go mad trying to fix everything and make it perfect, trying to solve the problem of humanity in music. And eventually the solution is, “We’re going to invent sampling so that we can reduce the amount of human error.”

You quote the guitarist Denny Dias on recording Katy Lied, and he says it all went wrong in the studio because of “human error.” He sounds like HAL 9000 in 2001. “This music is too important to be jeopardized by human error. We clearly need to kill the astronauts.”

Steely Dan managed to kill all the astronauts. That’s what Gaucho is—that’s when HAL is fully driving the ship through the black hole. Even Walter is out of the picture at that point. So Donald, I guess that makes him Dave Bowman, trying to land on the water.

The reason they stopped touring is because they couldn’t do it exactly like the records. And that they found that very frustrating. They heard all these mistakes and flubs. That’s what so great about Countdown—it feels loose, like “Let’s let Skunk Baxter drive for a minute.” I wish there was more of that, but it’s not Steely Dan if they allow that to happen. And so they start gradually making it much more careful and more intense and then it becomes something different. It becomes like this kind of weird cocaine chamber music by the end.

There’s so much mystique about their sidemen.

Everybody wanted to play on a Steely Dan record because they got to really use what they were good at. They were these in-demand session dudes, so for them it’s okay, dog-food commercial at 11, then Steely Dan at 2:30, then Three Dog Night at 3:45. It was this magical place for the session dudes where they could really get into it, because as much as Donald and Walter were these exacting studio sticklers, they were looking for everybody’s best idea. They wanted the Brecker brothers, the L.A. cats, the New York cats. And even those guys were found wanting. Donald and Walter would hire these high-price session dudes, fire them all at the end of the day, then bring in different high-price guys every day. It’s almost like they did it on purpose, to live up to their legend.

It wasn’t about getting the biggest name. It was about whoever had the best idea. A role player could be God in that moment if he really brought it. The counter-example would be bringing in Mark Knopfler to play on “Time Out of Mind,” for 9 hours of sessions. And the featured part of Knopfler in that track is literally the first 15 seconds. Then it’s like “thanks, Mark—that’s all.” And it’s the great Mark Knopfler. It isn’t about stars, it’s about getting the best part.

One of the best chapters is where you analyze the Classic Albums: Aja documentary. There’s the famous scene where they’re at the studio console, listening to all the rejected guitar solos for “Peg,” doing their bitchy commentary. What does that moment mean to you?

Ultimately, Steely Dan is the relationship between Donald and Walter, and we get to peek into it through this. It’s not first and foremost a relationship with the audience. It’s about these two guys amusing each other, like they’re podcasters or something, making each other laugh. We get to eavesdrop on that, but at the end of the day, it’s about the two of them. The mind-meld that’s happening. At that time, this documentary was the only artifact we had—the only way we had of seeing them. That moment at the console—I could watch all the outtakes of that moment.

Time to draft your all-star team. Your favorite drum break on a Steely Dan record?

I have to go with “Aja,” the amazing Steve Gadd. If I could play drums, just sit down like Garth from Wayne’s World and do any drum break, it would be that “Aja” break, including the little stick clicks in the middle of it. That song is peak after peak, with Wayne Shorter just blowing it out. But my favorite Steely Dan drummer has to be Bernard Purdie, playing the “Purdie shuffle” on things like The Royal Scam, when they came back to New York.

Best sax solo?

I don’t wanna say Wayne again, but it’s hard not to. Wayne’s the greatest. That’s the truest jazz moment—it’s like a cosmic wind is blowing through that song at that moment. But I might give it to Pete Christlieb on “Deacon Blues,” the sax player that they recruited from the Tonight Show band to play on this song. They were watching the Tonight Show, heard him, and said, THAT guy. He’s a working musician who happens to work on the song about learning to work the saxophone. In that moment, he IS Deacon Blues. He’s had an amazing long career—he ends up in the Star Trek orchestra, on The Next Generation.

So he’s the intersection between the Star Trek Universe and the Steely Dan Universe? What a terrifying idea.

Yeah, it’s like a picture of Walter with a Klingon forehead or something. Guitar solos are easier for me. I really like the one in “The Royal Scam.” That’s where you’re working your way up to Larry Carlton’s work on Hill Street Blues, that TV cop jazz of the Eighties.

Best vocal?

“Your Gold Teeth II” is an incredible Donald vocal. He’s fascinating as a singer because he didn’t think of himself that way. They never really intended to become a band, but he certainly didn’t intend to be the lead singer of a band. He fought against it for a long time. That’s why they had David Palmer on the first record—they needed a frontman who looked like a frontman. Palmer’s perfect for that—he looks like he’s from the same lab as Peter Frampton. Donald can’t hit those high notes, but the sound of Donald working within his limitations is the sound of Steely Dan to me. In that song, there’s something so emotionally huge in what he’s doing. It’s the more reflective of the “Your Gold Teeth” songs.

The other “Your Gold Teeth” [on Countdown] is just weird. That’s where they reference “Cathy Berberian,” like it’s a name everybody would know. “Even Cathy Berberian knows there’s one roulade she can’t sing.” She was an avant-garde singer/composer, worked with John Cage and Stravinksy. But they just throw that in there, at a time when nobody could Google it. People must’ve thought, “That’s some friend of theirs.” And it has nothing to do with the rest of the song—just the most random, far-out name they could reference. It’s great that they don’t feel the need to footnote it—it’s just them saying, “Wouldn’t it be crazy if we put Cathy Berberian’s name in this song?”

Just planting a seed to grow later.

Exactly. “Somebody writing a book of essays about Steely Dan is gonna love this in about 30, 40 years.”

In a way that’s the theme of the whole book—we get so obsessive over micro-Dan details like this. Isn’t it weird people are so ready for a deep dive like this now?

Joan and I wanted this to be like the Steely Dan Handbook that would be for sale in the head shop, back in the day. I wanted it to feel like this insane eruption of fandom. When we started doing this, it was a weird obscure idea for a book, and now it’s like a total normie idea for a book. We felt like it was niche, but it ceased to be niche while we working on it, which is great. We welcome everybody to the party. We have the fine Colombian and the Cuervo Gold for you. Join us.

I remember when you were the only person I knew who liked The Royal Scam. That seemed like such a contrarian take.

I feel like that was because we were all obsessed, the Spin [magazine] bros. That is what we would listen to. When I was there, working at a rock magazine, it was the peak of the New New York, and all the Meet Me in the Bathroom era was happening all around us. And our job was to be very much enthusiastic about what was going on in that moment. Keeping our jobs depended on that a little bit. “Oh, you wanna keep your health insurance? You get fucking excited about the Mooney Suzuki, man.” And a lot of that music is incredible, but at the end of a long day of being stoked about whatever was happening down at 7B or wherever, you don’t necessarily wanna come home from McDonald’s and eat hamburgers. It was a contrarian position and it was a weird kind of rebellion that we were engaged in: “We’re gonna go home and listen to Dick’s Picks and Steely Dan.”

We were rock critics who just wanted a dive bar with a giant jukebox that had every Steely Dan record on it. That’s how this happens—that’s how you start to think too much about Steely Dan. You sit around with friends saying, “What does this even mean?”

Best of Rolling Stone