‘Woman of the Hour’ Review: Anna Kendrick’s Directorial Debut Is Chilling Even When It Stumbles

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Last year, Anna Kendrick starred in Mary Nighy’s disquieting drama of abuse Alice, Darling. The actress played a woman undone by her partner’s psychological manipulations, pulling from her own experiences in an abusive relationship to shape the character. Her performance — sensitive, gripping — sustained the film’s atmosphere of dread.

In Woman of the Hour, Kendrick builds on the work she started in Alice, Darling — but now she is also behind the camera for this unnerving dramatization of serial killer Rodney Alcala’s appearance on a dating game show while in the midst of his murder spree. Woman of the Hour, which premiered at TIFF before its Netflix acquisition, is an ambitious attempt to subvert true-crime genre expectations by giving voice to the survivors and victims of Alcala’s rampage.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

The film experiments with time jumps and perspective shifts to create an impressionistic portrait of the murders. Its action kicks off in 1977 with Rodney, a photographer (Daniel Zovatto), coaxing a woman named Sarah (Kelley Jakle, Pitch Perfect) into relaxing and sharing details of her personal life. The pair are conducting a photo shoot in a remote mountain region of Wyoming. Their flirty banter takes on a sinister edge when Rodney caresses the woman’s face and tries to choke her. A chase, a struggle and her death follow. Most of the murders depicted in Woman of the Hour adhere to this pattern, underscoring the brutality of Rodney’s process.

A time jump brings us to 1978, where we meet Cheryl (Kendrick), an aspiring actress living in Los Angeles. She is in the middle of an audition where casting directors critique her performance in callous, objectifying terms. Kendrick, as director, is particularly interested in close-ups of the body and portraying physical imposition. She and DP Zach Kuperstein focus on the way Rodney grips Sarah’s torso and how the young woman kicks her legs in an attempt to break free. When Cheryl returns to her apartment after the failed audition, the camera trains us to observe how her neighbor (Pete Holmes), a man with a clear crush, blocks her path to force conversation. These moments initiate a visual grammar that the film abandons as it builds to its climactic scene.

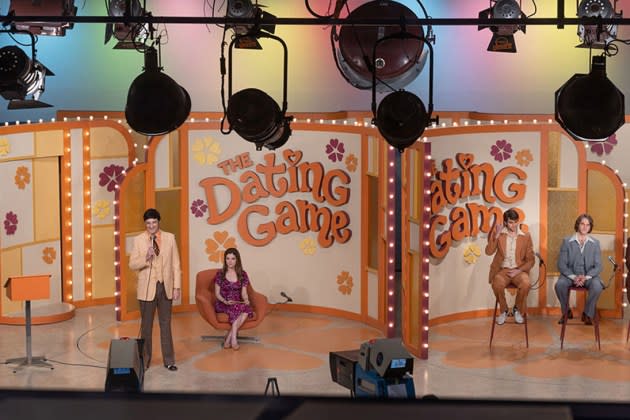

The Dating Game, like its contemporary counterparts, is a platform for misogyny and sexism. When Cheryl’s agent books her as a contestant, the actress hesitates to accept the job. A few reminders about her stagnant career push her to say yes, and as Rodney continues murdering women, Cheryl prepares for her debut. Woman of the Hour’s time shifts become harder to follow as it works toward Rodney and Cheryl’s paths intersecting.

The film introduces Rodney’s victims only moments before they are murdered, which turns them into narrative ciphers. The non-chronological hopscotching makes it hard to determine what has happened before Rodney’s appearance on the game show and what transpires after. Zovatto, who played the sinister prophet character in Station Eleven, channels a similar energy as the serial killer in Woman of the Hour. His performance — marked by an unhurried walk to attack his target and a chilling half-smile — is the foundation onto which Kendrick and screenwriter Ian MacAllister McDonald build the film’s anxious and jittery atmosphere.

Woman of the Hour feels most fully realized when Cheryl and Rodney meet on The Dating Game, on which he appears as a contestant. By this point we know he is a killer and, thanks to Kendrick’s performance, we have built some sympathy for Cheryl (an otherwise shallow character). This ups the stakes of their interactions, mediated by the presence of a live audience and the show’s host (Tony Hale). Among the people watching The Dating Game that day is Laura (Nicolette Robinson), a woman who immediately recognizes Rodney and tries to warn the show’s producers. Portraying this situation as a thriller-esque race against time — assisted by Ramy composers Dan Romer and Mike Tuccillo’s score — heightens Woman of the Hour’s unsettling mood.

The film pulls off the tension of the pivotal moment when Cheryl, perturbed by Rodney’s attitude, tries to escape his attention, but it stumbles on its way to its high-wire finale. In another timeline, this one in 1979, we meet Amy (an excellent Autumn Best), a homeless teenager who encounters Rodney in California. Her story also ends with escape, and her harrowing journey to safety affirms that despite Woman of the Hour’s sometimes shaky execution, its story is undeniably powerful.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Kim Cattrall and Five Actors Who Made Surprising Returns to a Role

10 Times Hollywood Predicted the Scary (or Not So Scary) Future of AI

21 Actors Who Committed to Method Acting at Some Point in Their Career