William Friedkin's 'Blue Chips' Is Better Than You Remember

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The 1990s weren’t kind to William Friedkin. The director, who died this week at 87, had drifted a long way from his days as a filmmaker who helped reshape Hollywood in the late-1960s and ‘70s. His movies weren’t drawing at the box office the way The French Connection and The Exorcist had, and the acclaim was even less. He opened the decade with a flop, the horror film The Guardian. He needed a win.

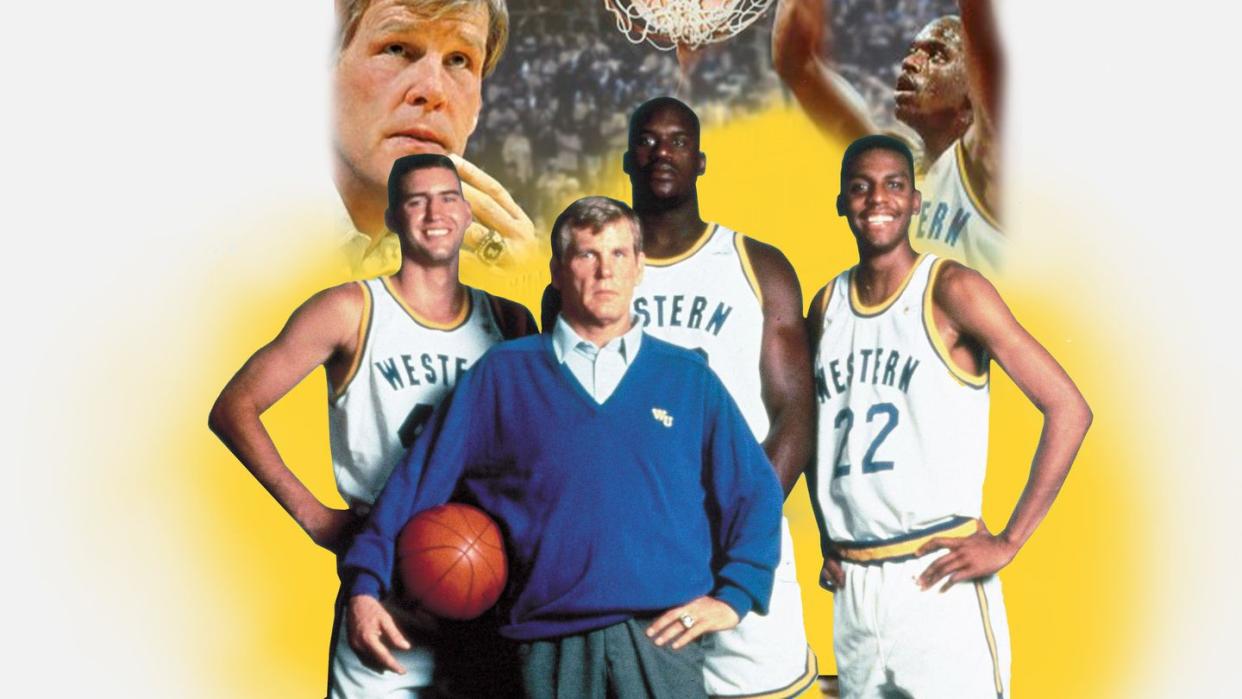

Then came 1994's Blue Chips, a basketball movie with seemingly all the right moves. It starred Shaquille O’Neal, the hottest young player in the NBA, and Nick Nolte, two years removed from People magazine’s “Sexiest Man Alive,” with a script by Ron Shelton, whose earlier projects were 1988’s Bull Durham and 1992’s White Men Can’t Jump. Toss in the electric Memphis State guard Anfernee "Penny" Hardaway, who would later play on the Orlando Magic with Shaq, as well as cameos from some of the biggest names in college basketball, and—on paper, at least—the movie seemed like an easy win. A slam dunk. Pick your sports metaphor.

Nolte's Pete Bell, the coach of a fictional Los Angeles college basketball team that's seen better days, is grappling with school boosters, who are pressuring him to pay players to sign with the school, a practice that ended the career of more than a few coaches in real life. He checks out two top young prospects. One is Butch McRae, played by Hardaway, who's mother will let her son sign in return for a house and a job that gets them out of the inner-city; the other is a guy named Ricky Roe, played by Matt Nover, a former pro player in Europe and Australia in real life, who is a white kid from Indiana, not far from the state’s greatest basketball prodigy with a cameo in the film, Larry Bird. Ricky’s dad wants a new tractor for his kid’s signature.

For Shelton, the idea for a movie that looked at corruption in college sports was a preoccupation. The script was in developmental purgatory for more than a decade, and the writer believed, “Nobody was interested in anything except heroic sports movies.” But America’s interest in basketball had exploded in the ‘90s, and with the success of White Men Can’t Jump, featuring Wesley Snipes and Woody Harrelson hustling on courts around Los Angeles, Paramount scooped up Shelton’s script and attached Friedkin to direct.

But Blue Chips bombed. It showed up at number three in box office returns its first week in theaters, failed to recoup the $35 million budget during wide release, then faded into premium cable obscurity. Most critics panned it. In 2013, Friedkin reflected on the movie's lackluster performance, telling Grantland he was screwed from the start—that it was “impossible” to make a good basketball film. “The thing about basketball is that it’s so spontaneous,” he said. “When I see these coaches drawing up plays and telling guys to go here or there, watch how the players are pretty much not even listening. You can’t control the game.”

I contributed to the film’s $26 million box office haul, and I loved Blue Chips—when I was 13 and saw it at a dollar theater next to a bowling alley. After that, I didn’t think much of it. But it was an auspicious introduction to the work of Friedkin. Eventually, I would dig deeper into his other films, including 1980’s Cruising and 1985’s To Live and Die in L.A. But I had moved on from Blue Chips. Then, in 2020, while scraping the dregs of available content on TV, it popped up on a streaming service and I rewatched the movie for the first time since Clinton was president. I figured I’d fall asleep even before Shaq showed up dunking all over a bunch of nobodies. Instead, I watched from start to finish. By the time the credits rolled, I realized I’d been critic-pilled. Audiences and film reviewers in 1994 were wrong. Blue Chips deserved better.

Blue Chips is not a masterpiece. But as I watched Nolte’s character sign his Faustian bargain, I understood why the film was panned. It goes back to what Shelton said about why his script didn’t sell: it’s not heroic. Blue Chips was not the narrative being pushed in the 1990s. It stood in direct opposition to the Clinton-era, “Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow” Boomer fantasy. Movies, especially those about sports, had happy endings. Rudy got to play for Notre Dame in the titular 1993 movie. The Sandlot, as iconic as it is to Gen X and older Millennials, feels like a charming relic from the early '80s. Like Field of Dreams and A League of Our Own before it, the message was baseball is good, we like baseball, therefore we’re good. That's what you got from sports movies in the late-'80s and early-'90s.

Not Blue Chips. It’s a movie about corruption in college basketball, but dig a few inches deeper, and you see it’s a film about rotting American values. Education is an afterthought when the scouts are talking, a nuisance they’ll figure out if they can sign the star athletes. Who cares if they’re dummies as long as they can dunk? The colleges either support the coaches cheating to get the top talent or turn a blind eye to it. The parents of the athletes also understand this is a business. When Nolte asks Alfre Woodward, who plays the mother of Hardaway’s character, what sort of man her son will become if he starts his adult life bending the rules, she replies, “a millionaire.” Whether they knew it or not, Shelton and Friedkin seem to be foreshadowing the everyone-sells-out influencer culture of the 21st century.

It's a cynical statement, and Blue Chips is a cynical film that tries to be entertaining. It sometimes is. At least by 1994 standards it was. That’s maybe why it didn’t work then. But watching it through a 21st century lens, it looks different. At the center of the movie is the message that people with money and power will break any rule to enrich themselves further. We see it play out constantly in 2023. In Blue Chips, J. T. Walsh plays Happy, the booster who is pressuring Coach Bell to “buy” big-name recruits with promises of money, cars, and homes. He’s the bad guy in the movie, a manifestation of all that’s wrong with the system. The players they’re trying to attract are from poor families and basketball is their ticket out of poverty. The college will make millions if they’re successful, the players would (hopefully) go on to big-money NBA contracts, and the NCAA would be none the wiser that some rules were broken. If there’s any fault I can find in Blue Chips, it’s that the movie didn’t lean more into that part of the story—how college sports was and remains a filthy business.

Roger Ebert was one of the few critics who liked the movie, and he understood what Friedkin and Shelton were trying to pull off. “The movie contains a certain amount of basketball, but for once here's a sports movie where everything doesn't depend on who wins the big game,” Ebert wrote. “It's how they win it. … What Friedkin brings to the story is a tone that feels completely accurate; the movie is a morality play, told in the realistic, sometimes cynical terms of modern high-pressure college sports. … The message seems to be that although one man can take a stand, the system has been too corrupt for too long to change.”

Eventually, a new generation that had read none of the bad reviews (nor would probably care about them) discovered Blue Chips. It is frequently counted among the best sports movies ever made and earned new accolades in 2019 when media outlets did 25th anniversary retrospectives. I hope Friedkin got to see that. The movie served as a bridge to more honest looks at American sports like Friday Night Lights, as well as a blueprint for better basketball movies, from Love & Basketball to Hustle. In 1994, audiences weren’t ready for a little honesty in their sports narratives. They wanted heroics, and Blue Chips doesn’t deliver. Instead, it was a once-great director burning another chance at box-office success to shatter the idea that everybody does it for the love of the game.

Blue Chips suffered because it was ahead of its time. Three years before the film, Jerry Tarkanian, the coach of the 1990 NCAA champion UNLV Runnin’ Rebels, resigned after a photo emerged of three of his players hanging in a hot tub with a man who had been convicted of fixing games. By the start of the new century, it was made public that Chris Webber and three other former Wolverines from the famed “Fab Five” University of Michigan squad had been given a total of over $600,000 by a booster. Today, college athletes can get paid to play sports. They can receive gifts from boosters and endorse products. It’s still hardly a fair system, but it’s tough to imagine any movement on the matter would have happened at all if the public had never learned about what goes on behind the scenes of college sports, and if a movie like Blue Chips hadn’t come out, wrapping up a deeper message in ‘90s basketball melodrama. It wasn’t a hit, but its unjaundiced glimpse into corruption in college sports helped educate the people who gave it a chance in 1994. Now it’s just time for everyone else to give it another chance.

You Might Also Like