Willem Dafoe Explains How 40 Years of Playing Gods and Monsters Primed Him for ‘Poor Things’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

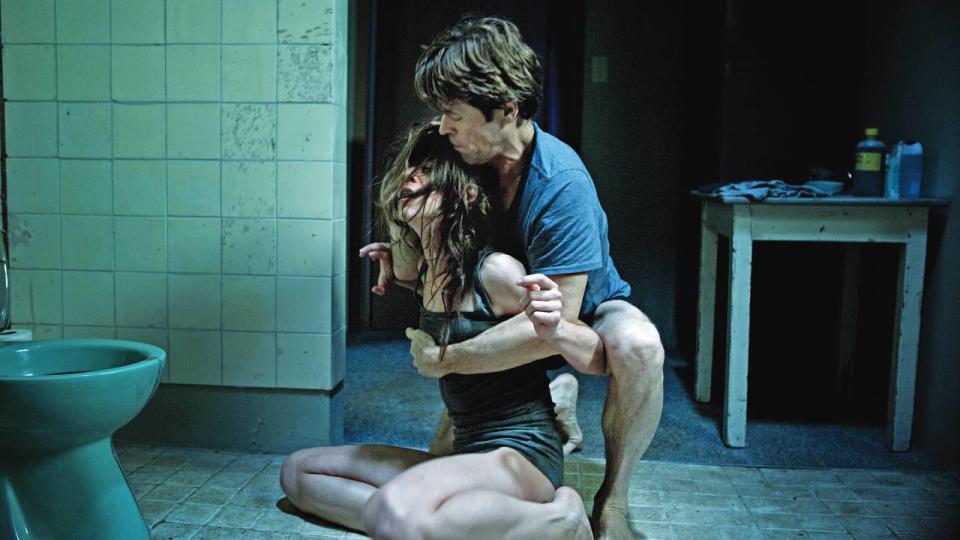

When Willem Dafoe receives his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame Jan. 8, the distinction will commemorate more than just a four-time Oscar nominee, but an actor so versatile that he has embodied everything from a conflicted messiah in “The Last Temptation of Christ” to the tortured father figure of “Antichrist.” Is there an actor working today with greater range?

With his deep-set eyes, sharp nose and broad smile, Dafoe has depicted his share of devils, from creepy “Nosferatu” star Max Schreck in “Shadow of the Vampire” to comic-book villain the Green Goblin in “Spider-Man 2.” But he also excels at the other end of the spectrum, as when he plays God in Yorgos Lanthimos’ “Poor Things,” a Frankensteinian surgeon charitably committed to reanimating dead creatures, like Emma Stone’s Bella.

More from Variety

“My character has this beautiful predicament, because he adores her so much and she adores him, but what she needs, he can’t give,” Dafoe summarizes, going out of his way to challenge those who might label his character a “mad scientist”: “That’s so wacky. He’s a damaged person, but he’s trying to do a good thing.”

Our career-spanning conversation began four months ago at the Toronto Film Festival, where Dafoe was one of the few actors allowed to attend and promote a project amid the actors strike. That would be “Gonzo Girl” — an independent production, directed by Patricia Arquette and covered by a SAG-AFTRA interim agreement — in which Dafoe is transformed into a gun-waving, acid-tripping kook clearly inspired by Hunter S. Thompson.

“I was a little haunted by ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’ and ‘Where the Buffalo Roam,’” he told me shortly after the film’s premiere. Johnny Depp and Bill Murray had already committed their versions of the gonzo legend to screen. “I didn’t want to get into some kind of thing where I’m imitating Hunter Thompson. We had to have some take on it,” Dafoe said then.

Turns out, rechristening the character Walker Reade, as former Thompson assistant Cheryl Della Pietra had in the novel the film is based upon, gave Dafoe room to invent. Instead of feeling obligated to shave his head and become the larger-than-life writer, he could do his research and distill whatever traits resonated with him. “You do the stuff that feels like it helps you to tell the story, and the stuff that you can’t or don’t want to do, you let it go,” he says.

Talking to Dafoe in Toronto (and again months later via Zoom once the strike had ended), his strategy for picking roles became clear. “I’m always driven by directors,” he explains, citing his respect for artists who are quite literally “seized by visions.”

Just look at his filmography. In addition to Martin Scorsese and Lars von Trier, he’s worked with such visionary auteurs as David Lynch (“Wild at Heart”), Wes Anderson (“The Grand Budapest Hotel”), Abel Ferrara (“Pasolini”) and Guillermo del Toro (“Nightmare Alley”), to name but a handful.

“I need someone that I feel has an overview that I trust, and I can kind of take a jump off a cliff,” says Dafoe, who began his screen career working on — and eventually being fired from — Michael Cimino’s “Heaven’s Gate” as a background performer. The director had just won the Oscar for “The Deer Hunter,” and though the ever-lengthening production took Dafoe away from the Wooster Group, the avant-garde New York theater company to which he was dedicated, “I was just happy to be there in any capacity,” he says.

Three months into the production, at the end of a long day of sitting around for hours in costume and makeup while Cimino tinkered endlessly without shooting, someone leaned over and whispered a dirty joke in Dafoe’s ear. He laughed, and Cimino immediately ordered him off the set. Confused, the actor returned to his hotel, where an assistant handed him a plane ticket home. “Years later, Cimino asked me to do something. We talked, and he sort of apologized, and I forgave him. But it was humiliating,” he recalls.

Dafoe continued to focus his energy on the Wooster Group, where he worked seven days a week. It was there at the SoHo performance space that he met experimental director Elizabeth LeCompte, who was his partner for more than a quarter century.

“We’d rehearse stuff in the afternoon and perform it at night,” Dafoe says. “Sometimes it was very difficult because you didn’t get a chance to refine it. But it taught you not to wait, not to be precious, and just to throw yourself into it.”

With such roots, it’s no wonder Dafoe responds to situations where directors create the world and turn him loose. “There’s a part of me that’s in it for adventure. I want to be a little irresponsible, and I want to have something happen,” Dafoe says.

The role that really made a difference for Dafoe was Sgt. Elias in “Platoon” — a low-budget Vietnam movie from an unproven director, Oliver Stone, starring a cast of mostly unknown actors (many of whom went on to be huge stars), in which Dafoe plays the moral compass in an upside-down war. Until that point, Dafoe had identified as a stage actor. But that performance earned Dafoe his first Oscar nomination. “Then I thought, ‘OK, maybe I can do this,’” he says.

Knowing he could always go back to underpaid theater work, Dafoe felt he could be selective about his roles. In 1988, starring in two vastly different projects, he played an FBI agent investigating a civil rights case in “Mississippi Burning” and Jesus Christ in Scorsese’s controversial “Last Temptation.”

The latter role cost him work — both then and many years later — from producers unwilling to cast the man who’d dared to play Jesus. But it made him top of Lanthimos’ list for the role of God in “Poor Things.”

Godwin Baxter is a damaged person, experimented on by his own father, as reflected in the elaborate mask Dafoe wears in the film — just one of the many tools director Lanthimos gave Dafoe to work with. In the veteran actor’s experience, shaped over a career of more than 100 film credits, Dafoe finds that most filmmakers have an emphasis. Some are born “shooters,” specializing in the image, while others love working with actors, or excel at the script level.

“Yorgos is a full package,” Dafoe says. “He’s a polymath who works with all the departments in a very integrated, hands-on way. He makes a world that’s so specific and particular that when you enter it, it gives you so much, because it doesn’t elicit normal responses.”

When Dafoe finds a filmmaker who challenges him in exciting ways, he’s quick to sign on for another collaboration (he’s made seven films for director Paul Schrader and reteamed with “The Lighthouse” director Robert Eggers on next year’s “Nosferatu”). As soon as “Poor Things” wrapped, he and Stone turned around and made another film with Lanthimos, tentatively called “Kinds of Kindness.”

“There’s a tendency, particularly when people get older, that they refine their impulses and like to work a certain way and don’t like to jump around,” says Dafoe, who prefers to mix it up. For example, he followed studio sequel “Speed 2” — “I don’t take back that performance,” he volunteers — with a risky art film.

“It’s like planting seeds in different places,” he says. “Do you plant a monocrop, where you’re waiting for that one thing to grow? Or do you plant many different things so that when you least expect it, opportunities arise, and you always have a certain variety?”

Best of Variety

From 'Killers of the Flower Moon' to 'Eileen': The Best Book-to-Screen Adaptations to Read This Year

The Best 'Sopranos' Merch to Celebrate the Show's 25th Anniversary

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.