Who will pick up Kennedy's bipartisan legacy on the court? No one.

WASHINGTON — Josh Blackman, the libertarian legal scholar, was at the U.S. Supreme Court on Tuesday morning to watch the final day of the 2017-2018 session, when, around 8 in the morning, Mary Davis Kennedy, wife of Supreme Court Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, walked into the chamber with what looked to Blackman like several of her children and grandchildren.

“Oh f***,” someone near Blackman uttered. The long-rumored retirement of Kennedy, who has been the deciding vote on the divided court, seemed finally at hand. After the court finished its business, Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. announced that there would indeed be three retirements — of Supreme Court employees, not justices.

“False alarm,” Blackman tweeted.

But the alarm was not false. In a letter to “My dear Mr. President,” Kennedy gave “a respectful and formal notification” of his retirement, effective July 31 — and thereby offered President Trump the opportunity to name a second justice to the high court after just a year and a half in office. The announcement set off furious speculation about who that pick would be, as well as a bipartisan appreciations for Kennedy, who in his 30 years on the court sometimes sided with the court’s liberals and at other times with its conservative bloc, refusing to adhere to a dogmatic legal philosophy.

“Justice Kennedy was the justice most likely to look at each case with fresh eye,” says Orin Kerr, a professor of law at the USC Gould School of Law in Los Angeles. “It’s the end of an era,” a stunned Kerr said, when he learned of Kennedy’s retirement from Yahoo News. Kerr, who clerked for Kennedy in 2003 and 2004, added that Kennedy was “a terrific boss. Very generous, kind and patient. A great person to work for.”

Kennedy, who was nominated by President Ronald Reagan, was a genuine maverick, uniquely capable of infuriating both Democrats and Republicans who wanted to use the courts to advance their agendas. He handed conservatives a major victory in 2010 with his vote on Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which effectively opened political campaigns to largely unrestricted involvement by unions and corporations.

But in 2015, Kennedy was “hailed as a gay rights icon,” as Politico put it, for his vote in Obergefell v. Hodges. Writing with compassion, context and depth, Kennedy argued that same-sex couples deserved to join in the legal bond of marriage. “The nature of marriage is that, through its enduring bond, two persons together can find other freedoms, such as expression, intimacy, and spirituality,” he wrote. “This is true for all persons, whatever their sexual orientation.”

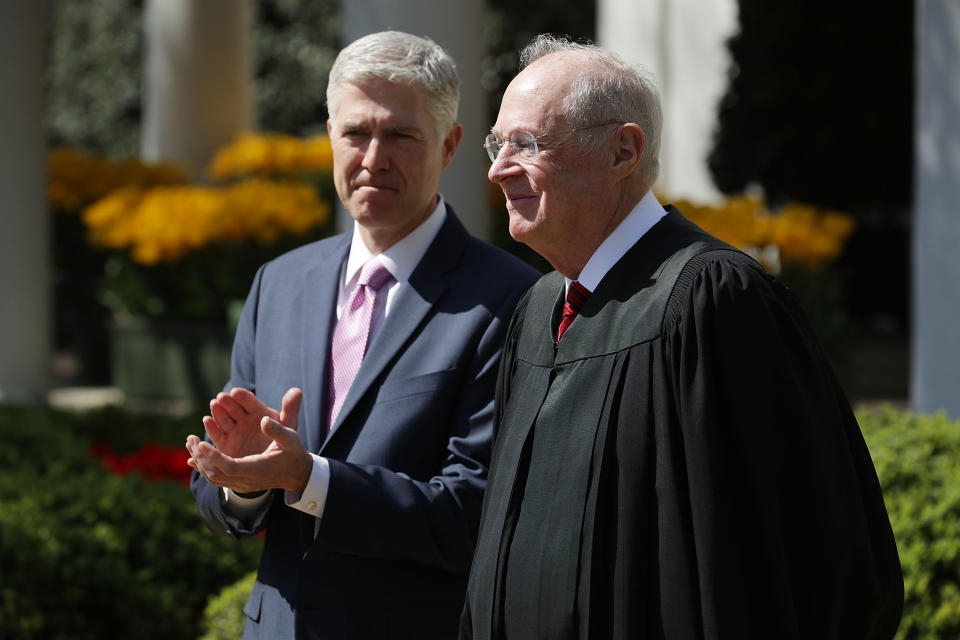

“Justice Kennedy is a famously complicated person with a strong libertarian streak in his views,” says Andrew M. Grossman, a constitutional expert at the Washington, D.C., firm of BakerHostetler, who has submitted a number of briefs to the Supreme Court. Grossman told Yahoo News that Kennedy “lived and breathed the Constitution.” But unlike the strict originalists on the bench — notably, Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, who was Trump’s first nominee — Kennedy ruled “in the common law tradition,” studying the way laws not only originated, but how they evolved.

“The broadest part of Justice Kennedy’s legacy stands to live on,” said Grossman, a former fellow at the Heritage Foundation. The nation’s most prominent conservative think tank, Heritage has played an influential role in guiding Trump’s judicial appointments. For its part, Heritage chided Kennedy for his “breathtaking inconsistency” in a statement issued by the foundation’s vice president, John Malcolm.

Political opponents of Malcolm may agree with that assessment. Elisabeth Semel, who heads the Death Penalty Clinic at Boalt Hall, the law school at the University of California at Berkeley, told Yahoo News that she was disappointed that Kennedy “never came to the table on capital punishment.” She cited, in particular, his siding with the conservative majority in Glossip v. Gross, the 2015 case about whether the use of lethal injection for the death penalty constituted cruel and unusual punishment.

“I had hoped that he would come farther than he did,” Semel says, wondering why same-sex couples deserved nuanced considerations about human dignity but prisoners on death row did not. “You don’t pick and choose who gets human dignity,” she said.

Kennedy’s decision to stand alone, between the court’s increasingly warring factions, exposed to him to relentless criticism, even as lawyers tailored their arguments to appeal to his predilections. Robert Barnett, a partner at Williams & Connolly, recalled clerking for Supreme Court Justice Byron White, who was similarly regarded as the court’s “fifth vote.” In an email, Barnett praised Kennedy for “his intelligence, his restraint, his foresight, his hard work, his understanding of the importance of his role, his leadership, and (as a former clerk) how he treated those who worked for and learned from him.”

Trump’s nominee for Kennedy’s seat is certain to hew more closely to conservative orthodoxy, and could cast the critical vote on issues that include gun rights, abortion and congressional reapportionment. And though Democrats are the minority party on Capitol Hill, they are promising to mount a furious opposition campaign.

“This will be,” Barnett predicts, “one of the most consequential appointments in my lifetime.”

(Cover thumbnail photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

_____

More Yahoo News stories on Anthony Kennedy’s retirement