How ‘Wild Life’ Protagonist Kris Tompkins Overcame Grief To Accomplish Something Incredible For The Planet

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

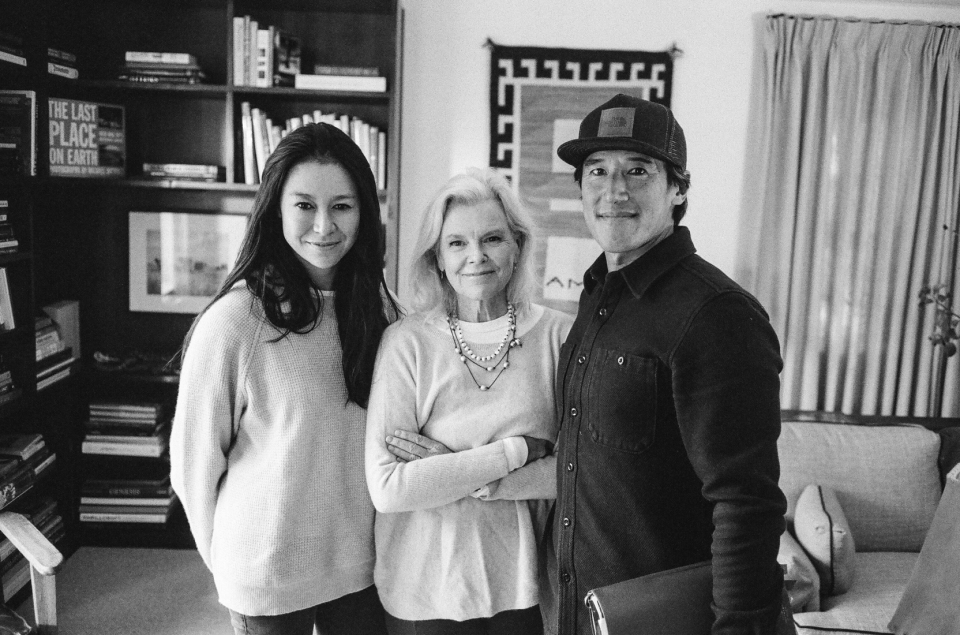

The filmmaking couple Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin have earned a reputation for making documentaries about people who accomplish the unthinkable – the no-ropes climber Alex Honnold in the Oscar-winning Free Solo, or the divers of The Rescue who, against all odds, saved a group of Thai kids stranded in a flooded cave.

As it happens, the heroes of their best-known films have been men, but in their latest documentary, Wild Life, the focus shifts in large part to a woman, the conservationist and former Patagonia CEO Kris Tompkins.

More from Deadline

“It was really nice to make a film where there’s a woman at the center,” Vasarhelyi remarked at CPH:DOX in Copenhagen, where the film screened last month. Wild Life, from National Geographic and Picturehouse, just expanded to theaters in Southern California, including Los Angeles, as well as the San Francisco Bay area after opening in New York and DC last weekend.

The documentary tells the love story of Kris and her late husband Doug Tompkins, founder of The North Face and co-founder of retailer Esprit. They met in mid-life at a time when Doug had given up his companies for a life in the wild terrain of remote Chile and Kris also found herself yearning for a radical change of existence. Together, they began acquiring land in Chile and Argentina on a massive scale – not for their private enjoyment, but with the goal of turning it over to those countries for the creation of vast national parks.

In the film, Kris reads from her journals about being with Doug in Chile. “I feel the memories of nearly 20 years in this valley. Years of joy, pain, doubts, and reassurance… Few have lived as we have here.”

In conversation with Deadline, Kris Tompkins conceded it took some convincing to get her to agree to the documentary – but perhaps not for the reasons one might expect. She says instead of hoping to project an idealized image of herself, she wanted to make sure the film felt unvarnished.

“I didn’t want it to be some sort of fluff piece. I’d hope that it was very candid,” Kris tells Deadline. “I gave them everything — 26 years of journals, all the photography, everything. Once I was in, I was all in. But it took me a while to decide.”

Wild Life explores the arduous process the Tompkins went through to convince the governments of Chile and Argentina that their motives were pure and they weren’t trying to gobble up land as part of some nefarious scheme that would jeopardize those countries’ national security. Along the way, the couple faced death threats and covert surveillance by shadowy antagonists.

“Probably four or five years into getting started in Chile, someone sent me a book on the history of the creation of the Grand Teton National Park [in Wyoming]. And I realized that took something like 50 or 60 years to create, and it was truly a gun-slinging process,” Kris notes. “And I thought, God almighty, if I had just read the history of most national parks so long ago, we would have understood so much more — one, how to deal with the threats and everything that was happening to us, but also be prepared that, no matter where you are, this kind of conflict is inherent and it’s going to take place.”

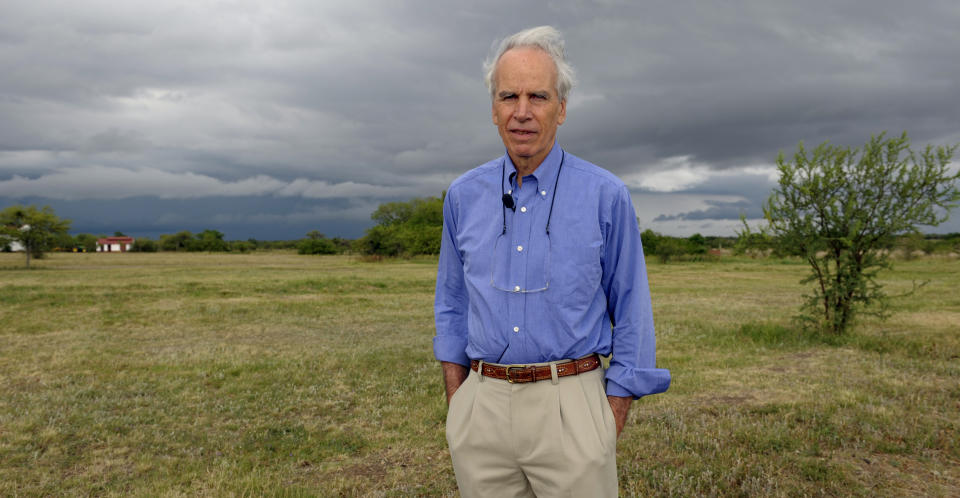

A tragic event almost sundered the immense conservation project. In 2015, Doug embarked on a kayaking trip on Chile’s Lake General Carrera with a group of friends, including Yvon Chouinard, founder of the Patagonia outdoor brand, and Rick Ridgeway, a climber and filmmaker. Gusting winds kicked up huge waves, and the kayak Tompkins and Ridgeway were in capsized in the frigid waters. Ridgeway survived, but Doug succumbed to severe hypothermia.

Rick Ridgeway, a longtime friend of co-director Jimmy Chin, appears in the film and shares his recollection of that fateful day.

“There was an interview that we did in Patagonia, near that lake where Doug died, where we had our accident. And that was difficult because I did have to relive it,” Ridgeway tells Deadline. “While it was emotional, I didn’t have any caution about reliving it in front of the camera with Jimmy behind the camera… Jimmy and I are such close friends and I’ve been out in the field with him in a lot of really tough circumstances.”

At a talk in Copenhagen, Chin recalled, “There were a few interviews where we had to stop because the entire crew was crying. Like, certainly, a few interviews with Kris early on when Doug’s death was still very raw and she was kind of just giving it up to us. And it was really hugely emotional.”

Immediately after Doug’s death, Kris found herself at a crossroads – whether to be consumed by shattering grief or to move forward with the work of creating the national parks. As the film shows, she summoned the strength to go on. The vision of creating national parks has become a reality, and because of the ongoing work of the nonprofit Tompkins Conservation almost 15 million acres of pristine wilderness in Chile and Argentina are protected in perpetuity.

Today, Tompkins Conservation devotes itself not only to preserving wild lands but to reintroducing species native to those habitats, animals that have been pushed towards extinction.

“When we bought the first property in 1997 in Iberá, in northeastern Argentina, almost every [creature] was missing, from the jaguar all the way down,” Kris says. “That’s when we really made a commitment and it changed our work forever… It’s half of our work at least now, is working with extirpated species.”

Tompkins, Ridgeway and Patagonia’s Chouinard joined the filmmakers for a screening of Wild Life earlier this month at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. A few months ago, Chouinard announced he would turn ownership of Patagonia over to a collective, with all profits donated to fight climate change, protect wilderness and preserve biodiversity.

“The film inspires people to follow in Kris and Doug and Yvon’s footsteps, but that doesn’t mean that you have to create new national parks or give away your 3 billion company to the planet Earth,” Ridgeway comments. “We are hopeful the film inspires people to, as I said to the audience [in New York], use whatever tools are in your box. As climbers say, you’re never gonna make the last step until you make the first step. And you gotta commit. And as Doug always said, commit and then figure it out. But commit. Make that step.”

Ridgeway added, “That doesn’t mean that we’re all wealthy enough to be philanthropists, but we can all get involved in supporting the groups on the ground, doing the work, the hard work to save wild lands and wildlife. And they all need help. They all need volunteers.”

Kris Tompkins says she’s keeping her focus on the future.

“We want our legacy to be rewilding Chile and rewilding Argentina. And those are the people we worked with for decades,” she says. “And because Doug died and because I’ll die at some point — we know that — I made [these initiatives] both independent… So, in my book, that’s our legacy — not so much what we’ve done in the first 30 years, but what’s going to happen in the next 50 years with the second generation and third generation of people.”

Best of Deadline

Hollywood & Media Deaths In 2023: Photo Gallery & Obituaries

2023 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.