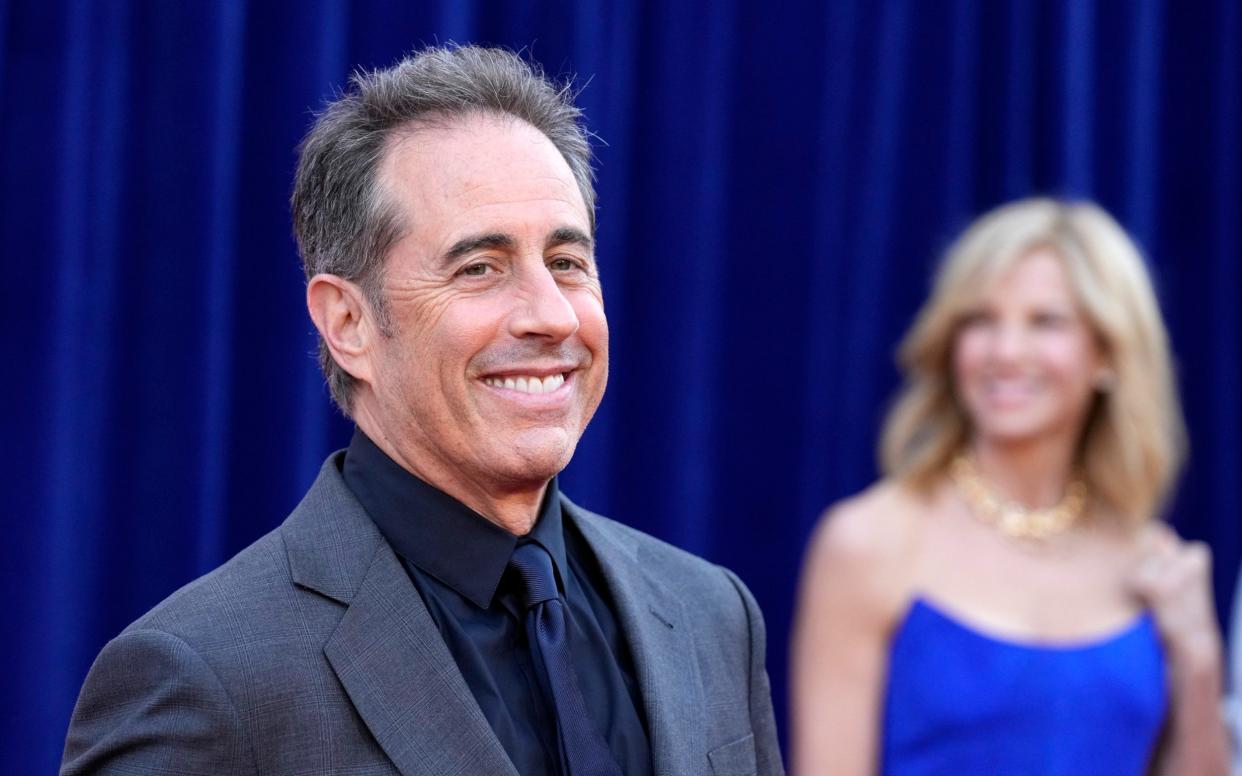

Why the world stopped laughing at ‘tone-deaf rich guy’ Jerry Seinfeld

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The developments at Duke University last weekend could almost have come from Curb Your Enthusiasm, the show that famously arose from Jerry Seinfeld’s eponymous Nineties sitcom. American universities have a habit of inviting a celebrity or leading figure in their field to deliver a commencement address to their students as they graduate, and, on paper, few are more distinguished than Seinfeld, one of comedy’s few billionaires whose achievements are unmatched within his field.

Yet, as he was about to deliver his speech, dozens of students simply walked out, booing loudly as they departed. Others remained, but unfurled ‘Free Palestine’ flags, and hurled abuse at the comedian as he delivered his address. Amidst cries of “Disclose, divest, we will not stop, we will not rest”, Seinfeld – who, one imagines, had seldom had such a vitriolic reaction since his early days on the comedy circuit – delivered a would-be inspirational speech in which he urged his listeners to work hard, listen to those wiser than themselves and find someone to grow old with.

“Whatever you’re doing, I don’t care if it’s your job, your hobby, a relationship, getting a reservation at M Sushi, make an effort,” he said. “Just pure, stupid, no-real-idea-what-I’m-doing-here effort. Effort always yields a positive value, even if the outcome of the effort is absolute failure of the desired result. This is a rule of life. Just swing the bat and pray is not a bad approach to a lot of things.”

The cause of the protests was Seinfeld’s support for Israel in its war against Hamas. In a recent interview, he claimed that “the struggle of being Jewish is somewhat ancient…[there have been] thousands of years of struggle, and Israel is the latest one…antisemitism seems to be rekindling in some areas.” He visited the country at the end of last year, and expressed his support for them in the current situation, telling the Times of Israel that he would “always stand with Israel and the Jewish people”; something guaranteed to infuriate the pro-Palestinian sector of America’s student population. Hence the rather less than welcoming response at Duke, where, ironically, two of Seinfeld’s own children studied.

Had this been an isolated incident, it would have been easy to dismiss as little more than a piece of performative rudeness orchestrated by a gang of attention-seeking rabble-rousers. In any case, he could hardly have been surprised by the reaction, given that, as far back as 2015, Seinfeld had advised his fellow comics not to perform at university campuses. But the comedian has not exactly been winning fans in recent months, ever since he began his publicity campaign for his new Netflix comedy, Unfrosted. The film, which explores the creation of Kelloggs’ Pop-Tarts in the Sixties, not only starred Seinfeld, but was directed, co-written and co-produced by him as well.

It should have been an enjoyable piece of light relief, but instead launched on the streaming service to some of the worst reviews that any picture has had in living memory, to say nothing of disappointing viewing figures. It may have been Netflix’s no 1 movie, but its 7.1 million views were about a third of what the service usually obtains for its new releases in their opening week. As Richard Roeper put it in the Chicago Sun-Times: “Unfrosted is one of the worst films of the decade so far.”

It is not hard to see why Unfrosted failed. It is less a coherent motion picture than a series of not particularly funny sketches, which allows Hugh Grant to desecrate the sacred memory of Paddington 2’s Phoenix Buchanan with a lukewarm reprise of that great role as Thurl Ravenscroft, a disgruntled Shakespearean actor earning a crust by voicing the company’s mascot Tony the Tiger. On paper, it should be funny, but on screen, despite Grant’s best efforts, it’s bewilderingly flat and tedious.

Seinfeld, clearly aware that his directorial debut was less Citizen Kane and more Citizen Khan, maniacally threw himself into promotional duties. He even satirised this when he appeared on Saturday Night Live, introduced as “the man who did too much press”.

Yet whether out of exhaustion, boredom or a septuagenarian’s desire to provoke, Seinfeld has been offending those on both sides of the political divide. He may have sneered at Donald Trump, calling him “God’s gift to comedy”, but in widely reported remarks that he made on the New Yorker Radio Hour podcast, the comedian also declared that the recent downturn in scripted comedy was “the result of the extreme left and PC crap, and people worrying so much about offending other people.”

Warming to his theme, Seinfeld declared that “When you write a script, and it goes into four or five different hands, committee groups – ‘Here’s our thought about this joke’ – well, that’s the end of your comedy.” This may have sounded clever as he said it, but not only ignores the consistently outrageous likes of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia and, indeed, Curb Your Enthusiasm, but also suggests that this billionaire has been spending far too much time talking to his wealthy peers – as he so famously does on his Netflix series Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee – and not watching TV.

In the same podcast, Seinfeld said that he felt a degree of freedom in being a stand-up comedian rather than a creator of a show such as his eponymous sitcom. “With certain comedians now, people are having fun with them stepping over the line, and us all laughing about it,” he said. “But again, it’s the stand-ups that really have the freedom to do it because no one else gets the blame if it doesn’t go down well. He or she can take all the blame [themselves].”

One of the mantras of the sitcom Seinfeld was “no hugging, no learning”; the characters in it were believably flawed, and stayed that way, and, in contrast to the far more touchy-feely likes of Friends and (eventually) Frasier, there was to be no moment where the show’s protagonists learnt to become better people. So it proved with Seinfeld himself, when, after delivering his apology at Duke, he had his very own ‘je ne regrette rien’ moment. “The slightly uncomfortable feeling of awkward humour is OK,” he declared. “It’s not something you need to fix… I may not have calibrated that perfectly, but I would not change it.”

Had he not been surrounded by booing and baying students, Seinfeld’s point might have seemed to be an elegant and nuanced one. The freedom to cause offence is one that not only draws on America’s first amendment-protected rights of free speech, but also underpins every facet of comedy, from the works of Aristophanes and Chaucer to anyone putting jokes on YouTube or social media today. Yet the problem remains that Seinfeld himself now looks hopelessly out of touch, sequestering himself away in vast apartments in Manhattan and mansions in the Hamptons, where he keeps a classic car collection of over 150 vehicles that is said to be worth over £80 million.

In many regards, Seinfeld’s post-sitcom career has been the exact opposite of his near-contemporary Kelsey Grammer, who has struggled to find a role as iconic as that of Frasier Crane. Seinfeld could hardly be described as reclusive, but he has seldom acted in others’ projects, save for self-mocking cameos as himself, and his appearance in Unfrosted is notable for being the first time that he has portrayed another (non-animated) character on-screen in a leading role.

Instead, what seems to drive him is spending his days writing jokes, which he then performs at unassuming comedy clubs: a process detailed in his 2002 documentary Comedian, which was released shortly after his sitcom came to an end in 1998. The film may have one of the funniest trailers ever made, but, perhaps unwittingly, it’s also an acute glimpse into the psyche of a man who wants to have his cake and eat it.

Seinfeld claims to value the cut and thrust of being on stage in front of audiences who treat him the same way as any other performer, but no other performers in such venues have the luxuries of private jets, multiple expensive residences all over the world – complete, if the rumours are accurate, with a $17,000 coffee maker – and well-paid PR staff on hand to flatter his considerable ego at all times.

One of the reasons why the Duke appearance may have been so upsetting for Seinfeld is that he is, in many regards, identical to the ‘Jerry’ persona that he displayed in his sitcom for over a decade: uptight, misanthropic and cynical. For someone who could, theoretically, been at the top of the A-list, he is a curiously detached presence in the entertainment industry.

A 2018 video that went viral showed Seinfeld, mid-red carpet interview, being approached by the singer Kesha, who fawningly asked him for a hug; he briskly refused, edged away from her, and commented “I don’t know who that was”. Once told that she was not a deranged fan but a fellow attendee of the event, he dismissively said “Well, I wish her the best.” Kesha, for her part, later described the snub as “the saddest moment of my life”, given that Seinfeld was one of her comic idols.

That Seinfeld was one of the great comedic innovators, performers and writers of the past half-century cannot be repeated enough. Many of the catchphrases from it – “No soup for you!” “Not that there’s anything wrong with that” – long ago entered the common lexicon and are cited and quoted by TikTok users who were not even born when the show ended.

The man whose sitcom was bought by Netflix for $500 million in 2021 remains big business, even if his attempts to remain relevant have attracted criticism; his last stand-up special for the streamer, 23 Hours to Kill, was ridiculed by Fast Company as “more tone-deaf, rich-guy humour, told in the exact same style he’s been using since the moment he became a famous comedian about 40 years ago.” Dare one ask whether the angry mob at Duke should have been complaining less about Seinfeld’s political stances and more about how he seems to have forgotten the art of being funny?

Seinfeld has long since passed the point of ever needing to think about making money any longer. He could self-finance a dozen Unfrosteds, if he wished to inflict such a continual torment upon the world. Yet he is sufficiently intelligent not to repeat such mistakes. Had the Duke students listened to his speech, rather than angrily protested, they might even have noted that he spoke a great deal of sense when it came to the everyday value of humour.

“I need to tell you as a comedian, do not lose your sense of humour,” Seinfeld said. You can have no idea at this point in your life how much you’re going to need it to get through. Not enough of life makes sense for you to be able to survive it without humour.” He concluded with a piece of uplifting wisdom: “Even if it’s at the cost of occasional hard feelings, it’s okay, you gotta laugh.”