How Postwar Japanese Director Yasuzo Masumura Came to Be the Biggest Breakout at Karlovy Vary

At a festival the size and stature of the Czech Republic’s Karlovy Vary, new discoveries are a daily occurrence. But it is rare that at festival’s end, one of the most excitingly buzzy emergent names should be that of a filmmaker who died 37 years ago and who has languished in relative obscurity – certainly in the Anglophone world – ever since. And yet here we are, at the tail end of an 11-film Yasuzo Masumura retrospective – the biggest of its kind ever mounted at an international film festival – that has proved, in a word, revelatory.

It’s not just in terms of blowing the dust from this extraordinary, unjustly overlooked filmmaker’s catalog, but also in the broader sense of being an exemplary model for how to connect a vibrant, youthful regional audience to global film history. There is a classic film fan born every minute, but in Karlovy Vary this year, you could feel it happen in real time during the screenings of Masumura’s “A Cheerful Girl” (1957), “Hoodlum Soldier” (1965), “Spider Tattoo” (1966) and so on.

More from Variety

The selection, curated by Karlovy Vary programmer Joseph Fahim, represents only the tip of the 60-title iceberg of Masumura’s filmography and is remarkable for how, across nearly a dozen features, the director so rarely repeats himself. Encompassing the melodrama, satire, buddy comedy, erotica, exploitation, courtroom, espionage (industrial and political), coming-of-age and romance genres, presented in crisply restored widescreen black-and-white and gorgeously punchy, vivid technicolor, the program is diverse, but never less than wildly entertaining.

As such, it feels like Fahim has hit on a kind of retrospective Holy Grail, but the story of it started in a car journey en route to the Venice Film Festival last year with Karlovy Vary artistic director Karel Och. “Karel drives and I just tag along from Prague to Venice,” Fahim tells me as we sit on the terrace of the Thermal Hotel amid the happy hubbub that drifts up all day and most of the night from the outdoor bars in the park beyond. “We talk about everything in our lives and then we reach a point where we’re bored out of our minds because it’s nine hours, and Karel has to stay awake. So it’s like what to talk about now? Let’s talk about retrospectives.”

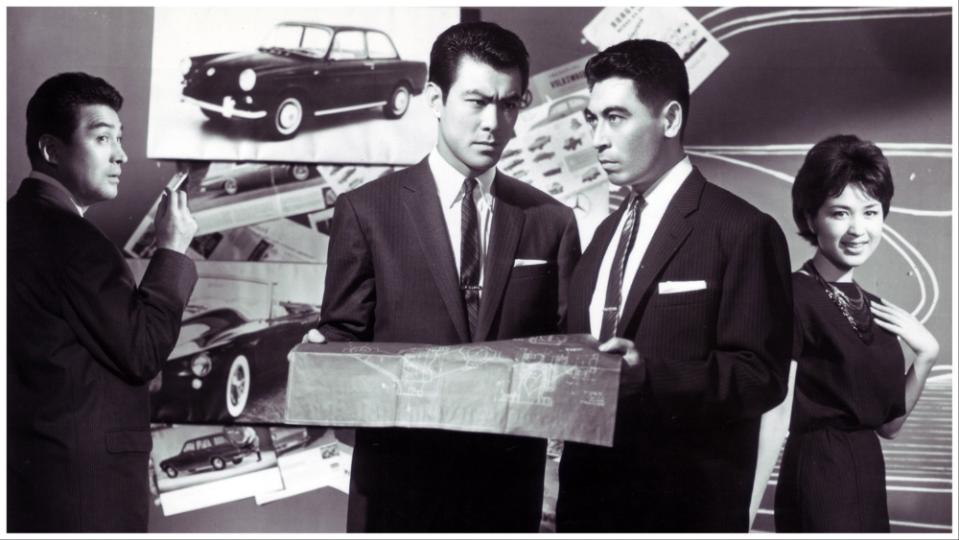

“Just before Venice last year I had watched two Masumura films: ‘The Black Test Car’ and ‘Giants and Toys,'” he continues. “And then, quite by coincidence, we discovered that next year is Masumura’s centenary. We thought, probably there’s going to be a rediscovery of this guy, so we should do it before everyone else does. So I just want to say, on the record, next year when everyone’s doing Masumura retrospectives – we did it first!”

Fahim is joking but there is a palpable sense on the ground that Karlovy Vary has earned the right to the association. “The guy has never got much attention – there was a Cahiers interview long ago and [critic] Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote a piece on him in the late ’90s – but because of the lack of literature there is still so much to unpack and uncover about him,” says Fahim. “There are still some films of his that I haven’t been able to get hold of, and I am dying to see.”

Of course, the key question is why Masumura has remained under the radar for so many, for so long. “Unlike Kurosawa, unlike Mizoguchi, Oshima and Imamura, his movies were not travelling outside Japan, and so he was simply dismissed,” says Fahim. “What I can’t fathom is why someone like [Seijun] Suzuki who is also very genre, very cool, also dealt in exploitation elements, why was he a lot more famous?… Masumura’s politics were just so pointed, he has such visual style and there’s a very strong philosophy behind each film, whether it’s about the militarization of Japan or women’s relationship to sex, or sex as a tool of individualization… I feel that neglect says more about the prejudices of film culture and film academia than it does about the films.”

It’s certainly true that the movies themselves are cinephile heaven, packing in a great deal of subtext and context but remaining, as the packed houses at the festival have attested, endlessly accessible. How has Fahim, who also curated the last two big Karlovy Vary retrospectives, managed to land on such a successful formula for promoting often obscure films to the general Karlovy Vary audience? He shrugs in wonder. “Look, we didn’t expect to have the success we did with the Youssef Chahine and World Cinema Foundation retrospectives. The Karlovy Vary audiences are just open to new things – it has happened with every single retrospective we’ve done. There’s a great hunger for discovery here. Really, I think there are few places in the world like it. And also there is something very contemporary about Masumura, very accessible, and our audiences are perceptive and smart enough to respond to that.”

It has to have been gratifying for the Kadokawa Corporation, the rights holders who have supplied Karlovy Vary with all the prints, many of them in pristine, newly restored form. “We got lucky with Masumura and the Japanese,” confirms Fahim, “because they really know how to take care of their films.” “It’s not that we wanted to steal the momentum from everyone else,” Och demurs to me later in reference to next year’s anniversary. “Kadokawa suggested themselves that Karlovy Vary would be the launching pad for a retrospective that they hope will go wide next year. And – with a representative here who has attended all 33 of the screenings all the way through – they have been really satisfied with the way it has been promoted and attended.”

Prior to that car journey, Och himself had never seen any Masumura films. “Joseph made the whole programming team watch several of his movies throughout the year and we all just fell in love,” Och says. “It was a whole world we had never been aware of. I mean, how can a film about two car companies fighting for a prototype [‘The Black Test Car’] be that exciting and that complex? Masumura is proof that mainstream cinema can be so progressive and bold.”

For Och, the impressive audiences are a result of a more than a decade’s groundwork. “I felt there was a hole in the market in 2004/5 when I took over the retrospective strand. We started off with Sam Peckinpah and John Huston and Cassavetes, for which we also brought sizeable delegations and related celebrities. And it started to send the signal that classic films are celebrated in Karlovy Vary, long before Joseph joined the band, with his vast knowledge of cinema that is not the usual suspects.” A festival’s classic focus can be “like a lighthouse,” Och says, recalling the “humbling moment when the Institut Lumière in Lyon contacted us about our Larisa Shepitko retro. Then we knew we were really part of a circle of festivals and cinematheques that we really admire, to which we can make our small contribution.”

Having had this level of success with something so apparently out of leftfield, how does Och see the future of Karlovy Vary’s classics segments shaping up? “It’s easy to get excited about being a place that ‘discovers’ something,” he muses. “But we have to be careful not to expand it too much at the expense of all our other sections – that could be the death of it. Still, probably next time, it’s not going to be another Milos Forman tribute, much as we love him, because that is now just too expected. And so I just look forward to another drive to Venice with Joseph…”

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.