Why Louis Armstrong is as American as July 4, his unofficial birthday

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Born on the Fourth of July." Many have made that yankee doodle boast — including songwriter George M. Cohan (born July 3) and MGM chief Louis B. Mayer (born July 12).

But Louis Armstrong is a special case.

For one thing, he seems to have really believed it. As far as he knew, he was born July 4, 1900. "It's what his mother told him," said Armstrong biographer Ricky Riccardi.

"He would say, 'My mom called me a firecracker baby.' " Riccardi said.

For another thing, Armstrong, alias "Satchmo," alias "Satchel Mouth," alias "Pops" — as he's variously known to his legion of fans — unquestionably should have been born on the Fourth of July.

"America is Louis Armstrong, and Louis Armstrong is America," said Riccardi, director of research collections at the new $24 million Louis Armstrong Center in Queens, which cut the ribbon just this past week.

Happy un-birthday

In fact, Louis seems to have been born on Aug. 4, 1901 — at least according to a baptismal certificate unearthed after his death. But for many jazz fans, July 4 will always be Satchmo Day.

"People associated Louis Armstrong with July 4," Riccardi said. "Whenever he was playing that day, the crowd would sing 'happy birthday.' "

WKCR FM 89.9, Columbia University's station, has been doing July 4 Louis Armstrong Birthday Broadcasts — all Armstrong, all day — since 1971 (Louis apparently heard the first one, two days before his death on July 6). When the Aug. 4 date was uncovered, the station simply started doing a second one.

"July 4 is the only date he knew, the only date he believed," Riccardi said. "So we call it the Traditional Birthday."

If anyone is important enough to have two birthdays, it's Satch.

"I think every jazz musician, every jazz fan, every lover of 20th century pop music should say thank you to Louis Armstrong for being born," Riccardi said.

The jazz world's latest thank-you is the new, sleek, grand piano-shaped Louis Armstrong Center in Corona, Queens, which opened June 29 (a trumpet-shaped building might have been an architectural bridge too far).

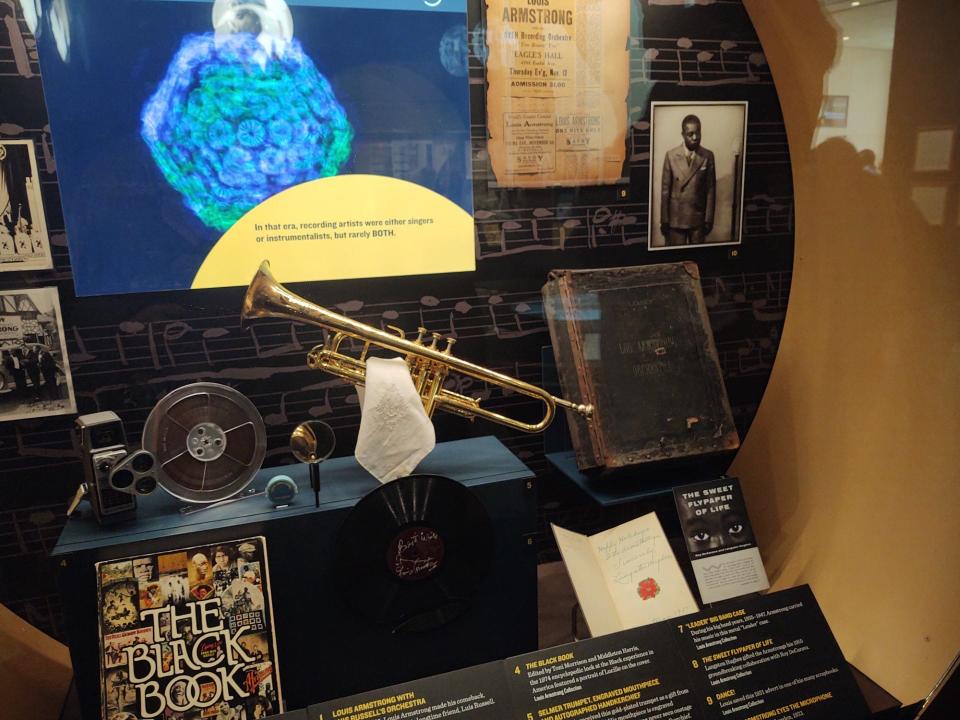

Here, under glass, you can see one of Louis' trumpets, his "Hello, Dolly!" Grammy, his reel-to-reel tape recorder, his books and sheet music and the collages he made in his spare time. Here, visitors can listen to live music in a 75-seat performance venue.

And here, too, scholars can now find the Louis Armstrong archives, moved from its original home at Queens College.

And people do research Armstrong. Lots of them.

Key figure

He is now widely recognized, not just as a beloved trumpeter and singer, not just as an important jazz figure, but as one of the key architects of American — and possibly world — culture.

"I think 50 years from now, when people ask who are the great figures of Western civilization, it's going to be Shakespeare, Mozart, and Louis Armstrong," Riccardi said. "And no one's going to question it."

It was Armstrong, launching his career in early 20th century New Orleans and Chicago, who freed American music from the yoke of European stiffness.

He taught music to swing. He invented the solo. He taught musicians how to play their instruments, vocalists how to vocalize, scatters how to scat.

His tremendously influential Hot Five and Hot Seven records in the late 1920s, his movie and radio appearances, even his late-career hit "Hello, Dolly!" that bumped the Beatles off the top of the charts at the height of their fame in 1964, all speak to his impact.

"Without Louis Armstrong, the history of jazz and American popular music does not go in the same direction," Riccardi said.

Ambassador Satch

And Louis is the quintessential American in another way.

In the 1950s, at the behest of the U.S. State Department, he became the country's goodwill ambassador — traveling to Africa, Europe and Asia to bring American culture to underdeveloped and Communist bloc countries.

"Ambassador Satch" had mixed feelings about it — after all, his country still treated him and others like him as second-class citizens, and Louis, contrary to popular belief, was a fierce civil rights advocate. He once told Eisenhower to "go to hell" when the president dragged his feet about desegregation. He explored some of those ironies in a 1962 album he did with Dave Brubeck, "The Real Ambassadors."

Yet there's no question that "Pops" was one of the greatest propaganda tools in Washington's arsenal.

"To a lot of international jazz fans, Louis Armstrong symbolizes America," said Riccardi, who has authored two Armstrong volumes ("Heart Full of Rhythm" and "What a Wonderful World") and is working on a third.

"He would show up in these countries where they couldn't understand a word of English, but once he started singing, it's great."

And for all his misgivings, when it came to boosting America, Armstrong didn't miss a beat.

"People in Japan, in Africa, all over Europe, when they think of America, they think of Louis Armstrong," Riccardi said. "And I think he really took that seriously. He would end his show with 'The Star Spangled Banner.' There's no more appropriate day for him to be born than July 4."

On exhibit

Those are just some of the reasons so many musicians, young and old, new and established, came out to Queens last Thursday, the week before Independence Day, to attend the ribbon-cutting, to celebrate — and to make a little noise.

"Just being able to continue that legacy is really important," said trumpeter Dave Adewumi, one of the young ones. He discovered Louis in 2009, when he was 14. Now he's here as a "teaching artist."

"I'm probably the first generation to discover [Armstrong] through the internet," he said.

Among the elder spokesmen was Teaneck's Jon Faddis, one of the most celebrated of modern trumpet players, who has recorded with everyone from Charles Mingus and George Benson to Tina Turner and Paul Simon (he was on the "Graceland" album).

"A lot of people still don't know who Louis Armstrong was, and what he did, and why he's important," Faddis said. "Here they can find out."

Location, location, location

Speaking of "here" — why here? Why put a museum in Corona, Queens, off the beaten path? In the middle of a residential neighborhood that is anything but glamorous?

That's a story, too.

When Louis married his fourth wife, Lucille, in October 1942, he had no real address. As one of the world's most in-demand musicians, he was on the road 300 nights a year, living out of trunks. For that matter, as a child in New Orleans, he'd had no permanent home either. He was raised partly by his grandmother, sister and mother in turn, partly by the Jewish family that employed him, partly in an orphanage.

So it was a big deal when Lucille phoned him, not long after their marriage. "She said, 'I've got something to tell you — I bought a house,' " Riccardi said.

The address was 34-56 107th Street, Corona, Queens. Right across from where the new Louis Armstrong Center is now. When the cab driver brought him there the first night (he got lost along the way) Louis kept insisting there had been some mistake.

"Lucille opens the front door, and he's outside arguing with the cab driver," Riccardi said. "He keeps insisting, 'Quit kidding me, and take me to the address I wrote down' and the cab driver kept saying 'This is the place.' He just could not believe she went out a bought a big house, garage, two floors.' "

That house, 20 years ago, became the Louis Armstrong Museum.

Visitors can get a glimpse of the modernistic all-blue kitchen where Louis cooked up his red beans and rice, his mirrored bathroom with the seashell sink, and the den where Louis had his tape equipment (he was a compulsive self-recorder). The Armstrong homestead, and the new Louis Armstrong Center, across the street, complement each other.

Good neighbor

It's a nice house. A large-ish house. But not the kind of spectacular house, in an exclusive neighborhood, that you might expect a celebrity to live in. That's Louis all over.

"He always referred to himself as a salary man," Riccardi said. "He said anybody who gets a weekly paycheck were his kind of people. This fact that the neighborhood had barbers, housepainters, waitresses, those were the people he wanted to be around."

The neighborhood — integrated of course — was a mix of Irish, Italian and African American in Louis' day. Now it's largely Latino. Faddis is hoping the new Armstrong Center will give it a boost.

"It's sort of a working class neighborhood, a lot of families," he said. "It's very special to have something like this."

It was special for Faddis too. On Thursday. he got to play Louis' actual trumpet. Or one of them.

"There are a lot of good notes in that instrument," he said.

Go...

Louis Armstrong House Museum and Louis Armstrong Center. 34-56 107th St, Queens. 718 478-8274. www.louisarmstronghouse.org

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Louis Armstrong museum opens, celebrating an American legend