Why a Harrowing 18th-Century Shipwreck Is a Parable for Our Times

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

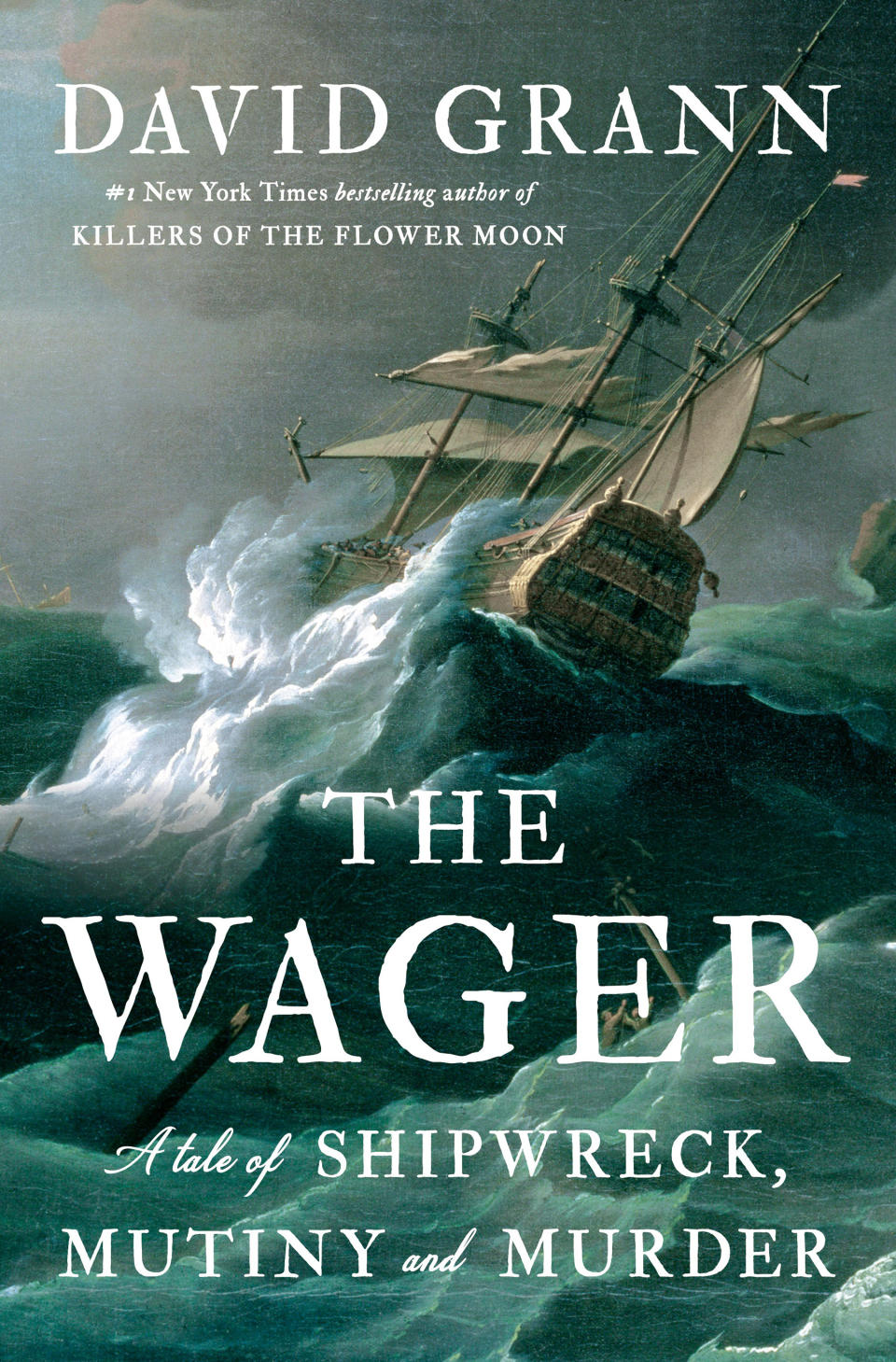

Writer David Grann is one of the premier nonfiction storytellers of our time. His bestseller The Lost City of Z transported readers into the Amazon on a quest for a mythical civilization (and became a 2016 movie starring Charlie Hunnam). He followed up in 2017 with The Killers of the Flower Moon, a blistering investigation into a series of unsolved murders of members of the Osage tribe in Oklahoma during the early 1900s (the film adaptation, directed by Martin Scorsese and starring Leonardo DiCaprio, premieres at Cannes this month). Grann’s masterful new book The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder is at once an adventure on the high seas, a horror story, and a courtroom drama — a little bit Rashomon meets Lord of the Flies. It’s the story of a doomed British naval vessel that sets out in 1740 to wage war against the Spanish and ends up wrecked on an island off the shores of Patagonia. The men are quickly divided. There’s mayhem, treachery, and death, imperialism and class struggle, lots of scurvy, and enough harrowing scenes to haunt any reader. When some of the survivors return to England years later with wildly different accounts of what happened, things get even weirder. There are competing accusations and narratives of mutiny and murder that lead to a court martial, where losing means death. Grann says the tragedy of the Wager is a “parable for our turbulent times. Just like in America today there was a battle over history and who gets to tell it and efforts by those in power to erase a sinful past.”

How did you find this story?

When I was looking for my next book, I was looking for something contemporaneous. The last place I expected to end up was in the 18th century. But I came across an old journal written by John Byron, who had been the 16-year-old midshipman on his majesty’s ship the Wager, when it set off on this doomed expedition. It was a very old book written in archaic, convoluted, faded English, but I kept pausing over these arresting descriptions about typhoons, scurvy, and then a shipwreck on an island that becomes a kind of Lord of the Flies, with warring factions, and there’s murder and even cannibalism. I realized that this document holds some clue to one of the more extraordinary sagas of survival and adventure I’d ever come across.

More from Rolling Stone

'This Is About Justice': OnlyFans Model Sued for Stabbing Boyfriend to Death

'I Am a Racist' Said Man Convicted Of Murdering BLM Protester

It’s incredible that anyone survived given the calamities and deprivations the crew faced.

Yeah, but I was looking for a deeper resonance. Why resuscitate and revive and spend years excavating something from the 18th century? But as I started to dive into archives and pull journals, I realized that as interesting as what had happened on the island was, what happened after several of the survivors made it back to England was even more incredible. They’d waged this war against every element and now, suddenly, they are summoned to face a court martial. And if they don’t tell a convincing tale, they could be hanged. And so, in hoping to save their lives, they release these various accounts trying to depict themselves as the heroes of the story. They all begin to wage a war on the truth.

Which feels very relevant now….

Right. I would come home and I’d flip on cable news or read the newspaper and there would be all these discussions about wars over the truth and disinformation and misinformation. Discussions of so-called alternative facts and fake news. And then I would go back to reading about the Wager. I’d be reading these documents about all these people shaping and manipulating their narratives. Then I discovered that there were even fake journals! And there was like an 18th-century version of allegations of so-called fake news.

That’s all too close to home.

Yes, because there’s a war over history right now. Like, what history books can we teach? There was a teacher who was afraid to teach Killers of the Flower Moon in her school in Oklahoma, and the books were just piling up.

That’s crazy.

Absolutely crazy. There were these wars of what books can be taught and what history could be reckoned with. And then I would go back to this story, and they’d be holding this war over history. There was a debate over who will get to tell the official history. And then of course, there were these efforts by those in power to cover up the past to essentially erase certain parts of it. And I thought, my God, this 18th-century story is like this weird parable of our own turbulent times. And that was why I decided to spend five years working on it.

It’s really a Rashomon-like story. When you’re dealing with competing narratives, as a journalist and a historian, how do you weigh the differing accounts?

At some level you can never completely resolve it. Joan Didion famously said, “We all tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Yet, in this case of the men of the Wager, they quite literally have to tell their stories in order to live. And if they don’t tell a good one, they’re going to get hanged. I had never seen such a case where you can see each individual shaping their story and burnishing certain facts and leaving out other facts. And so, I decided rather than try to be some omniscient being, the best way to handle it was just simply to show it.

There are still multiple conflicting accounts of the events.

I chose to tell the story from the perspective of three of the men, all of whom served on the Wager: Captain David Cheap; John Bulkeley, the gunner; and then John Byron, the midshipman. And thereby show how each one is shaping the facts. I leave it up to the reader to judge as best as they can. My feeling was that by doing that, you gain insight into how we all shape our stories, and how we all hope to emerge as the heroes of them — in order to live with what we’ve done or haven’t done.

The accounts vary widely in some places.

I’ll just give the most vivid example in the competing accounts: You have one senior officer say, “I was forced to proceed to extremities on the island.” And that’s all he says. There’s never been a greater bureaucratic phrase. And then you pick up John Byron’s version and he says, “The captain shot a guy in the head, and I had to cradle my friend bleeding out in front of me.” Right there you learn about each person, from what they leave out and what they choose to emphasize. But reading all of them together, I think it gets you pretty close to the truth.

What’s left out of history is in many ways some of the most tragic parts of the book.

Absolutely. One of the Wager’s castaways was named John Duck, who was a free black sailor at the time. And he is somebody who survives going around Cape Horn in a violent typhoon, he survives one of the worst scurvy outbreaks ever recorded. He survives the shipwreck and then survives one of the longest castaway voyages. And yet, unlike so many others, he cannot tell his story. He is kidnapped and sold into slavery. I could find no record of what had happened to him. The absence of John Duck’s story underscores how many chapters of history can never be told. I was as haunted in many ways by the gaps in the story — by the John Ducks. What his story drove home to me was that the most sinister crimes and worse racial injustices have been largely excised from the American consciousness.

The Wager is clearly about the cost of empire and yet most of these people on the ship are just trying to stay alive or make some money, and remain seemingly unaware that they are in the service of an imperialist nation.

They are completely unconscious. When you read their narratives in the journals, these people are either dreaming about heroism or rising in the ranks of the military, or coming back with riches or simply trying simply to survive to get back to their families. And many of them are victims of this system.

Some are just folks off the street who get kidnapped or press-ganged into service in the navy.

Many of these people didn’t even want to go on the damn voyage. They’re forced onto the ship. And I do think the narrative reveals how empires survive by having so many citizens, consciously or not, who are complicit. So many of these people are complicit in a system that is also victimizing them.

I kept thinking about the Iraq war and America’s own imperial ambitions and folly.

I thought of Vietnam and the Gulf of Tonkin. The roots of the war are absurd. It’s called the War of Jenkins’ Ear, after Spanish forces allegedly cut off this British sailor’s ear. This story is kind of touted by imperialists as a pretext war. They were really just looking to expand the British empire. You realize how much history informs the present. We’re standing on history; it’s always there. In many ways this story is an illustration about how empires preserve power, not only by the stories they tell, but also the stories they leave out.

You’ve written about explorers who get lost in the Amazon and someone trying to cross-country ski across Antarctica. Why are you drawn to extreme stories?

Those circumstances are like these little laboratories that test the human condition. They end up revealing something, the kind of secret nature, the hidden nature of us, the good and the bad. And you can really see it play out. So I think they’re revelatory sorts of tales. Like in the Wager, you see these selfless acts, and then the same person, moments later, will commit a shocking act of brutality.

It all goes south very fast for the men of the Wager.

They descend into a Hobbesian state of nature. They start off with the imperial notion that Western civilization is somehow superior, yet they descend into warring factions and there are mutinies and murders, and a few even succumb to cannibalism. Which is probably why the British Empire wants the story to go away. They don’t want to admit that British officers didn’t behave like gentlemen, they behave like brutes.

Shifting gears, the Killers of the Flower Moon movie is set to premiere soon. What can you tell us about that?

It’s premiering at Cannes and out in the United States in October. I’m not a movie person, I’m a nerdy writer. But I feel very fortunate and blessed working with Martin Scorsese and Leonardo DiCaprio and that whole production team has been pretty remarkable. You hope with these projects that you’re going to find people who have the same fierce commitment to the story as you do, which isn’t always easy. This is an important story to get right, because in the case of Killers of the Flower Moon, this is about an outrageous racial injustice that had been papered over in much of our collective consciousness.

Did the filmmakers work closely with the Osage nation?

That is the most important question to me. When people say, “What has the experience been like?” — like, I wrote a book, I did my best with that. And so, for me, the most important thing is that the people in the film work closely with the Osage nation. And, and to the best of my knowledge, the Osage were deeply involved in the production and the shaping of the story at every level. And the good news is after the experience of filming Killers of the Flower Moon, Scorsese and DiCaprio asked if we can team up again for a film about the Wager. I was like, “Oh, yeah, that sounds good to me!” [Ed. note: DiCaprio’s rep would not confirm if this was in the works.]

OK, so, you’ve written about the Amazon, the shipwreck of the Wager, and a deadly trek across Antarctica on skis. How would David Grann do in any of these experiences?

I’m like a little nerdy guy. I’m basically half-blind, bald, out of shape — at this point, sadly, an older gentleman. The idea for me to go exploring is the most preposterous thing in the world.

Best of Rolling Stone