Who has the leverage? As MLB, players negotiate baseball's return, experts assess pay cut question

On Tuesday afternoon, Major League Baseball will present the players association with a proposal to start the 2020 season. In addition to addressing schedule and travel logistics amid the coronavirus crisis, the new plan asks players to agree to a 50/50 share of revenue for this season only. Without in-stadium revenue, at least at first, this likely amounts to a serious pay cut for the players — one that the union has publicly said it will not abide.

The MLBPA will cite a March 26 agreement to prorate salaries for the season based on the number of regular season games. The league now says that without fans in stadiums, doing so would amount to an economic loss for owners. And in turn, the union will almost certainly demand that the league open its books if the owners plead poverty.

Despite a mutual motivation to salvage the sport and a public expectation that the pandemic will inspire both parties to set aside their differences, the negotiation at the bargaining table — at least with respect to economics — is going to come down to legal might and leverage. So we talked to two labor law experts to understand how this might play out, including whether the union could compel financial transparency by the league.

[Get the latest updates on MLB’s progress toward reopening]

David Rosen and Arnee Cohen have each been practicing labor law for over 40 years. Rosen represents management clients and Cohen represents labor unions. We provided them with a copy of the March 26 agreement obtained by Yahoo Sports and asked them for their perspectives on the upcoming collision between MLB and the players. We grouped their answers, edited lightly for length and clarity, by topic but they spoke in separate conversations.

These conversations do not deal with the incredible health implications of reopening baseball — either for the public at large or the players and staff who would be assuming the associated risks. We did not talk about what would happen if a player tested positive or whether baseball should be a priority during a pandemic. Neither lawyer has any direct dealings with Major League Baseball nor any specific insight into baseball’s negotiations.

We were interested, instead, in their expert understanding of the legal context for the forthcoming negotiations.

Based on that March agreement, how can the league ask the players to take a further pay cut or amend the payment structure? Didn't both sides already agree that players will be paid their prorated salaries? Regardless of the financial impact of not having fans, what is the legal standing for the league to come back and say it actually wants something different now?

David Rosen: I think the answer turns upon how they wrote that agreement. Everything in that agreement, including what payments players would receive, is predicated on the commissioner’s decision to resume the season. There's nothing in the agreement that requires him to do so. And in fact, there are so many conditions that are available to prevent the commissioner from doing so that the owners, in my mind, have all of the leverage here. There's no violation of the agreement, unless you resume the season and don’t honor the terms of the agreement. If there is no season, there’s no money that’s due.

So now we have a situation where the owners could, whether or not they're bluffing I really don't know, if they could choose to say, “We're not going to reopen.” And of course the commissioner is controlled by the owners. They can simply say, the economics, being what it is, we can't get enough gate receipts, our costs are going to exceed what our revenue is going to be, and it makes no sense from a financial standpoint to play games now.

Arnee Cohen: It’s already addressed. They can come back and ask for it, but that doesn’t mean the players association has to agree to it.

I think the union would have a very strong argument that “you signed in March that you have to pay our salaries, and we thought about all the contingencies, and everything that was contemplated is part of the agreement and there's nothing else, you have to pay our salaries,” according to the terms of that agreement.

If the league insists it’s not economically feasible to play without fans, would that constitute pleading poverty? Could the union force them to prove it by opening up the books?

Rosen: The term, “where economically feasible,” is so vague it literally could mean anything. The commissioner retains the discretion to determine whether or not it is “economically feasible” to play the games at substitute neutral sites, and I believe that based on how that paragraph is worded, his discretion is virtually unreviewable. The owners would NOT be saying they cannot “afford” to play the games there; they’d only be saying that without a revenue stream from the fans attending the games, it is not “economically feasible” to do so. I don’t believe that position, in and of itself, would require the owners to “open their books.”

Normally what you do is you file an unfair labor practice charge with the National Labor Relations Board — if you're claiming that the owners are bargaining in bad faith because they are seeking concessions and they're not allowing the union to inspect their finances. Problem is that those particular charges can take months and months to resolve. By the time that ever gets any resolution the season's over.

The players wouldn’t get remedial action soon enough to salvage the season. Plus, that particular law is a little bit toothless. There are no financial penalties. So the only thing that the labor board can do is issue a cease and desist order and tell the owners to open their books and go back to the bargaining table, and that's after an investigation that may take months. So I don’t see that that’s a lot of leverage.

Cohen: They could, yes. But historically teams have lost money. They don’t necessarily do it to make money, the owners. If you have a contract, the contract stands — whether you can pay or not.

The opening of the books come in normally when you’re negotiating a contract, but the union is taking the position that they have a contract. They can ask them to open their books, but they really don’t need to because they can just say, “We have a contract.”

Let’s say the conversation does move forward with the revenue sharing plan at the center of efforts to resume play. How could a skeptical players association determine if it was actually getting its fair share of the money?

Rosen: Well, if there is a claim that the owners are violating the terms of the revenue sharing agreement — should they reach one — then I think the remedy would be to file some kind of an arbitration demand. I suspect that an arbitrator, upon the service of the subpoena, would require the owners to share information that might support their claims of a breach of contract.

And of course it is predicated on projected revenue. So the only time it's going to come up now, if somebody claims they didn’t share all the revenue they were supposed to, would be at the end of the performance of the agreement.

Cohen: If they were going to renegotiate this contract and it was based on revenue sharing, they would be able to look at past years’ revenue. That would be something that would be relevant for them to look at. I don’t know if past years would necessarily tell them that much because this situation this year is so different, but yes they would have the right to look at that.

They would file an unfair labor practice charge with the National Labor Relations Board. It wouldn't happen that quickly. I mean there are mechanisms for going to court to enforce the rights of the parties that are violated, but it's usually a pretty slow process. So I don’t know that that would realistically help things, going to the National Labor Relations Board.

I mean this would be a high-profile case so probably the NLRB would go to court on behalf of the union to get them to turn over the information. But you never know. And they want to resolve this pretty quickly. The National Labor Relations Board is not really the perfect avenue for getting things done quickly.

If you want revenue sharing, the union wouldn’t blindly accept it or even consider it. They couldn’t force them to accept it either, assuming that the March agreement is a binding agreement.

If the fight comes down to whether or not the March agreement is binding — and the owners are obligated to pay the players the previously agreed-upon prorated salaries — who would win that fight in front of an arbitrator?

Cohen: Normally the union would win that fight. But under these circumstances, you never can tell. An arbitrator might find that it was such a unique circumstance, through the whole country and the whole world, that they might not rule in favor of the union.

I represent a group of nurses at a hospital and the hospital decided that they didn’t want to agree to let the nurses work in a separate hospital, have a second job, and that’s something that the contract said they specifically could do.

And we went to the public sector equivalent of the National Labor Relations Board. And they ruled against us. They said that under the circumstances, if the hospital decided they didn't want the nurses to have a second job, they could do that.

But the general rule is, you go by the four corners of the contract. Whatever contracts say, you don't look to the outside circumstances, but you know this is such a unique situation that who knows.

But if they don’t play, the owners will blame it on the players in public.

Rosen: Everything is optics and everything is perception. And here you have, you know, almost 15 percent unemployment in this country, and only going higher. People are struggling to eat and to pay their rent, and they know these players, even when they're not getting paid, are extremely wealthy. At least most of them, except for the very youngest players who are playing under minimum contracts — and even those are higher than anything that most people may see in their entire lifetimes.

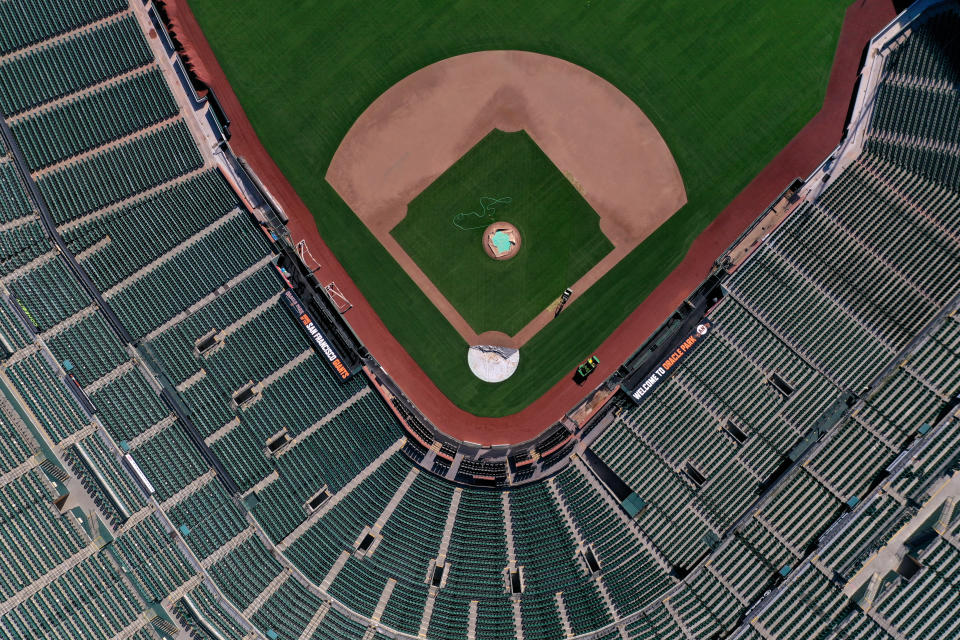

And I think that people would say, just common sense, if no one's coming to the games and they're not paying for tickets, and they're not buying hot dogs and refreshments, and the stands are empty, then it's the height of audacity for the players not to share more in the losses and to play for a sports-starved populace. Yeah, you know, so I don't think that there's going to be a whole lot of sympathy from the public. And I think that's another leverage point.

I would say, if I were the union, in response to that, “Well look, we don't benefit extra in the good years. We always make our salaries. We don't make more if the valuation of the franchise goes up. When MLB signs new TV deals we don't see a cut of that.” So why should they take less than their salaries this year?

Rosen: I think that they can fight to the last drop of their own blood to prove a point that they do not have to give any further concessions. And they don't! That it’s a matter of principle, I agree. And we’ll still have no baseball. I don’t see how you win in the court of public opinion, and I don’t see how you win in time to save the season. I think that right now, the balance favors the owners in terms of their ability to get these further extractions, if the players want to play the season.

So who has the leverage?

Cohen: I would say that the players do, because the owners don't want to jeopardize — they're losing out on the fans coming to the stadiums, and they don't want to lose out, on top of that, on the television revenue. So I think the players do.

But ultimately, can the owners just hold the season hostage and demand the players take a pay cut?

Rosen: They don’t have to be reasonable about this. The players association agreed to a contract that gave most of the rights to play to the owners and the commissioner. And they can choose not to. [The owners] can simply say, “Health conditions being what they are, we still have a national emergency, it's not safe. And in the interest of protecting the players from getting sick, and every other personnel that are related to ballparks, you're not going to play the season.” They can do that. That's the way that this looks. That's the way it reads.

More from Yahoo Sports: