What's behind the epidemic of concertgoers throwing stuff at artists?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

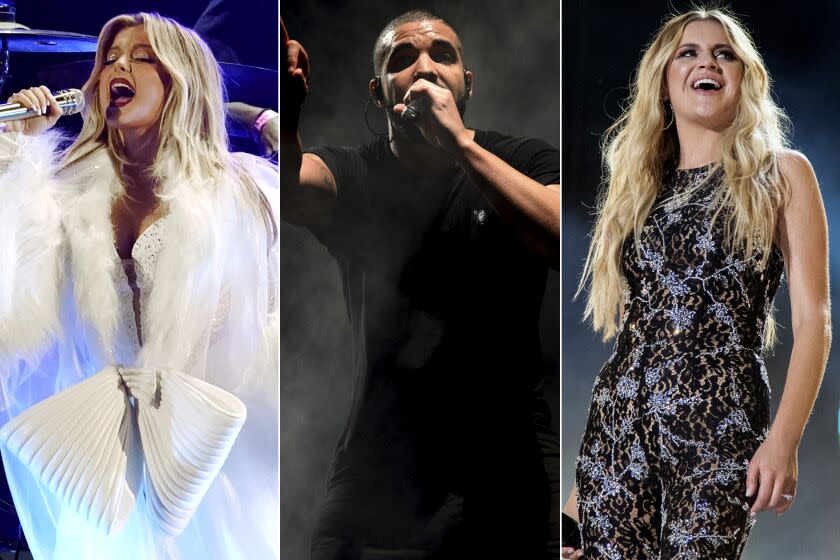

On Wednesday, the opening night of Drake’s new tour, the superstar rapper was midway through a tender version of Ginuwine’s “So Anxious” when a cellphone flew out of the Chicago arena crowd and smacked him in the wrist. Drake kept on singing, uninjured if a bit confused why someone would throw a valuable — and dangerous, when airborne — object at him midshow.

Who knows if the fan had intended to hurt him, or if they hoped Drake would take a selfie onstage with it (and toss it back?). But Drake’s pelting is just the latest in a string of incidents where fans have chucked objects ranging from phones to jewelry to cremated ashes at performers.

Strikingly, many of these artists — Bebe Rexha, Kelsea Ballerini and Ava Max, among them — are female singers, with fan bases that lean more toward impassioned singalongs than aggravated assault. Still, no one seems immune: Pink, Kid Cudi and Steve Lacy have all been on the receiving end of hurled objects at recent shows. On Saturday, in Vienna, Harry Styles joined their ranks when a fan threw something, hitting him in the eye and causing him to double over and briefly walk offstage.

“Fans throwing projectiles at artists is as old as rock ’n' roll, but there’s still no excuse for it,” said Paul Wertheimer, a concert security expert and founder of the consulting firm Crowd Management Strategies. “The line between the stage and audience, and the sense of decorum around it, has really faded.”

The incidents range in severity, from Drake’s errant whack to Lacy smashing an airborne phone in New Orleans last year, to much more violent and criminal assaults. Perhaps the weirdest incident came when Pink found a small bag of powder onstage at a London show last month. "This is your mom?" Pink asked the fan as she picked up the bag, reportedly containing cremated ashes. "I don't know how I feel about this."

Read more: Ashes to cheeses, remains to brie: Pink keeps getting weird gifts onstage from fans

Last month, Nicolas Malvagna, 27, was arraigned in New York on misdemeanor charges of assault and harassment after he allegedly threw a phone at Rexha, 33, hitting her near her eye. Rexha collapsed onstage while crew rushed around her. According to the criminal complaint, Malvagna reportedly said, “I was trying to see if I could hit her with the phone at the end of the show because it would be funny.”

Read more: Eye protection, but make it chic: Bebe Rexha's shades shield her face after phone fiasco

A day later, a man rushed the stage and slapped pop singer Ava Max during a show at the Fonda Theatre in Los Angeles. “He slapped me so hard that he scratched the inside of my eye. He’s never coming to a show again,” Max tweeted the next day.

While it’s not entirely clear what led to Max’s apparent assault, Wertheimer says it should be seen as part of a pattern that includes such grim episodes as Pantera guitarist Dimebag Darrell’s onstage murder in 2004 and the after-show killing of singer Christina Grimmie in 2016. “The industry has learned nothing since then,” Wertheimer said. “That could have set something horrible in action that could have cost Ava Max her life.”

Meanwhile, 29-year-old country singer Kelsea Ballerini paused her show in Idaho after a fan hit her in the eye with a bracelet.

“Can we just talk about what happened?” she asked the crowd. “All I care about is keeping everyone safe. If you ever don’t feel safe, please let someone around you know. If anyone’s pushing too much or you just have that gut feeling, just always flag it. … Don’t throw things, you know?”

Read more: Kelsea Ballerini hit in the face during concert by fan-thrown object

This month, rapper Sexxy Red ended two shows after fans threw objects at her, leading her collaborator NLE Choppa to chastise them on Twitter: “Y'all need to stop doing people like that and treating people like that….Y’all need to stop doing that girl like that."

Even superstars like Adele have had to get out in front of such behavior. “Have you noticed how people are like, forgetting show etiquette at the moment?” she told a crowd during her Las Vegas residency this week. “People just throwing s— onstage, have you seen them? I f— dare you. Dare you to throw something at me and I’ll f— kill you.”

Wertheimer said that while he wasn’t convinced this is a wholly new trend — “This has been happening at rock shows since the 1950s” — it is consonant with a general feral atmosphere at shows and festivals today.

“We knew at the beginning of this concert season that crowds were more rambunctious,” he said. “Young people want to get crazy. They lost a huge part of their lives during the pandemic.”

Carla Penna is a psychoanalyst and crowd researcher in Rio de Janeiro, and author of “From Crowd Psychology to Dynamics of Large Groups.“ She said that social media and fan culture have shifted the borders between fan and artist, and that influences the sense of physical space at shows.

While throwing a cellphone at an artist seems irrational, the object could carry a psychological meaning for fans.

“With the support of unbounded social media, the real or fantasized distance between the fan and the artist diminished,” Penna said. “Thus, in a show, the audience might feel entitled to join the artist in person on the stage or join the artist in a symbolic way by throwing objects that represent or symbolize themselves.”

Penna agreed that “misogyny is a possibility” when it comes to the recent spate of attacks, saying, “Female artists have always been targeted as victims of criticism or violence.” But she also cited changing consumer expectations and post-pandemic rage as reasons why the border between fan and artist is deteriorating.

“After 2½ years of lockdown and social distance, people changed their behavior, and many still feel uneasy in crowded or confined spaces. Domestic violence, self-harm, intolerance to noise, feelings of disrespect and invasive behavior increased,” Penna said.

Simultaneously, “Audiences became more demanding and assured of their rights as consumers,” she said, citing a recent instance at the Rock in Rio festival where fans threw bottles of urine at metal bands they didn’t care for. “Crowds are demanding. We should never ignore for good and for worse their power."

There may not be much a venue or an artist's crew can do about a fan who really wants to throw a phone — or a relative's remains — from the distance of a pit seat. (Rexha has since taken to wearing protective goggles onstage.)

Still, artists should be vocal about demanding venue safety and crowd control, Wertheimer said. After the mass shooting at Las Vegas' Route 91 Harvest festival, the deadly crowd crush at Houston's Astroworld concert and last month's fatal shootings at Beyond Wonderland in Washington state, any chaos in the crowd is cause for fear.

“Things have gotten way worse,” Wertheimer said. “You can be at a venue run by the world’s biggest promoter, or a festival headlined by the biggest artists in the world, and you just don’t know which shows are safe and which aren’t anymore.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.