Were Wings really the band The Beatles could have been?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

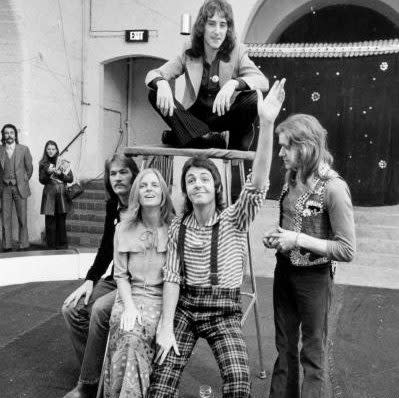

There can be fewer more savage takedowns of a songwriter than journalist Philip Norman’s satirical poem about Paul McCartney in 1977. The former Beatle was enjoying global success with his band Wings – the group he’d formed with his American wife Linda after the Fab Four imploded in 1970 – when the rhyme was published in the Sunday Times Magazine. It ended, “Oh, deified scouse with unmusical spouse / For the clichés and cloy you unload / To an anodyne tune may they bury you soon / In the middlemost midst of the road.”

Norman’s poem, which he admitted in his 2016 biography of McCartney seems “horrifically tasteless” today, played into the general narrative that Wings were a bit naff. The idea that, separated from his Beatles’ songwriting partner John Lennon, McCartney was a musical lightweight who was prone to releasing sentimental and self-satisfied music. That narrative about Wings persisted.

When Steve Coogan’s fictional character Alan Partridge chatted about music with hip young hotel worker Ben in 1997 sitcom I’m Alan Partridge, the washed-up talk show host referred to Wings as “the band the Beatles could have been”. It was comedy, yes, but it nailed the perception that Wings were the preserve of middle-aged men with dubious taste; men who may possess a state of the art Bang & Olufsen stereo, as Partridge did, but don’t know what to play on it.

But such perceptions are harsh. While it would take a brave person to argue that Wings were a better band than the Beatles, they still produced some fantastic music. Further, they were wildly successful – a fact often overlooked by the naysayers.

The chief criticism levelled at McCartney was that Wings churned out mawkish and winsome love songs. It’s an issue he addresses in his mammoth new book about his songs, extracts of which have been released. “There were accusations in the mid-Seventies – including one from John – that I was just writing “silly love songs”. I suppose the idea was that I should be a bit tougher, a bit more worldly,” McCartney says, before adding ‘So what?’ “A lot of people who are cynical about love haven’t been lucky enough to feel it. It’s easier to get critical approval if you rail against things and swear a lot, because it makes you seem stronger.”

Railing against things and swearing a lot was something that post-Beatles Lennon was particularly good at. Which is why McCartney played up to the perception of himself and wrote the track Silly Love Songs in 1976. The opening lines were a sharp retort to his critics: “You’d think that people would have had enough of silly love songs / I look around me and I see it isn’t so.”

Crucially, it’s also a finely structured song. Silly Love Songs has a bouncy bassline, an indelible melody and fabulous horns provided by musicians including Howie Casey, who’d performed on the Hamburg club circuit alongside the Beatles in 1960 and played saxophone on T. Rex’s 20th Century Boy. The song may not have gravitas but McCartney has always known that pop music needn’t be heavy. The same could be said for Maybe I’m Amazed and Coming Up, songs that were recorded solo by McCartney but formed part of Wings’ live sets.

Wings could do foreboding too. Their theme to 1973 Bond film Live and Let Die is a multi-part belter that was nominated for an Oscar (it lost to Barbra Streisand’s The Way We Were) and was covered almost two decades later by rockers Guns N’ Roses, whose version was nominated for a Grammy. Wings could also do weird. Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey (a Paul and Linda effort that was included on Wings hits compilation) is a crackers medley. It sounds like the wayward young cousin of McCartney’s more stately medley on Abbey Road. After all, Paul was still Paul.

The band were always bigger in the US than they were here, perhaps because American audiences were less cynical and more accepting of naked sentimentality in their music. While Wings had just one chart-topping single in the UK (1977’s Mull of Kintyre, the song that sparked Norman’s ire), they had six across the Atlantic. Almost half the dates on the band’s huge Wings Over The World tour of 1975 and 1976 were in the US, and these shows accounted for well over half the ticket sales.

One of the reasons the British press were so down on Wings was Linda. Starting a band that wasn’t the Beatles was bad enough, but replacing Lennon with your wife was too much to bear. An isolated audio file of Linda singing backing vocals to Hey Jude at a McCartney concert (presumably released online by a cruel sound engineer) does lend credence to Norman’s “unmusical spouse” barb. But that misses the point. As McCartney says in The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present, Wings was his and Linda’s “escape” from their respective gilded cages (his being the Beatles, hers being New York society). Wings were always meant to be a little homegrown and DIY. They were deliberately un-slick.

McCartney didn’t need the money or fame. He just craved reinvention. As he says in his book, “I wanted to flee from what the Beatles had become.” He needn’t have worried. With Wings he succeeded on almost every level.

The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present (Allen Lane, £75) is published on November 2