‘Like copyrighting Moses’: hands off our water spirit, say First Nations

People living on the shores of Okanagan Lake have long said that dark, curling waves signal the presence of Ogopogo, a monstrous serpent lurking beneath the surface.

A handful claim to have seen the long green body and horse-like head of Canada’s own Loch Ness monster. They tell stories of a creature that once nearly killed a settler when it dragged his horse into the depths. And every few years, new video footage renews excitement that Ogopogo has been found.

Indigenous residents tell a very different story: one of a sacred water spirit whose identity has been warped by outsiders.

Now, a move to return ownership of the Ogopogo legend to a First Nation has renewed discussions over the appropriation of traditions – and the challenges Indigenous nations face in reclaiming their culture.

Okanagan Lake is a 84-mile sliver of water in British Columbia, famed as a summer vacation spot, and as home to the monster.

But Ogopogo recently became the focus of controversy when the city of Vernon granted a children’s author permission to use the monster’s name for his upcoming book.

The city had held the copyright since 1956 when it was donated by an enterprising local reporter, but that fact was not widely known, and the revelation that local officials had control over the name came as a shock to nearby First Nations.

“We equated it to someone taking ownership over the Bible and suddenly copyrighting the name Moses,” said Chief Byron Louis of the Okanagan Indian Band, one of the seven communities of the Syilx Nation. “The idea that someone can take ownership of your teachings and your religious beliefs is absolutely unacceptable.”

After Louis and others voiced concerns, the council voted in late March to transfer the copyright to the Syilx Okanagan Nation.

“It’s much more than just simply a gesture,” said Louis. “It’s the city saying ‘This is not ours. This is yours.”

The name Ogopogo comes from an English music-hall song, but the creature itself is based on a Syilx water spirit named n ̓x̌ax̌aitkʷ (pronounced n-ha-ha-it-ku)

Although the Ogopogo is depicted as a fearsome reptile, the Syilx say the spirit, which can take the form of a dark serpent with antlers, spends most of its time in its true form: the water itself.

The Syilx would sing to the spirit, gifting it sage, tobacco and salmon. But early settlers mistook the gifts as sacrifices to a monster.

“The gifts were an acknowledgment that the blessings and abundance we have come because of our water,” said Coralee Miller, from the Sncewips Heritage Museum.

Over the years, purported sightings of the creature became increasingly common but the meaning of the n ̓x̌ax̌aitkʷ gradually faded.

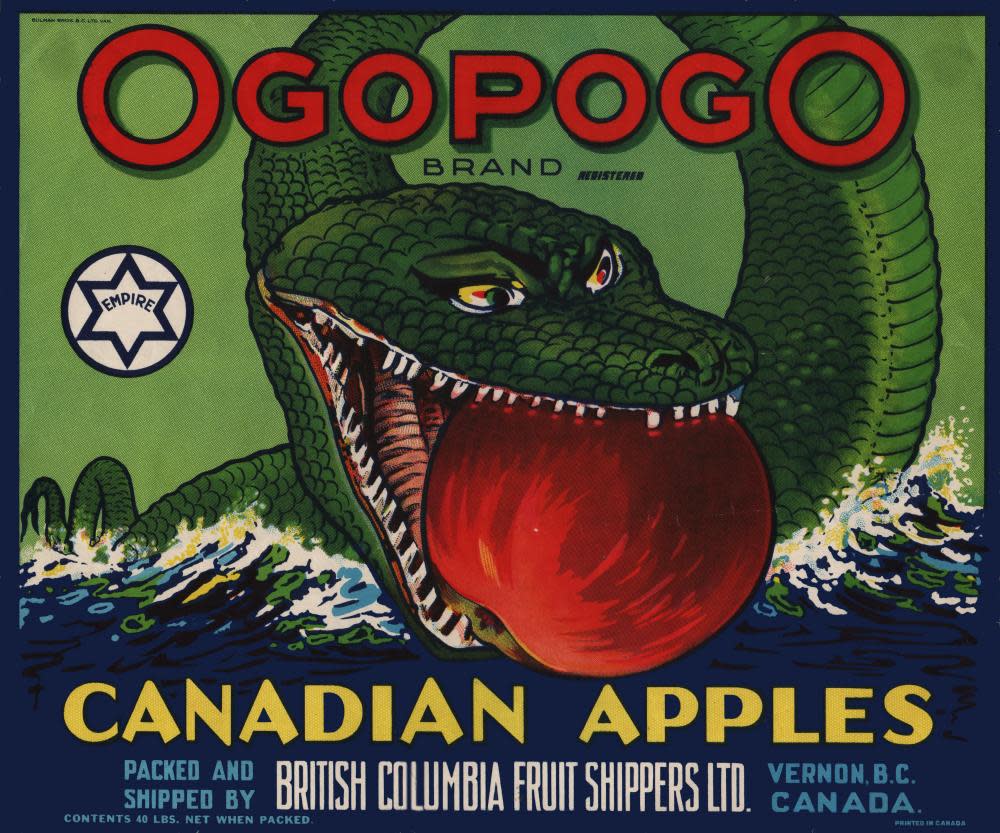

“What is supposed to be a metaphor for taking care of the water and the people that are connected to it gets lost,” said Miller. “Now, this sacred water spirit has become a fishing derby mascot that sells apples, beef jerky and irrigation lines.”

The controversy also speaks to broader questions across Canada over the appropriation of Indigenous storytelling: Ogopogo is far from the first cryptid to be transformed by non-Indigenous retelling.

The Ojibwe wiindigoo was traditionally described as a giant, foul-smelling creature with an insatiable appetite. Now known as the wendigo, it is depicted as a wiry creature with antlers, used to sell brands of gin and tea.

The Sasquatch – derived from the Halkomelem word ‘Sasq’ets’– has gone from being a cautionary tale for children to a lumbering forest ape named Bigfoot. Sightings in the wild persist, but nowadays it’s far more likely to be seen hawking snowshoes, beer, camper vans or beef jerky.

“It’s outsiders choosing which aspect of our culture to elevate, not us. And often, they choose just the cheesiest interpretations of our cultures – and this becomes what we’re about,” said Robert Jago, a Kwantlen First Nation citizen and prominent writer on Indigenous issues. “I don’t think you can find [many] children in a Salish nation that know the name of their god. But 100% know the name Bigfoot.”

The practice speaks to a broader trivialization of Indigenous culture, in which headdresses and sage that are sold as novelties despite pleas from Indigenous people, Jago said.

“People treat these requests like an esoteric curiosity. They’re confused, they wonder what this could possibly be about,” said Jago.

Ogopogo’s immense popularity as a marketing tool misses out on the important meanings behind the story of n’x̌ax̌aitkʷ, said Miller.

After a C$1m bounty was placed on the Ogopogo in the 1980s, Greenpeace declared the serpent an endangered species.

But while the group focused on the beast itself, they did not take action over pollution of the lake, she said.

“We see diapers and beer cans being tossed into our lake,” said Miller. “And [Greenpeace] wanted to protect Ogopogo,” said Miller. “They were so close. They almost understood what needed to be protected.”