Warner Bros. at 100: How a Band of Brothers Built a Cornerstone of Hollywood

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

David Zaslav went office-furniture shopping when he moved into the executive building on the Warner Bros. lot last year. The new CEO of Warner Bros. Discovery had Jack L. Warner’s large dark-wood desk pulled out of storage for his use. He also found a leather legal pad holder once clutched by another of his predecessors at the storied studio: Steven J. Ross.

Zaslav wanted these totems in his sunken workspace overlooking Olive Avenue in Burbank to show the formidable legacy, in business and in popular culture, he has inherited.

More from Variety

Warner Bros. at 100: Characters of Steel Propel DC Into Future

Warner Bros. at 100: Studio Was Early Entrant Into TV Production

Warner Bros. at 100: Big Bets on Film Talent are Part of WB Pictures' DNA

“I wanted them to remind me that we need to show as much courage now in leading this business as the Warner brothers did in launching it one hundred years ago,” Zaslav says. As the studio marks the centennial of its incorporation as Warner Bros. Pictures Inc. (the official date is April 4, 1923), the company has never been more focused on using the wealth of intellectual property assets, the production expertise and the global distribution muscle built up over the past 100 years to power its second century. The vast Warner Bros. movie and TV library is the foundation of WB Discovery’s empire-building ambition to transition from traditional cable to direct-to-consumer streaming.

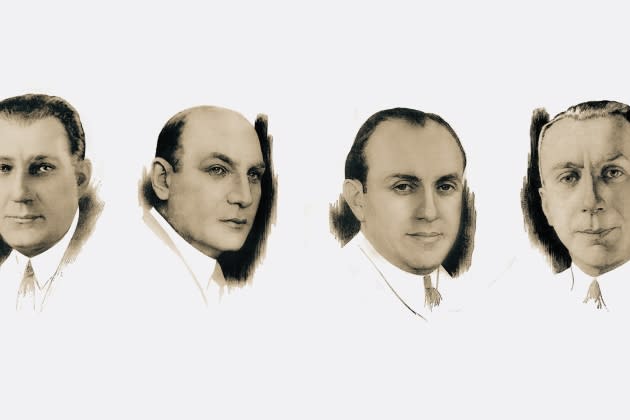

But the 12,500 movies and 2,400 TV programs in the vault aren’t the only elements of the past guiding Warner Bros.’ future. From its earliest days, the studio built by four brothers (Harry, Sam, Albert and Jack) who ran nickelodeons and silent movie theaters in Pennsylvania and Ohio has had a distinct profile to its storytelling and an ethos on how to wield its influence. Where MGM offered lavish escapism, flowing gowns and tuxedos, Warner Bros. served up from-the-headlines realism, potboilers and melodramas that often touched on social ills and other contemporary themes. Warner Bros. pioneered the gangster movie (“Little Caesar,” “The Public Enemy”) and turned Bette Davis loose on-screen in dozens of 1930s films that helped establish the archetype of young American women as tough, smart and sassy — nobody’s fools.

“MGM was the glamour studio. Warner Bros. was a grittier studio,” says film critic and historian Leonard Maltin. “It showed in the kinds of stars they hired and nurtured. They went for unlikely people who didn’t fit conventional definitions of beauty or handsomeness: Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney, Bette Davis, Humphrey Bogart. The brisk pace and torn- from-the-headlines stories — none of that was accidental or coincidental. That was Warner Bros.’ stock in trade.”

WARNER BROS. AT 100: MORE COVERAGE

Warner Bros. Pictures: Big Bets on Talent are Part of Studio’s DNA

Warner Bros. Television: Studio was Early Entrant into Series Production

DC Comics: Characters of Steel Propel Studio into Future

Harry, the oldest, functioned as CEO in his role as president of Warner Bros. Pictures. Sam was essentially chief technology officer and chief operating officer. Albert oversaw all distribution operations, while Jack, who was nearly 11 years younger than Harry, called the shots as the showman with a vision for production and creative talent.

The brothers had a lot of experience by the time they raised the iconic WB shield logo on the West Coast as Warner Bros. Pictures. The foursome had been active in the “amusements” business and distribution of silent features and shorts since the late 1900s. They moved into producing their own movies soon after. The efforts of the brothers Warner began to gain traction — and notice in the pages of Variety — around 1917 and ’18 with silents such as “Are Passions Inherited?” and “My Four Years in Germany.”

Warner Bros. was a forerunner of today’s modern media conglomerates. Led by Harry and Sam, it very strategically pursued growth through acquisitions. The brothers bought Vitagraph Studios in 1925 for its sound technology assets — and wound up revolutionizing the film business with the release of the first mainstream “talking picture,” 1927’s “The Jazz Singer” starring Al Jolson. (Fun fact: Early on, Variety referred to sound films as “talkers” rather than “talkies.”)

In 1928, WB bought Stanley Corp. of America theaters and First National Pictures, which came with the 85-acre lot in Burbank that the studio still calls home. In the 1930s, Harry picked up a slew of sheet music publishing companies, then launched the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoon production imprints to promote the songs.

“The family had two extraordinary visionaries in Sam and Harry,” says Cass Warner, who is Harry’s granddaughter. “They saw the potential of putting movies together with music and sound.”

Sam’s story could be a movie unto itself. Known as a perfectionist, he would pull off miracles that kept the studio afloat. In 1925, his interest in burgeoning communications technology led Warner Bros. to become the first Hollywood studio to invest in broadcasting, with the launch of Los Angeles radio station KFWB (aka Keep Fighting, Warner Bros.). From there, he threw himself into readying the company’s Vitaphone synchronized sound system to impress moviegoers at the Oct. 6, 1927, premiere of “The Jazz Singer” at the flagship Warner Bros. Theater in New York. The day before the studio’s greatest industry triumph, Sam would die at a Los Angeles hospital of a sinus infection that led to pneumonia. When Harry Warner rushed from the East Coast to be with his brother, he changed to a special private train in Albuquerque to speed up his arrival in Los Angeles, but he still was four hours too late, as Variety reported in its Oct. 12, 1927, obituary for Sam.

In the wake of “The Jazz Singer” — and its famous promise, “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet” — Warner Bros.’ competitors had no choice but to embrace sound and race to catch up. The big bet on innovation energized the studio that had previously banked on a German shepherd named Rin Tin Tin as its biggest box office draw. Warner Bros. has not only been a titan of Hollywood ever since, it’s been a force in exporting American culture and ideals around the globe.

“They were producing over 100 movies a year in the 1930s,” says Zaslav. “Back then, if you lived on a farm or in a small town, movies were how you saw the world, how you learned what New York looked like, how people would dress to go on a date. The motion picture business sharpened our view about what it means to be an American.”

Harry Warner in particular was deeply patriotic, idealistic and observant of his Jewish faith. At his direction, the studio produced issue-oriented movies such as “The Black Legion,” which took on the Ku Klux Klan, and historical dramas such as 1937’s “The Life of Emile Zola,” which bagged WB’s first best picture Oscar. “Confessions of a Nazi Spy” in 1939 was one of Hollywood’s first efforts to address the rising tide of fascism in Germany. Around that time, Warner Bros. was the first major Hollywood player to stop doing business, on principle, with Hitler’s Germany.

The studio’s success took the Warner family to unimaginable heights and, inevitably, emotional lows, most notably the notorious sale of much of the studio’s library that Jack orchestrated in 1956. He encouraged Harry and Albert to sell their shares — and then secretly bought them back and stayed atop the studio until it was sold again in 1967 to Seven Arts Prods. Two years later, Kinney Corp., a conglomerate that got its start operating parking lots and funeral homes, acquired Warner Bros.-Seven Arts. Kinney chief Steven J. Ross took the studio reins, setting the company on the path to becoming Time Warner, the largest media company in the world, after its merger with Time Inc., in 1990.

For Cass Warner, who has documented the family history in books and the 2007 documentary “The Brothers Warner,” seeing the shield reach the century mark feels “very validating” for the work put in by her grandfather and granduncles. Harry and Albert were still estranged from Jack at the time of their deaths (in 1958 and 1967, respectively). Jack Warner died at 86 in 1978.

Cass Warner has high praise for Zaslav and his team, who connected with her early on after closing the deal with AT&T to acquire WarnerMedia in April 2022.

“They would be so happy to see that their dream was still alive and well and expanding,” Warner says. “My grandfather would be thrilled to see all the new ways that people can communicate with each other. The company’s original motto was ‘Pictures that educate, enlighten and entertain.’ He really believed in that.”

Tim Gray contributed to this report.

(Pictured above: Sam Warner, Albert Warner, Jack Warner and Harry Warner)

SMOKE + MIRRORS + SOUND

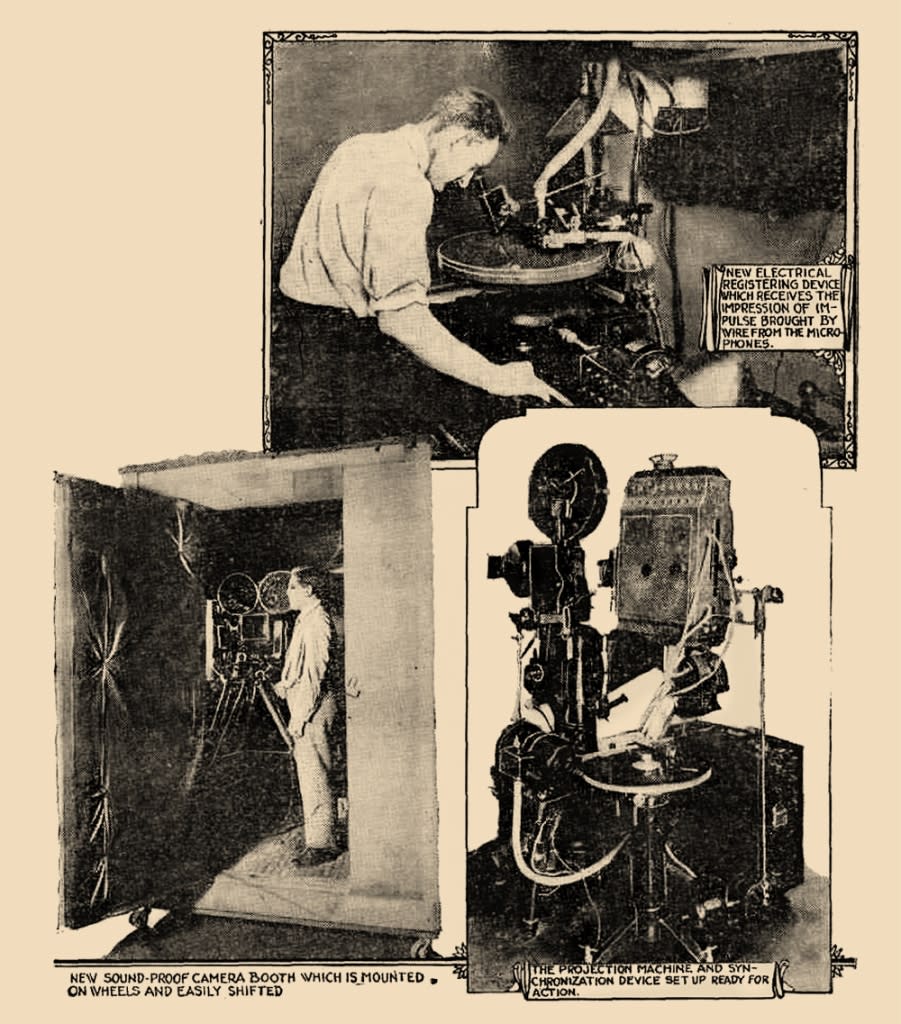

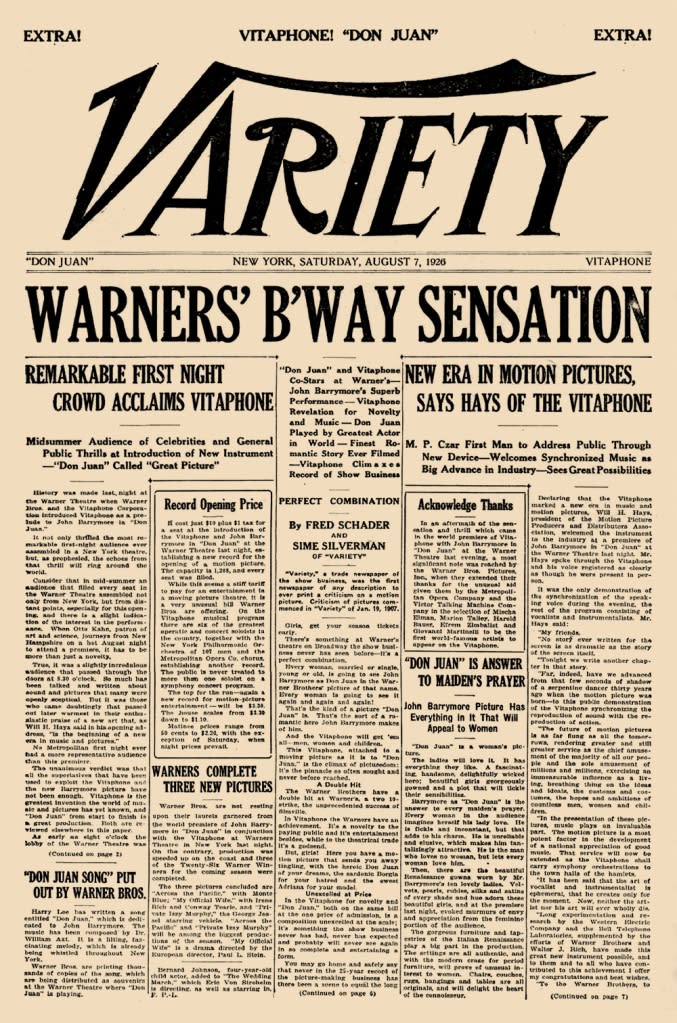

The Al Jolson starrer “The Jazz Singer” changed everything about the movie business. But months before Jolson’s voice rang out in theaters, Warner Bros. delivered the first hint of adding audio to motion pic- tures with the 1926 John Barrymore vehicle “Don Juan.”

The silent film was enhanced by several musical selections and sound effects that were reproduced in theaters by a Vitaphone-built device placed next to the projector. This synchronized-sound technol- ogy was not destined to last long, even though sound was clearly poised to revolutionize movies. Variety made a valiant effort to explain how it all worked with this steampunk-esque graphic that ran in our Aug. 7, 1926, special edition on “Don Juan’s” great leap forward.

Warner Bros. showed off its innovation at a glitzy premiere on Aug. 6, 1926, at the Warner Theatre in Manhattan. The presentation opened with a sound-enhanced short featuring the voice of Will Hays, president of what would become the Motion Picture Assn.

“No story ever written for the screen is as dramatic as the story of the screen itself. Tonight we write another chapter in that story,” Hays told the crowd. “Far, indeed, have we advanced from that few seconds of shadow of a serpentine dancer 30 years ago when the motion picture was born — to this public demonstration of the Vitaphone synchronizing the reproduction of sound with the reproduction of action.”

VIP+ Analysis: What Rivals Can Learn From WBD Streaming Plans

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.