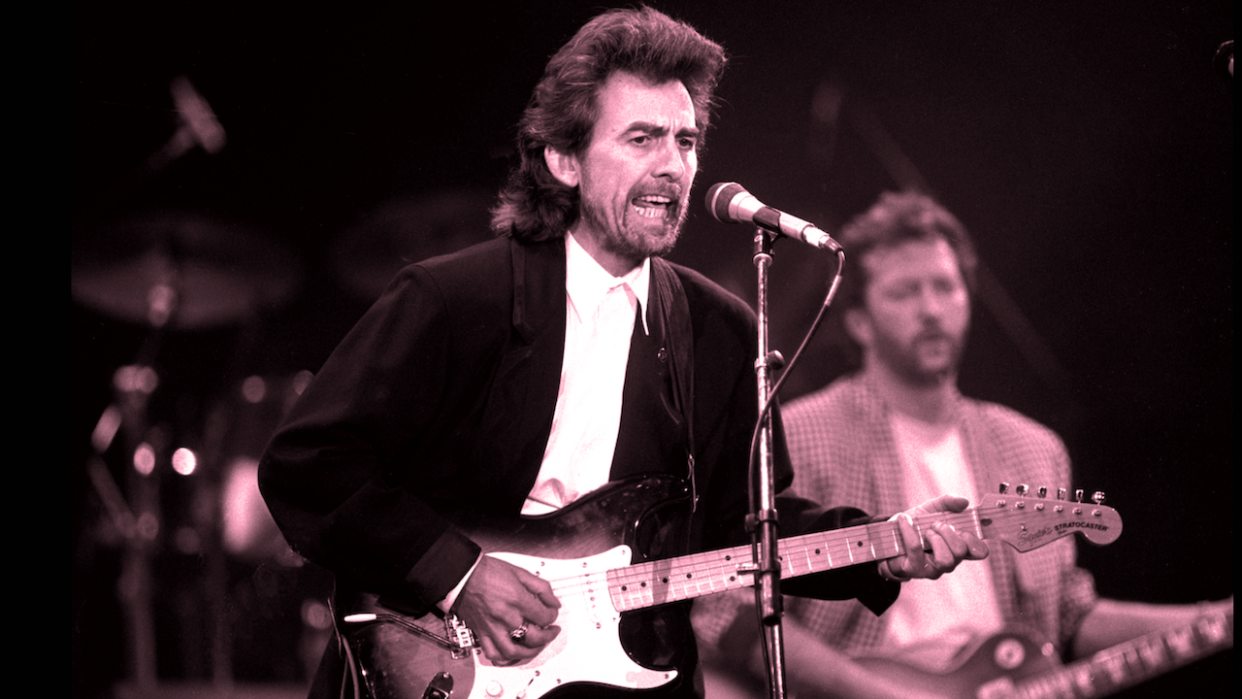

"I wanted Eric Clapton on My Guitar Gently Weeps for a bit of moral support and to make the others behave..." Jamming with Eric Clapton, recording with the Beatles: A long-lost interview with George Harrison

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

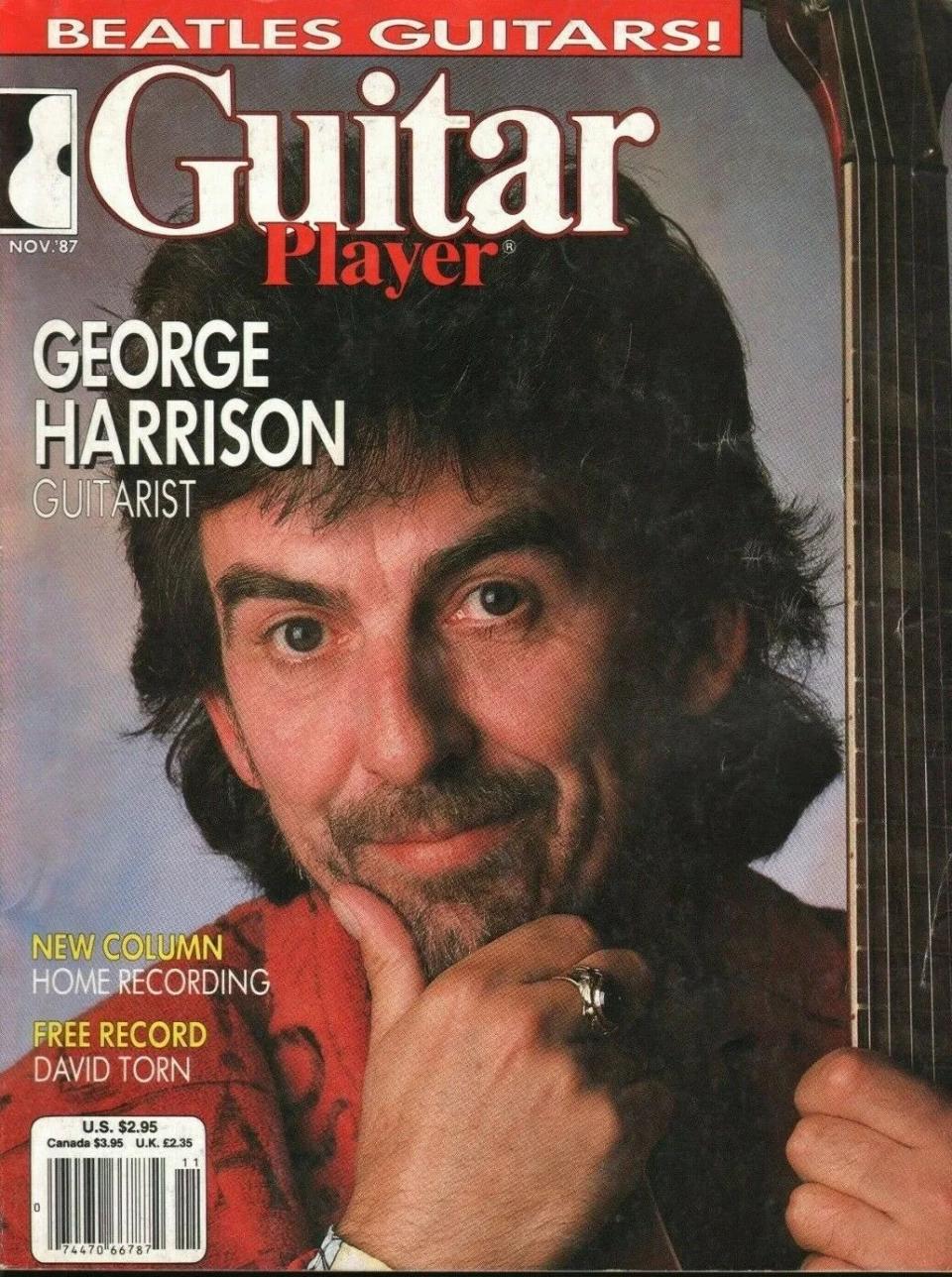

When George Harrison sat down with Guitar Player's then Editor At Large Dan Forte for the cover story of the November 1987 issue, he was promoting the release of his 11th solo album, Cloud Nine. The lead single from the album – a version of the Rudy Clark song Got My Mind Set On You – would take him to number 1 in the Billboard charts but, affable and humble as ever, Harrison was happy to look back over his entire career, including the recording of While My Guitar Gently Weeps, The Beatles' Hamburg days, his love of Gretsch guitars and much more. Here we reprint that interview in full…

With all that's been written about the Beatles and their indelible stamp on music, fashion, and pop culture, they are individually still criminally underrated as musicians. Not only did they inspire a generation to plug in electric guitars and harmonize, but they also influenced how guitar players played, how bassists played, how drummers drummed, and how singers sang. And while each later took turns reinforcing the obvious – that something magical and greater-than-the-sum happened when they played as a band – their separate instrumental contributions can't be overemphasized.

Easily the most overlooked was George Harrison. Continuing (and distilling) the tradition of his melodic rockabilly idols Carl Perkins, Scotty Moore, and James Burton, the youngest Beatle was just coming into his own when Clapton and Beck ushered in the age of the Guitar Hero. George's forte was not extended improvised jamming; he was (and is), however, a supreme melodicist, a sensitive ballad player, a strong rhythm man, a fine acoustic guitarist, and one of electric slide's most distinctive stylists. And to this day, no one's been able to match his range of crystalline tones and textures.

The Beatles' music didn't lend itself to guitar heroics, and vice versa. The antithesis of the guitarist as gunslinger, Harrison was a parts player and a chameleon. From the very beginning, his egoless role (and tone) changed, depending on what the song called for. Just try playing a different 12-string break to A Hard Day's Night, and you'll see that Harrison's compact, worked-out guitar solos were as essential to the group's sound and success as Ringo's unique drumming or their multi-part vocal harmonies.

And if the song called for a Chet Atkins-ish country break (as on I'm a Loser) - or a twangy, Duane Eddy-tinged bass line (It Won't Be Long) or even some pseudo-bossanova on gut-string (Till There Was You) - the group looked no farther than their own lead guitarist, and George never failed to deliver. George may downplay his 6-string abilities, pointing out that he's not the kind of player "who could just pop in on anybody's session and come up with the goods," but he did exactly that during his decade with the Beatles. He was everything anyone could hope for in a studio player and then some.

George Harrison was born on February 25, 1943, in Liverpool, England, the port out of which his father, a merchant seaman, was based. At 13 George bought his first acoustic guitar. He hated school, but at least one fortuitous event took place there: He met Paul McCartney. The subsequent history of the Beatles has been reported innumerable times. Here is the brief version: With drummer Pete Best and bassist Stu Sutcliff (Paul then played guitar), the group began playing Liverpool's Cavern Club in 1960, the same year they made their first trip to Hamburg, Germany, where they played eight or more hours per night.

Six months later they made their recording debut, backing singer Tony Sheridan. During the next year, Paul became full-time bassist, Brian Epstein became the group's manager, and the Beatles were auditioned and turned down by Decca Records (in favor of Brian Poole & The Tremeloes).

After a few more months in Hamburg, the quartet auditioned for producer George Martin, at whose urging Best was replaced by Ringo Starr. Their first single, Love Me Do backed with P.S. I Love You, was recorded in September '62, followed by the release of Please Please Me a few months later. By the end of 1963, the Beatles had released their first two albums and given a Royal Command Performance, and their reputation was just beginning to spread to America.

At the end of March 64 they had simultaneously secured Billboard's singles chart's top five: Can't Buy Me Love, Twist & Shout, She Loves You, I Want to Hold Your Hand and Please Please Me, respectively, along with seven more titles in the Hot 100.

By the end of 1966 the Beatles had released seven albums in England, starred in the feature-length movies A Hard Day's Night and Help!, and played their last live show (San Francisco's Candlestick Park, August 29, 1966). George had also begun studying with sitar master Ravi Shankar in India.

The 1967 concept album masterpiece Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band and British TV film Magical Mystery Tour took the experimental nature of Revolver several steps further. The following year saw the formation of Apple Corps and Harrison's first solo project, the film score to Wonderwall, which he produced in Bombay with a cast of Indian musicians and himself (playing guitar under the name Eddie Clayton).

For The Beatles, the double "White Album" released in November '68, George enlisted Eric Clapton to play the solo on his composition While My Guitar Gently Weeps. The following January the Beatles began work on the filming and recording of Let It Be, although it was not released until May 1970. During the interim, George released his experiments with synthesist Bernie Krause as Electronic Sound, and the band recorded Abbey Road. George also shared guitar chores with Clapton on Delancy & Bonnie's U.K. tour. By the end of 1970 the only place the Beatles got together was in court; their musical working relationship was ended.

While he may have toiled in the shadow of Lennon and McCartney for most of his life as a Beatle, Harrison quickly dispelled any notion that he was dependent on them with 1970's All Things Must Pass, a triumphant three-record boxed set co-produced by Phil Spector. In 1971, Harrison brought together Bob Dylan, Leon Russell, Eric Clapton, Ringo Starr, Billy Preston, Ravi Shankar, and others for the Concert for Bangladesh at New York's Madison Square Garden, the first rock concert staged to benefit famine victims.

Living in the Material World, from 1973, contained the hit Give Me Love. In the fall of '74 Harrison formed a band encompassing fusion saxophonist Tom Scott's L.A. Express, Billy Preston, Ravi Shankar, and an orchestra of Indian musicians to tour America. Between then and his two-night appearance at the Prince's Trust concert in London in 1987, the only official onstage appearance Harrison made was in 1977, when he joined Paul Simon on Saturday Night Live to play acoustic versions of Beatles and Simon & Garfunkel songs. The program received the highest ratings in the show's history. While he has released several more solo efforts, his energies have turned more towards filmmaking - producing, among others, Monty Python's Life of Brian and Time Bandits.

Do you still practice the sitar?

I do, yeah. I've got a nice sitar in my guitar room, and I pick it up occasionally. I'm still fascinated it's such a great-sounding instrument. I mean, I'm no way very expert at it. The same with a guitar. You have to really play and practice if you're going to be any good, and I don't do that. Even with the sitar, I didn't touch it for years, but just over the last two years I got it out and all tuned up again. I really enjoy it.

During the five years between Gone Troppo [his previous solo album, 1982] and Cloud Nine, did you play the guitar much?

I tend to just use the guitar to write tunes on. And then because I've got a studio in my house – to make demos. Like through those five years I never really stopped writing.

Clapton has mentioned you as an influence, and there was that period where you both sounded very similar. Something is not all that far removed from, say, Wonderful Tonight.

Yeah, I love Eric. I love the touch he has on his guitar. When he comes over to play on my songs, he doesn't bring an amplifier or a guitar; he says, "Oh, you've got a good Strat." He knows I've got one because he gave it to me [laughs]. He plugs in, and just his vibrato and everything... he makes that guitar sound like Eric. That's the beauty of all the different players that there are. There are players who are better than each other, or not as good, but everybody's got their own thing. It's like a 12-bar blues. You can't do a 12-bar the same way twice, so they say.

There's things that Eric can do where it would take me all night to get it right. He can knock it off in one take because he plays all the time. But then again, when we're listening to some of my slide bits, he'll look at me, and I know he likes it. And that, for me, if Eric gives me the thumbs up on a slide solo, it means more than half the population.

It seems odd that the one real guitar-solo-vehicle you wrote with the Beatles, While My Guitar Gently Weeps, was the only Beatles song where you had Eric Clapton play the solo. From a producer's point of view, that's a perfect move, but as an artist with an ego, didn't you want your own stamp on that solo?

No, my ego would rather have Eric play on it. I'll tell you, I worked on that song with John, Paul, and Ringo one day, and they were not interested in it at all. And I knew inside of me that it was a nice song. The next day I was with Eric, and I was going into the session, and I said, "We're going to do this song. Come on and play on it." He said, "Oh, no. I can't do that. Nobody ever plays on the Beatles records." I said, "Look, it's my song, and I want you to play on it." So Eric came in, and the other guys were as good as gold because he was there.

Also, it left me free to just play the rhythm and do the vocal. So Eric played that, and I thought it was really good. Then we listened to it back, and he said, "Ah, there's a problem, though; it's not Beatle-y enough" – so we put it through the ADT [automatic double-tracker], to wobble it a bit.

Were many of the guitar solos cut live?

Yeah. In those days we only had, like, 4-tracks. On that album, the White Album, I think we had an 8-track by then, so some things were overdubbed, or we had our own tracks. I would say the drums would probably all be on one track, bass on another, the acoustic on another, piano on another, Eric on another, and the vocal on another, and then whatever else. But when we laid that track down, I sang it with the acoustic guitar with Paul on piano, and Eric and Ringo that's how we laid the track down. Later, Paul overdubbed the bass on it.

That's the album people always point to as being the first sign of the Beatles separating – with the different songs really exhibiting more of the individual composer's style, rather than the band's. But it still has an organic, band feel- with various members trading instruments.

Yeah, yeah. We still all helped each other out as much as we could.

Speaking of collaborations, on Cream's Badge did you write the words and Clapton the music? Who played the guitar through the Leslie on the bridge?

That's where Eric enters. On the record, Eric doesn't play guitar up until that bridge. He sat through it with his guitar in the Leslie [rotaring speaker], and I think Felix somebody [Pappalardi] was the piano player. So there was Felix, Jack Bruce, [drummer] Ginger Baker, and me – I played the rhythm chops – and we played the song right up to the bridge, at which point Eric came in on the guitar with the Leslie. And then he overdubbed the solo later.

Let me see, I wrote most of the words, Eric had the bridge, definitely, and he had the first couple of chord changes. He called me up and said, "Look, we're doing this last album, and we've each got to have our song by Monday." I finished the verses off, and he had the middle bit already, and I think I wrote most of the words to the whole song – although he was there, and we bounced off of each other. The story's getting a bit tired now, but I was writing the words down, and when we came to the middle bit I wrote Bridge. And from where he was sitting, opposite me, he looked and said, "What's that - Badge?" So he called it Badge because it made him laugh.

It sounds as much like a Beatles song as a Cream song.

Yeah, well, that's because he did it with me instead of with Jack. Like, I wanted Eric on Guitar Gently Weeps for a bit of moral support and to make the others behave, and I think it was the same reason he asked me to play on that session with them.

In the Beatles, you always seemed to play solos as mini compositions and use different sounds and techniques according to whatever the song called for. That attitude tends to get overlooked a lot with so much importance placed on pyrotechnics.

Yeah, worked-out solos. I think that was largely because, like on the early records, we went straight onto mono or stereo. Then we got a 4-track. But a lot of those takes, we had to do everything at the same time, or as much as possible. So we'd say, "These guitars are gonna come in on the second chorus playing these parts, at which time the piano will come in, too, on top." And we'd have to get the individual sound of each instrument, and then the balance of those to each other, because they were all going to be locked together on one track. Then we had to do the performance, where everybody got their bit right. I think it was maybe to do with that, where we'd worked out parts.

Listening to some of the CDs, there are some really good things, like And Your Bird Can Sing, where I think it was Paul and me, playing in harmony – quite a complicated little line that goes right through the middle eight. We had to work those out, you know. In the early days, the solos were made up on the spot, or we'd been playing them onstage a lot.

What do you think of the Beatles on compact disc?

I'm not so keen on the sound on the CDs; I think I prefer the old mixes, the old versions. I think CDs are good on all this new stuff, but I don't know about the old stuff put on them.

But those early sounds, I hated them. I remember midway through the '60s there'd be all these American groups we'd bump into, and they'd say, "Hey, man, how did you get that sound?" And I realized somewhere down the line, I was playing these Gretsch guitars through these Vox amps, and in retrospect, they sounded so puny. It was before we had the unwound third string, that syndrome, and because it was always done in a rush and you didn't have a chance to do a second take, we just hadn't developed sounds on our side of the water.

I mean, listening to James Burton playing them solos on the Rick Nelson records, and then we'd come up with this stuff, it was so feeble. I got so fed up with that, and that was the time that Eric gave me that Les Paul guitar. And that gets back to the story of Guitar Gently Weeps: It was my guitar that was gently weeping – he just happened to be playing it.

On My Guitar Gently Weeps, it was my guitar that was gently weeping – Clapton just happened to be playing it.

The White Album was a definite departure in terms of guitar sounds with more volume and fuzz. Was that a product of the times and the themes of those songs?

It was partly that and the type of bands that were around. We started out like this little group in mono; we just played a couple of takes, and that was it. And the engineers who worked in Abbey Road had been doing Peter Sellers records or skiffle. Nobody had had any experience like in America. America was always ahead, and we always looked to America for the sounds and the groovy players. We felt just like a lucky little group. We knew we had something good to offer, but we were quite modest. The situation we were in was this old equipment, but we were happy with it in those days; we were just happy to be in the studio.

And as things developed, we probably got a 4-track when America was all getting their 8-tracks, going to 16. Then we got an 8-track when they were all into 24. We were always that far behind, but this is the thing that puts me against a lot of the music now. Everybody's got 48 channels and MIDI'd and MAXI'd and 89,000 pedals on their guitars and everything and yet, it's still not as good as That's All Right, Mama by Elvis Presley or Blue Suede Shoes by Carl Perkins, or Chuck Berry or Little Richard, Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, the old Everlys. You can go through all that stuff – they had greater sounds.

So when the pedal syndrome came along, I couldn't be bothered with that. I got into the thing of thinking, "Now, if I can just get my guitar in tune and get it so that I can play jing-jinga-jing and a few little licks and it sounds nice, that'll do me." I ain't doing acrobatics with all these things.

[It's like] when Carl Perkins talks about hearing Les Paul and learning to play like that [not knowing that Les Paul used tape echo and overdubs]. Well, we used to do that, in a way. Like the slap echo that was on the old Sun records, Carl's and Elvis' - we used to sing like that, sing the tape echo, or try to play it. We thought, "Well, that must be the drummer drumming with the sticks on the bass strings" [imitates a slap bass line]. We were naive; we didn't have a clue. Even on Abbey Road we used to have to invent ways of keeping it interesting or making new sounds. We'd think, "Well, let's be Fleetwood Mac today," and we'd put a lot of reverb on and pretend to be Fleetwood Mac.

[In another interview from 1987, George confirmed that it was the track Sun King he was referring to: "At the time, Albatross was out, with all the reverb on guitar. So we said, 'Let's be Fleetwood Mac doing Albatross, just to get going.' It never really sounded like Fleetwood Mac... but that was the point of origin."]

There's a volume pedal effect you got on songs such as Yes It Is and Wait and I Need You. Were you using a volume pedal back then?

I think I tried to. There was a guy in Liverpool [most likely Colin Manley – Ed] who used to go to school with Paul and I, and he was in a hand called The Remo Four and played with Billy J. Kramer. And he got all that stuff and could play all those Chet Atkins ones where you can play both tunes at the same time like Colonel Bogey. He had a volume pedal, and I think we tried that, but I could never coordinate it. So some of those, what we'd do is, I played the part, and John would kneel down in front of me and turn my guitar's volume control.

That's like Peggy Sue by Buddy Holly. He had a guy kneeling down to switch his Strat to the rear pickup for the guitar solo.

Yeah, that's great stuff, isn't it? That's still one of the greatest guitar solos of all time.

At some point, after the Beatles, you switched your solo playing almost exclusively to slide.

Right. In the '60s, I forget exactly which years, there was a period where I really got into Indian music. I started playing the sitar and hanging out with Ravi Shankar, and I took some lessons for a couple of years. Then after that period, I thought, "Well, really, I'm a pop person. I'm neglecting the guitar and what I'm supposed to do." I knew I was not going to be a brilliant sitar player, because I'd already met a thousand of them in India, and Ravi thought one of them was going to make it as a really top class player. I still play the sitar now for my own amusement, and I enjoy it, but I thought I'd better get back on the guitar.

By that time there were all these people like 10 years old playing brilliantly. I just thought, "God, I'm so out of touch. I don't even know how to get a half-decent sound." The result of that was I thought, "Oh, I'll see what happens here with this slide." And it sort of sounded funkier than what I could with my fingers at this time. It developed from that, without me realizing it. Then people would come up and say, "Would you play slide on my record?" I'm thinking, "Really? Are you sure?" Then, I don't know, I started hearing people sort of imitating me doing slide, which is very flattering. But, again, like I was saying about the sound – "How did you get that sound?" – I didn't think it was that good.

Do you think that Indian music and the sitar influenced your approach to slide?

Definitely. Because you can get all those quarter-tones. Yeah. See, I never really learned any music until I sat down with Ravi Shankar with the sitar. He said to me, "Do you know how to read music?" Oh no, here we go again. Because I felt like there were really much better musicians who deserved to be sitting with this guy who's such a master of the instrument. I started getting panicky. I said, "No, I don't know how to read music." He said, "Oh, good because it's only going to influence you."

Then I did learn how to notate in what they call the sufi system, which is like the Hindustani classical way of notating. It was the first time I had any discipline, doing all these exercises. They show you how to bend the string. I talk briefly about it in I Me Mine. What they call hammering on with the guitar, there's exercises for that, and bending. Because on a sitar, from the first string, you've got a good two inches of fret, and you're pulling it down. It's like Albert King playing left-handed, and he can pull that E string right across the neck.

It's amazing how that sounds different from a right-handed player pushing the string from the opposite direction.

It's because you've got more strength in your hand, I think, to pull it that way than you have to push. So that was the first time I actually learned a bit of discipline doing all these little things in conjunction with what you do with your right hand, the stroke. If you strike the string down, it's called da, and if you hit it up, it's called ra. I'd be trying to practice one of these complicated exercises, thinking I'd just be getting it, and Ravi would say, "No, no. Ra. Ra." I'm hitting it one way instead of the other – you know, "Does that matter at this stage?" We don't have that sort of frame of reference in guitar.

Then with slide what I could do is actually hit the string with one stroke and [hums a scale] – do a whole little wobbly bit. And because of the Indian stuff, it made me think a bit more about the stroke side to it, and I realized there's so many different ways of playing, say, a three-note passage. You can strike it and go down with one stroke; you can strike it each time – there's a million permutations of that one thing. The Indian music also gave me a greater sense of rhythm and of syncopation. I mean, after that I wrote all these weird tunes with funny beats and 3/4 bars, 5/4 bars. Not exactly commercial, but it got inside me to a degree that it had to come out somewhere.

When I did that tour in '74 with all the Indian musicians, I had Robben Ford on guitar. I think he's brilliant because not only is he a great blues player and rock player, but he really got into playing all the Indian stuff, too.

The sound of the Beatles was influenced a lot by the changes in instruments – a lot of which were simply because some company gave you guys new guitars. Did Rickenbacker give you a 12-string?

Yeah, I got number two. This friend of mine in England who takes care of guitars, Alan Rogan, just found out that the Rickenbacker 12-string of mine is the second one they made. The first one they gave to some woman, and the second one is the one I got. I got another one from them with the rounded cut-aways, but I'm glad to say that the one that went missing – I got a lot of stuff stolen or lost – wasn't that original one. That guitar is really good. I love the sound of it and the brilliant way where the machine heads fit so that even when you're drunk you can still know what string you're tuning.

On If I Needed Someone, is that the Rick 12-string capoed up?

If it's not in D, it must be. It was written in D nut position [capoed at the 5th fret]. The opening to A Hard Day's Night is also that Rickenbacker 12-string. And in fact on the new album, Fish On The Sand is the Ricky 12-string

What's your main guitar for slide?

I'm so dumb, really. It takes me years to figure things out. But through Ry [Cooder] – I really like his slide – I realized that you jack the bridge up a bit and you put thicker-gauge strings on it, so it doesn't clatter around. So I have my psychedelic Strat set up like that now.

What were the band politics in the instances where one of the other Beatles would play lead guitar? Didn't Paul play the lead on Taxman, for instance?

Well, with certain things like that, in those days, for me to be allowed to do my one song on the album, it was like, "Great. I don't care who plays what. This is my big chance." So in Paul's way of saying, "I'll help you out; I'll play this bit," I wasn't going to argue with that. There's a number of songs that Paul played lead on, or John did, but people just think because it said "lead guitar" it was all me.

Paul played slide actually on Drive My Car – that wasn't me. But likewise, I played bass on some tunes, and we all did various things. And to go track by track, like I think John did at some point – "I did this and I did that" – we all contributed a lot to it, and it doesn't matter to me. Like I said, if there's something where Eric can do it, and it's going to make my song sound better, it doesn't matter to my guitar player's ego. Same with Paul. I was pleased to have him play that bit on Taxman. If you notice, he did like a little Indian bit on it for me. And John played a brilliant solo on Honey Pie from the White Album – sounded like Django Reinhardt or something. It was one of them where you just close your eyes and happen to hit all the right notes. Sounded like a little jazz solo.

Most of the articles and interviews on the Beatles spend more time on the Beatlemania and seldom discuss the four of you as musicians – for instance, what first attracted you to taking up the guitar?

Exactly, right. My earliest recollection is that my dad used to go away to sea in the merchant navy, and sometime when I was a little boy he brought a wind-up gramophone that he bought in New York, and he had all these records. The old 78s with the big needles. And he had Jimmie Rodgers. Not the guy who sang Honeycomb, but the old Jimmie Rodgers. And I just loved that, just the sound of those old acoustic guitars recorded really roughly. I don't know, something just appealed to me. I'll tell you who was really big in England was a guy from Jacksonville, Florida: Slim Whitman. And he did all these tunes like Rose Marie, and he was on the radio and had a lot of hit records in England.

I heard there was a guy, when I was about 12 or 13, who went to the junior school I went to, and he was selling this guitar. I just went and bought it off him. Cost me three pounds, 10 shillings. This was when it was $2.50 for a pound, so it was about $10. Just a little cheap acoustic guitar, but I didn't really know what to do with it. I noticed where the neck fitted on the box it had a big bolt through it, holding it on. I thought, "Oh, that's interesting." I unscrewed it, and the neck fell off [laughs]. And I was so embarrassed, I couldn't get it back together, so I hid it in the cupboard for a while. Later my brother fixed it.

Then there was this big skiffle craze happening for a while in England – which was Lonnie Donegan. He set all them kids on the road. Everybody was in a skiffle group. Some gave up, but the ones who didn't give up became all those bands out of the early '60s. Lonnie was into, like, Lonnie Johnson and Lead Belly, those kind of tunes. But he did it in this sort of very accessible way for kids. Because all you needed was an acoustic guitar, a washboard with thimbles for percussion, and a tea chest – you know, a box that they used to ship tea in from India – and you just put a broom handle on it and a bit of string, and you had a bass.

We all just got started on that. You only needed two chords: [hums] jing-jinga-jing, jing-jinga-jing, [hums lower] jing-jinga-jing, jing-jinga-jing [laughs]. And I think that is basically where I've always been at. I'm just a skiffler, you know. Now I do "posh skiffle." That's all it is. That's why I've always been embarrassed at the idea of being in Guitar Player magazine. It's just posh skiffle.

Once you got electrified, who were your main influences?

Once we got going it was like Heartbreak Hotel, hearing that early Elvis stuff, Carl Perkins – I don't recall which order they came in – the Everlys, Eddie Cochran. You know, I've always wanted one of them orange Gretsches with a big "G" stamped on it. I finally got one. My wife got me the one I used on the Carl Perkins program for Christmas a couple of years ago – except it didn't have the "G" on it. I mean, I just loved that stuff. And the first time I ever saw a photograph of Buddy Holly with that Strat – I'm sure it was the same for millions of kids – but, you know, you cream yourself, your pants, looking at this. Wow! When I was in school, I was always bad in school, I didn't like it, I'd always just sit in the back. But I've got some of my books still, from when I was about 13 and there's just drawings of guitars and different-style scratchplates, always trying to draw Fender Stratocasters.

Was Cry For A Shadow, the instrumental you wrote with John, written in reference to the Shadows?

We always used to have a little joke on the Shadows. Because in England, [singer] Cliff Richard and the Shadows were the biggest thing, they were like the English version of the Ventures. And it was a time when – we were lucky because we didn't get into it – everybody had matching ties and handkerchiefs and suits, and all the lead guitar players had glasses so they looked like Buddy Holly, and they all did these funny walks while they were playing.

Well, we went to Hamburg and got straight into the leather gear. And we were doing all the Chuck Berry and Little Richard and that kind of stuff – and just foaming at the mouth because they used to feed us these uppers to keep us going, because they made us work eight or ten hours a night. So we used to always joke about the Shadows, and actually in Hamburg we had to play so long, we actually used to play Apache or whatever was their hit. But John and I were just bullshitting one day, and he had this new little Rickenbacker with a funny kind of wobble bar on it. And he started that off, and I just came in, and we made it up, right on the spot. Then we started playing it a couple of nights, and it got on a record somehow. But it was really a joke, so we called it Cry For A Shadow.

But you don't consider yourself to have been influenced by the Shadows' Hank Marvin, as was the case with most English guitarists of that period?

Naw, no. Although Hank is a good player – I would certainly not put him down – and I did enjoy the little echo things they had and the sound of the Fenders, which they started out on. But, to me, Walk, Don't Run, the Ventures – I just always preferred the American stuff to the English. So I wasn't influenced by him at all. I'm more influenced by Buddy Holly. I mean, right till this day I could play you the Peggy Sue solo any time, or Think It Over or It's So Easy. I knew all them tunes, and Eddie Cochran stuff. Right before Eddie Cochran got killed, I was lucky enough to see him when he came to play the Liverpool Empire, and he was hot, I tell ya. He started the show with What'd I Say and Milkcow Blues. He had his unwound third string and his Bigsby going – he was real cool.

I read that after the Beatles appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show, Gretsch sold 20,000 guitars a week or something. I mean, we would have had shares in Fender, Vox, Gretsch, and everything, but we didn't know. We were stupid.

Why did you end up with a Gretsch instead of a Strat, considering Buddy Holly's influence?

What happened was, my first guitar was this little cheap acoustic I mentioned, and then I got what they call a cello-style, f-hole, single-cutaway called a Hofner which is like the German version of a Gibson. Then I got a pickup and stuck it on that, and then I swapped that for a guitar called a Club 40, which is a little Hofner that looked like a solid guitar but was actually hollow inside with no soundholes.

Then this guitar came along called a Futurama. It was a dog to play, it had the worst action. They tried to copy a Fender Strat. It had a great sound, though, and a real good way of switching in the three pickups and all the combinations. But when we got to Hamburg, there was this Fender Strat, which was the first real Strat I'd ever seen in person, other than a photo. I was going to buy it the next day, and there was this other band called Rory Storm & The Hurricanes which Ringo was with. And the guitar player ran out and got his money, and he got it. The next day when I got up there, it had gone, and he was up there playing it [smiles, strumming air guitar]. I thought, "Aw, shit!"

Then we started making a bit of money, because I saved up 75 pounds, and I saw an ad in the paper in Liverpool, and there was a guy selling his guitar. I bought it; it was a Gretsch Duo Jet – which is now on my new album cover. It was a sailor who bought it in America and brought it back. It was like my first real American guitar, and I'll tell you, it was second-hand, but I polished that thing; I was so proud to own that. That was the reason I think when we went to the States to play the Ed Sullivan Show, Gretsch gave me a Gretsch that I used on the show. I didn't realize at the time because if I had, I'd have 20 Gretsches right now, with square ones, round ones, fur ones, and all them like Bo Diddley – but I read somewhere that after the Beatles appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show that Gretsch sold 20,000 guitars a week or something like that. I mean, we would have had shares in Fender, Vox, Gretsch, and everything, but we didn't know. We were stupid.

Nevertheless, they gave me a couple of Gretsches, which was very nice of them, and I wish they were still in business, the original company, because I've got some great ideas for what they should do. I mean, all these companies – I suppose it's the same as motor cars. They're so into making little wedgie turbos, but what about all them with the big wings? They could still put on all those high-tech switches and pickups, possibly, but you can't beat that Strat and those old pickups they had on it, I don't care what you say. The same with some of those designs of those older guitars. I mean, that book American Guitars is fantastic. I just look at that, and certain ones, like that D'Angelico with the real art-deco scratchplate. I'm still a kid when it comes to guitars. Anyway, Gretsch gave me those guitars, and I was pleased to have them, but I never really got the one I wanted, which was the orange well, it's called the Chet Atkins, but to me it's the "Eddie Cochran" model.

In the past few years, when you were concentrating more on filmmaking, did you see yourself primarily as a guitarist still, as a songwriter, a filmmaker, or what?

I don't really see myself as a songwriter or a guitarist or a singer or a lyricist or even a film producer. All of those are me, in a way just like I like gardening, digging holes and sticking trees in. But I'm not really a gardener, just like I'm not really a guitarist but I am. If I plant 500 coconut trees, I'm sort of a gardener, aren't I? And if I play on records and stuff, then I'm a guitarist. But not in the sense like, say, B.B. King or Eric Clapton, who play constantly and keep their chops together and are really fluid. You have to play all that time to keep good, and in that respect... you know, I'm not trying to put myself down, but the reality is I'm okay. I mean, I've sat with people who are just learning the guitar and showed them some chords and a few things – and I realized I do know quite a lot about guitar; I've absorbed quite a lot over the years.

But I've never really felt like I was a proper guitar player. You see all these guys with their chops together, with charts showing how they did it. In the sense of being a guitarist who works and plays, and who could just pop in on anybody's session and come up with the goods, I'm not that kind of player. I'm just a jungle musician, really.

This interview was originally published in Guitar Player magazine, November 1987. The Beatles’ 1962-1966 (‘The Red Album’) and 1967-1970 (‘The Blue Album’) collections are out now in 2023 Edition packages