Villains Always Blink Their Eyes: A New Book Captures the Timeless Mean Charisma of Lou Reed

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

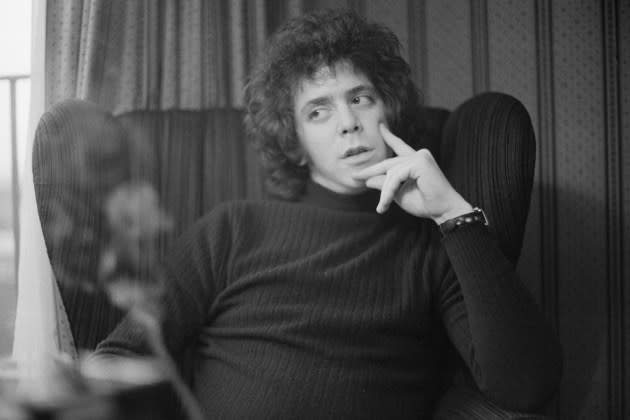

Lou Reed died 10 years ago, in October 2013. But since then, he’s just become a more massive, more famous, more influential figure. His life is one of the strangest music stories ever. Will Hermes tells the whole epic tale in his new biography, Lou Reed: The King of New York. For most people, he’s the black-leather avant-garde rock & roll poet who symbolized NYC with his band the Velvet Underground, in the Warhol Factory scene of the 1960s. “I’m Waiting for the Man,” “Sister Ray,” “Sweet Jane” — these are songs that capture the mean rush of the city.

Lou had a legendary run in the 1970s and the 1980s, with the glam decadence of Transformer, the nihilist noise of Metal Machine Music, the CBGB punk of Street Hassle, the noir confessions of The Blue Mask. In the Nineties, he married another formidable NYC artist — Laurie Anderson, who’d barely heard of him. Mr. White Light/White Heat, the abrasive madman who sneered “Walk on the Wild Side” and “Vicious,” somehow became rock’s most unlikely elder statesman. The world became a more Lou Reed place. His drugged-out ballad “Perfect Day” turned into a beloved wedding standard. As Hermes notes in the book, we live in a world where the taste-the-whip BDSM orgy “Venus in Furs” can be used in a TV commercial for tires.

More from Rolling Stone

Patrick Stewart: The Night I Worried I May 'Kill Paul McCartney'

John Mayer Believes Dead & Co. Loves the Music So Much They Will Play More Shows

Wes Anderson Speaks Out Against Roald Dahl Book Censorship in Venice

Hermes, a longtime music critic and Rolling Stone contributor, wrote the definitive story of NYC’s 1970s music explosion, Love Goes to Buildings on Fire. But he’s the first biographer to have access to the New York Public Library’s giant new Reed archives. There have been great bios before (Anthony DeCurtis’ 2017 Lou Reed is a real banger), but no matter how well you know the man and his music, there’s so much more to him that’s never been revealed until now. This book has the menace and allure of Reed’s finest work — a fascinating, addictive, head-expanding rush into the unknown.

Hermes spoke to Rolling Stone about Lou Reed’s life, writing the bio of a legend, why Velvet Underground drummer Mo Tucker always called Lou “Honey Bun,” and why Reed remains such a timeless icon. As Hermes says, “He was fighting the good fight, and very often, he sensed it was with himself.”

Where did the Lou Reed book begin for you?

When he died, in 2013, the outpouring of grief was really moving. I was so moved by the way Lou Reed touched people. And ultimately, when the idea came to do the book, that was the seed for me: What is it about Lou Reed that touches people so deeply? He’s a complicated guy for sure, but his work reaches people and speaks to their identities in so many ways. So I wanted to make it the story of a life, so that people could empathize with him, the way Reed empathized with people in his best songs.

His death really hit home for people.

Once he passed, I wanted to figure out why people felt so strongly about his work. So I started at the beginning. The first thing I did was go to the Freeport Public Library and research the town of Freeport, Long Island. He really identified as being a writer, and I wanted to dig into that. So I went up to Syracuse University and found the zines that he did, and tracked down his college buddies. They did the Lonely Woman Quarterly, in 1962. There were three pretty fat mimeographed issues, with poetry and fiction by Lou Reed.

He studied writing with the poet Delmore Schwartz. Lou was a storyteller, a fiction writer. Schwartz hated rock & roll — he called it “cat-gut music.” But even though Delmore always told him, you can’t do poetry in pop songs, Lou was just the kind of guy to say, “I can fucking do it. Watch me.”

But I got a story from a classmate of Reed’s in creative writing. He told me a story about the three of them going to the Orange Bar near the Syracuse strip, getting hammered, in January 1964. There was a new single on the jukebox — The Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” None of them had heard the Beatles before, but they just kept feeding nickels into the box to play this song over and over. Delmore Schwartz, Lou Reed, and this guy singing along all night, then walking home while it snowed, still singing the song.

How did you become a Lou fan?

My first exposure was hearing Rock & Roll Animal on the radio, as a 13-year-old dirtbag. That was his most popular record, radio-wise, as an adolescent getting into rock. In college, I became a Velvet Underground fanatic. I came of age in the Eighties, when he always was doing interesting stuff. Some of the albums were better than others, that’s for sure. But even the worst records had one or two great songs.

I also feel like his later years were so fascinating. Laurie Anderson, I find her to be really one of the most fascinating artists of the last 50 years. She’s every inch his equal as an art-maker. It was so cool that the two of them got together and became a team, even though they were still doing their own thing. That’s really inspiring, so I wanted to learn more about that. I love his experimental musical theater pieces with Robert Wilson. And Lulu, the project with Metallica. That has maybe his greatest latter-day song, “Junior Dad,” which never fails to move me. I marvel at that whole project.

The Velvet Underground have a timeless appeal to new fans. Every generation gets into them. It’s weird how their afterlife is so much like the Grateful Dead.

Well, the Dead were another band that had an avant-garde composer playing bass, and a poet writing lyrics. So there are a lot of parallels there. But there’s always something different about Lou.

Robert Hunter was writing pastoral Americana. He was writing about rivers and trains.

Lou was a subway guy. That was his train of choice. But there’s a tenderness to his songs, and that’s one reason people feel a personal connection. He really built work for the ages. There are so many surprising and moving things that I found out about his vulnerability and his self-doubt. Towards the end of his life, he would say, “I really don’t want to be forgotten.” He thought his work would just disappear, and people would say, “That doesn’t matter anymore.” It’s surprising for a guy who projected being so cocky, so aggro.

It was a surprise to see all the greeting cards from Mo Tucker. He saved every one, and she wrote a lot. She always began her cards, “Dear Honey Bun.” Their friendship had ups and downs over the years, but it was surprising how it lasted. Bob Dylan didn’t really have a Mo Tucker in his life. He didn’t have someone he played with in his early twenties who kept writing him letters starting, “Dear Honey Bun.”

It made me think about how anybody, not just a famous person — there’s always more going on that you don’t know about. People are very complicated and reveal parts of themselves to some people, other parts to other people. And it made me think how everybody’s a transformer. We all transform based on context or the people we’re with, and that’s key to his songs.

Rachel Humphreys is such a huge part of the book. She was his trans partner in the 1970s, but so much about her was unknown until recently.

Rachel is a super-compelling figure. Rachel and Lou had a really deep relationship that lasted years, and she was certainly a muse. There are a number of songs that refer to her, sometimes directly as the end of “Coney Island Baby,” but also I think in songs like “Halloween Parade,” or the album Magic and Loss. She died during the AIDS epidemic in 1990, and was buried in an unmarked grave. I was able to access information that had come to light because of other writers and investigative journalists. I found a couple of people in Rachel’s family who were willing to talk with me, share memories, show me photographs, which was an incredibly moving experience. I wanted to honor an important person in Lou Reed’s life. I hope that this story and other trans stories continue to get told. As much time as I’ve spent on this book, I never believed that I got literally every part of every story. People who are passionate about the topic will come up with new stuff going down the road, and write their own articles and books.

Another key figure is his ex-wife Sylvia Morales. There’s so much mystique about her, from albums like The Blue Mask.

I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say — and a lot of people said this to me straight up — that woman saved his life. She helped him get clean, and she took care of business. I learned this from spending weeks and weeks at the Lou Reed Archive at the Lincoln Center Public Library, going through boxes upon boxes of the most tedious business documents, faxes, everything. She did a lot in terms of getting his work placed in films and TV, especially in Europe. You probably remember the Lou Reed ads for Honda scooters. But look up the Dunlop Tires ad, though — that one is my favorite. A TV ad for Dunlop tires that won awards, for using “Venus in Furs.”

John Cale is a larger-than-life presence in the book, going back to their early days, with all their conflict in the Velvet Underground. He just did an amazing live show in Brooklyn and sang “I’m Waiting for the Man.”

Oh dude, I was there — he’s a force of nature at 81. That man is a giant. John Cale wrote a great memoir with Victor Bockris, What’s Welsh For Zen? — he really does not mince words. He and Lou were both such bad boys. They got into a lot of trouble. But I was watching an interview with Talking Heads on the occasion of the new edition of Stop Making Sense. There was that question: Why did the band break up at the height of their powers? David Byrne was clearly uncomfortable answering. But Tina [Weymouth], God bless Tina, she does not suffer fools — she just said that bands are family, and families feud, and they also love each other. It made me think about Lou and John. I think that was true of them.

People love Lou Reed. That’s always been my sense, through the whole project. People just love that guy. Even if they hated that guy, they loved that guy, because there was just something about him that was so real. He was fighting the good fight, and very often, he sensed it was with himself. And I think everybody can understand that on a certain level. We’ve all got our demons. That’s the ongoing struggle.

Best of Rolling Stone