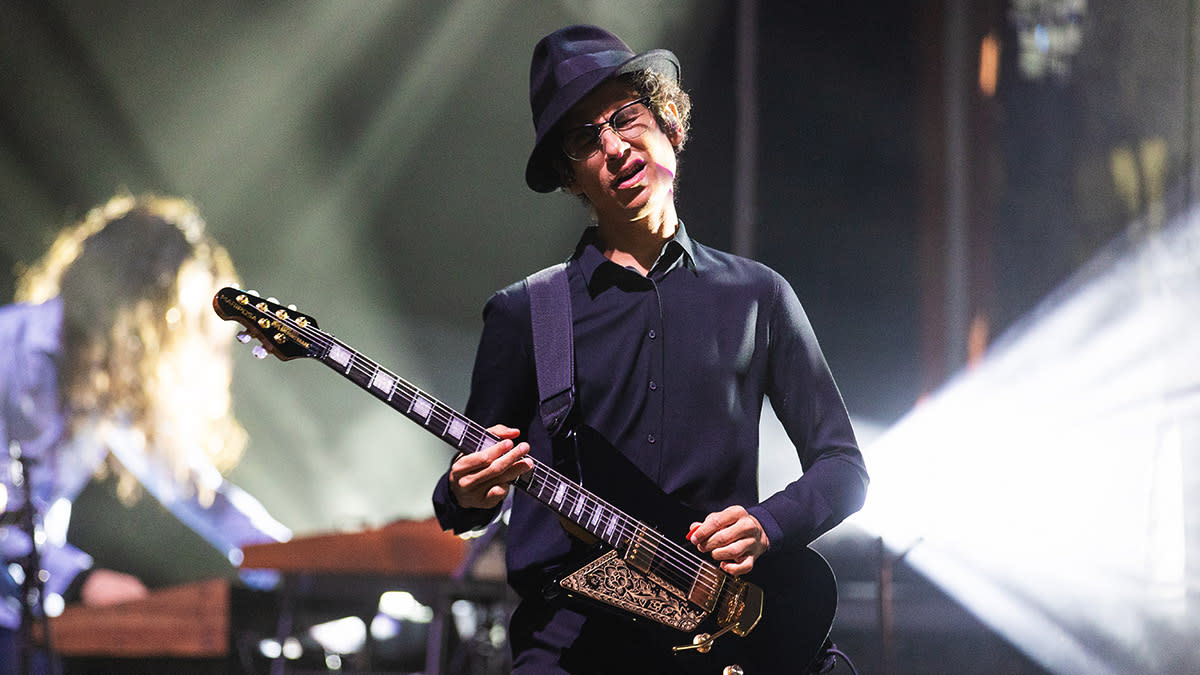

“I’ve never considered myself a guitarist, and I’ve never liked the guitar”: Omar Rodríguez-López is one of electric guitar’s most reluctant heroes – here are his 10 greatest Mars Volta guitar moments

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Back in 2006, Omar Rodríguez-López was a towering, Jimi Hendrix-like figure within the world of modern progressive rock. Guitar World dubbed him one of “The New Guitar Gods,” and he joined a jaw-dropping murderers’ row – Buddy Guy, B.B. King, Eddie Van Halen, Kirk Hammett and John Mayer – for Rolling Stone’s “Guitar Heroes” cover story.

Despite these accolades, the Mars Volta bandleader wasn’t convinced of his own merit on the instrument: “I’ve never considered myself a guitarist, and I’ve never liked the guitar,” he told us.

“I feel like an imposter in a really beautiful, magical place,” he admitted to Rolling Stone during a photo shoot for the aforementioned interview. “And I feel like any minute somebody’s gonna go, ‘That guy!’ and I’m gonna have to leave.”

He’s managed to stick around, of course – racking up piles of dazzling arpeggios and hurricane wah pedal solos as part of the Volta, the reformed post-hardcore act At the Drive-In and his numerous, genre-spanning side and solo projects. There’s an intriguing disconnect between his perception and the public’s: he’s an icon in front of an amp, like it or not.

But while Rodríguez-López sells himself short as a technician, it’s fitting that he feels out of place next to virtuosos like Van Halen or traditionalists like King. He’s always been a composer who just happened to pick up an axe; he wields guitars like paintbrushes – practical tools for flinging color on a canvas. (It’s telling that his first signature guitar, the Ibanez ORM-1, was about as un-fussy as you can get: one pickup, one knob.)

On the Mars Volta’s early records, Rodríguez-López used effects (delays, phasers, choruses and virtually everything else) as rocket fuel to visit strange new worlds.

“I mean, how old is the guitar?” he mused to Guitar World in 2012. “And there are only 12 notes you can play on it! When you think of it that way, it’s like, in terms of the guitar as a device, what else does technology offer? So you go into the gear, the pedals, the plugins and anything else that has been invented.”

Volta’s relentlessly experimental songs, crafted with singer/lyricist/creative partner Cedric Bixler-Zavala, continue the lineage of edgy guitar tinkerers like Frank Zappa and Robert Fripp – but the band has never lapsed into nostalgia.

Instead, De-Loused in the Comatorium (2003) and Frances the Mute (2005) were genuinely new and vibrant in a way prog hadn’t been since the era of Peter Gabriel’s fox costume – pairing punk energy with Latin groove, metallic ferociousness and jazz-fusion chops.

They needed world-class players to pull it off – original drummer Jon Theodore, who plays with the legitimate bombast of John Bonham, left an intimidating pedal-print during his tenure of one EP and three albums. But it’s no coincidence that the Volta’s most transcendent moments happen to spotlight the guitar.

And as the playing style evolves, so does the band’s music, from the frantic, overstuffed spectacle of 2008’s The Bedlam in Goliath through the more minimalist path of their latest LP, the 2022 art-pop switch-up The Mars Volta (a completely acoustic version of which, titled Que Dios Te Maldiga Mi Corazon, was released earlier this year).

While Rodríguez-López probably wouldn’t approve of us spilling so many words, the breadth of his guitar work deserves the regality of an old-fashioned top 10 list.

10. The Requisition (from 2022's The Mars Volta)

The Mars Volta’s self-titled LP may frustrate fans who crave nothing but gargantuan phaser solos and tricky time signatures; it’s slicker and more hook-oriented than any of their previous six albums, with Rodríguez-López exercising admirable restraint in his quest for reinvention.

But you’ll still find plenty of choice riffs on this self-described “pop” project – they’re just more subtle, typically supporting the vocals and blending into the bigger sonic tapestry. The most obvious “guitar song” here is pseudo-epic closer, The Requisition, one of only two tracks to run past the four-minute mark.

Rodríguez-López keeps his parts pared down for the verses, picking a clean two-chord pattern with occasional sun-ray overdubs. But the vibe turns more sinister from there; the processed drums lift us into a more traditional rock setting, and the guitars snarl and spasm with distortion and wah.

The dissonances and spindly fills even flirt with the menace he utilized so brilliantly throughout De-Loused in the Comatorium – but in keeping with The Mars Volta’s broader aesthetic, the context feels fresh.

It’s possible that some jaded diehards might not give The Requisition a fair shake. Their loss! “Losing ‘fans’ is baked into what we do,” Rodríguez-López told The Guardian in 2022. “I don’t know a greater happiness than losing ‘fans.’ A true fan is someone interested in what’s happening now, and then there’s everyone else trying to control what you do or project onto it.”

9. Cavalettas (from 2008’s The Bedlam in Goliath)

“There are a lot of things I see going on in the world and lots of things I read about that make me very angry,” Rodríguez-López told Guitar Player in 2012. “I try to channel that anger into creative energy rather than pound my fist against the wall or another human being’s head.”

Nonetheless, some of the Mars Volta’s most impactful music – particularly the heaviest moments of their fourth LP, The Bedlam in Goliath – is downright violent, approximating the force of being blindsided in the jaw with a nail-covered 2-by-4. The appropriately titled Bedlam is the apex of the band’s naked aggression and sonic mayhem, piled to the brim with limb-flailing drum fills, harsh vocal effects and ungodly guitar noise.

At its most bombastic, like Cavalettas, it’s all a savory headache, teetering on the border of nervous agitation and sugar-rush excitement. It’s… a lot. The song’s opening seconds offer a roadmap: a shrieking guitar fades in from nothingness, leading to a jolt of superhuman snare rolls and distorted prog convulsions.

Here Rodriguez-López is part of a brutal prog orchestra ducking out occasionally to make room for a scurrying fusion saxophone lick or brooding piano chords

Bixler-Zavala sprays out Dali-like surrealism over the din (“Primordial cymatics giving birth into reverse / Serrated mare ephemera undo her mother’s curse”), now several tracks deep into a lyrical concept that may or may not involve a cursed ouija board.

Here Rodriguez-López is part of a brutal prog orchestra ducking out occasionally to make room for a scurrying fusion saxophone lick or brooding piano chords. But when he takes the spotlight, he isn’t shy – just dig into those chunky funk-punk chords that first swoop in around 1:29 or the creepy-crawly, Zappa-tinted solo around the four-minute mark.

8. Take the Veil Cerpin Taxt (from 2003’s De-Loused in the Comatorium)

De-Loused in the Comatorium is such a dense, hallucinatory concept album, you need two essential tools to follow along: a thesaurus and a copy of the companion book, which fills in some narrative gaps. (It’s impossible to explain the story in a quick blurb, but let’s just say it involves suicide, comas and a bewildering dreamworld that makes Genesis’ The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway feel childlike in comparison.)

An eruption of molten lava after the tranquil ocean waves of acoustic ballad Televators, closer Take the Veil Cerpin Taxt cranks the intensity to a 20 out of 10, both lyrically and sonically. Like many of the album’s heaviest bits, the main riff here is like At the Drive-In meets Red-era King Crimson: rabid and snarling, but with a harmonic richness that raises an eyebrow and leaves you a bit disoriented, like you’re roaming around the Comatorium yourself. (Around the 3:40 mark is a bizarre, liquid-like run that segues into a satisfyingly scrambled squelch.)

It’s a giddy rush trying to process all of these shifts in timbre and tone, and the noise hits harder when balanced out with groove.

It’s a giddy rush trying to process all of these shifts in timbre and tone, and the noise hits harder when balanced out with groove.

About five minutes deep, Flea (on loan here from future Mars Volta tour mates the Red Hot Chili Peppers) digs into a ridiculously funky bass riff – one punctured with icicle sharpness by Rodríguez-López’s guitar.

Then, by song’s end, the engine is revved back up once more: The final 30 seconds find Bixler-Zavala channeling musical theater levels of drama over a pile-driving rhythm, asking repeatedly, “Who brought me here?” over six-string shrapnel.

7. Cicatriz ESP (from 2003’s De-Loused in the Comatorium)

The opening and climactic riff is disarming, alternating between bruising two-note groupings over a hypnotic drum pattern. These sections reach a sort of classic rock clarity: (relatively) minimal effects, pared-back arrangement, 4/4 instead of a difficult-to-count time signature.

But elsewhere, Cicatriz ESP breaks loose from the restraints and goes gloriously full prog. Around four minutes deep, the vibe shifts toward the atmospheric, with Rodríguez-López and John Frusciante (also on loan from the Chili Peppers) trading acid-friendly runs.

It’s a joy to hear the bandleader play with such an enormous canvas, channeling the more expansive jams Volta have so often chased onstage. (“For all the time I spend with the architecture of the music, the guitar solo is just complete expression,” Rodríguez-López told Guitar World in 2006. “It’s the closest I can get to a self-portrait, or a portrait of where I was at the time.”) By the time the 12-minute song reaches its Latin-flavored climax, we’ve reached pure guitar euphoria.

6. Goliath (from 2008’s The Bedlam in Goliath)

The Mars Volta rarely swagger in the traditional sense. But when they do, their swaggering shakes the sidewalks: Goliath might be the closest thing to horns-up hard rock in their catalog, even if the bluesy main lick is unfurled in a tricky 17/4 time signature and the groove shifts into a gentle Latin feel halfway through.

This seven-minute behemoth is an obvious centerpiece of the band’s wild fourth LP, The Bedlam in Goliath, maneuvering seamlessly through several dynamic shifts. It feels lived-in, and for good reason: Rodríguez-López first recorded a slower, funkier version for his 2007 solo record Se Dice Bisonte, No Búfalo. (Most of the Mars Volta’s then-lineup appear on that earlier cut, including Bixler-Zavala, saxophonist Adrián Terrazas-González, percussionist Marcel Rodríguez-López and bassist Juan Alderete.)

It’s only appropriate that the revamped, riff-loaded Goliath, a crucial track within their cursed-ouija concept, is roughly 900 times more volcanic. It’s also fitting that they were pressured into chopping up the song up for radio promotion, even if Bixler-Zavala was pissed about it.

“[T]he end of [‘Goliath’] is so interesting, we didn’t really want it to be used as a single,” the singer told MTV. “It kept getting butchered and came off really bad. If you edit our songs and you take away all the extra stuff, then that song might’ve just sounded like Wolfmother – and we never want to compete with that. They’re their own thing, and we’re our own thing.”

5. Cassandra Gemini (from 2005’s Frances the Mute)

Within the context of 2000s rock music, the Mars Volta’s mind-melting debut was like a transmission from an alien planet. But De-Loused – produced by Rick Rubin, an industry legend who’s rarely ventured into prog, before or since – was almost earthy compared to the glorious indulgence of their 2005 follow-up, Frances the Mute.

The record’s first half has glimpses of relative accessibility, including the eternal power-ballad The Widow. But Rodríguez-López pushed the band into another realm of cinematic splendor with Cassandra Gemini, a 32-minute epic more exhaustive – and exhausting – than anything else in the prog canon.

There are too many riffs to count, as the maestro veers giddily from distorted, paint-peeling bends to squealing wah to palm-muted blues variations to spindly melodies to impressionistic effects that somehow sound like solar flares and laser beams.

But not one second of this insanity feels wasted, or even showoff-y – the guitars are always weaved into an ensemble framework. (Alderete and Theodore add the muscle; keyboardist Ikey Owens brings his own graceful fireworks on various keyboards; a full-blown orchestra makes a memorable cameo; and there’s enough space for Terrazas-González on his silky jazz flute and sax shredding.) It’s a masterpiece.

4. Viscera Eyes (from 2006’s Amputechture)

It’s rare for two famous musicians to mesh without clashing egos or industry meddling, but Rodríguez-López developed a beautifully organic bond with Frusciante. The duo first met in the early 2000s – the Volta leader didn’t even know his new friend was famous – and started playing together casually.

And that chemistry eventually carried over into the recording studio: Frusciante first cranked out some guitar and synth on Cicatriz ESP, then added a pair of scorching solos to Frances the Mute’s L’Via L’Viaquez, but he took on a more substantive role on 2006’s Amputechture, tracking the bulk of guitar parts so the latter could focus on being an objective producer.

“He came in and was literally the guitar player for the album,” Rodríguez-López told Guitar World. “I’m just playing all the guitar solos and parts that needed to be doubled. He said he had fun just coming in, playing his parts and being part of an eight-piece band without having to take on all the songwriting and producing roles that he has with the Chili Peppers. John’s a true guitar player. He makes it look so simple. I just spend most of my time wrestling with it.”

It’s fun listening to a song like Viscera Eyes, the most accessible moment on Mars Volta’s third LP, and pondering the pair’s six-string partnership – during the solo section, with an overdriven lead line splayed out over meaty power chords, we’re probably hearing them both at once.

They achieve some tasty tones at various places: With the guitars meshed into the fabric of Terrazas-González’s soaring saxophone and Owens’ keys, it all hits like one staggering block of sound.

3. Eriatarka (from 2003’s De-Loused in the Comatorium)

Aggressive triplet chords kick off De-Loused’s emotional anchor, and they appear throughout in the choruses, paired with some of Theodore’s most intricate, bombastic drumming.

The Mars Volta never truly shed their flair for post-hardcore, but when it taps that vein, Eriatarka sounds like a progged-out cousin of At the Drive-In’s final LP, Relationship of Command.

Few guitarists can navigate this primal terrain with such color and charisma, but the grand-slams of this song arrive in the softer spaces: on the verses, Rodríguez-López voyages into the psychedelic, layering on blissful effects and exploring seemingly every permutation of his delicate riff through hammer-ons and rhythmic variations.

The most surprising moment is the brief shift into echoing dub at 4:04 – he just couldn’t resist! (It’s worth noting that, prior to forming the Mars Volta, four of the band’s then-members – Rodríguez-López, Bixler-Zavala, Owens and effects operator Jeremy Ward – played in a lesser-known dub group named De Facto. Everything comes full-circle.)

2. Tetragrammaton (from 2006’s Amputechture)

Bixler-Zavala left behind long-form concepts – at least briefly – with the Mars Volta’s third LP. But that didn’t stop him from exploring some deranged ideas, like the story of (possible) demonic possession at the core of 16-minute epic Tetragrammaton. (Not that you need a concrete narrative to enjoy the imagery: “Glossolalia coats my skin / Glycerin and turbulence,” he belts on the impossibly high chorus. “Stuffed the voice inside of God / Mirrors to the animals.”)

Even if the frontman is on fire here, this piece also could have worked as an instrumental – it’s dominated start to finish by the hyperactive guitar work (composed by Rodríguez-López, played largely by Frusciante): the dizzying verse arpeggios and chromatic leads, the jagged staccato stabs on the chorus, the late-song surge of wah, the processed goo that stretches out like taffy during the ambient bridge.

By this point in his career, the composer had even started to embrace the guitar instead of fighting against it: “I was feeling more comfortable with it and just wanting to play it as a traditional instrument,” he told Guitar World, “to see if I was capable of doing that. This record probably has the least amount of effects on the guitar of anything I’ve ever recorded. The instrument is actually recognizable as a guitar.”

Mind you, nothing about Tetragrammaton is “traditional,” but we take his point – he never sounded more natural flexing his muscles.

1. Cygnus… Vismund Cygnus (from 2005’s Frances the Mute)

The song opens so quietly, so blanketed in top-end, that, back in 2005, you probably thought FYE sold you a defective copy – or that maybe your six-disc changer was on the fritz. Rodríguez-López strums a ghostly acoustic progression, as Bixler-Zavala croons imagery worthy of an avant-garde thriller film (“The ocean floor is hidden from your viewing lens / A depth perception languished in the night / All my life, I’ve been sewing the wounds / But the seeds sprout a lachrymal cloud”).

And then, a marvel of modern production: just as you’ve blasted the volume to compensate for the softness, the band pummels you at full power, launching into a percussive Latin funk-prog groove led by Rodriguez-López’s palm-muted squeals and ping-ponging overdubs.

Cygnus is defined by these extreme dynamics: At 4:14, after a confetti blast of effects, Alderete and Theodore settle into a deep, reflective groove, with the guitars shifting into all sorts of strange shapes in the foreground.

The tension slowly builds, the tones lurching and short-circuiting, and we build to another plane with Bixler-Zavala back on the mic. Then we drop out and build back, tracing that arc all over again – a perfectly manic symmetry.