How a new book unearthed Francis Ford Coppola's failed utopia

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

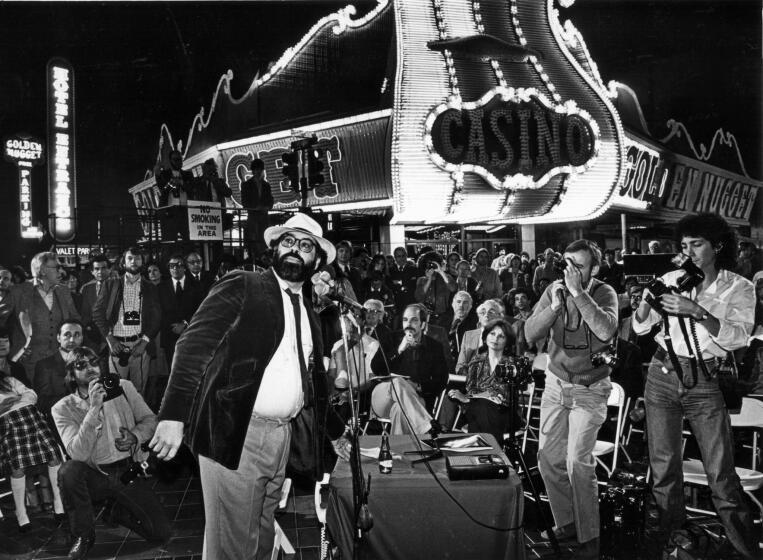

Utopia is in the eye of the beholder. For Sir Thomas More, who coined the word for his 1516 book of the same name, it meant a fictional island society carved out in a satirical image of perfection. For various back-to-nature communities it has meant an embrace of agrarian life and a decision to leave industrial society behind. And for Francis Ford Coppola, the subject of Sam Wasson’s new book, ”The Path to Paradise,” utopia meant changing the rules of how movies are made: multitaskers, freed from the regimentation of studios, constantly reinventing with an eye toward the future.

And for a while, it actually worked. As Wasson writes, Coppola’s career has been “a colossal, lifelong project of experimental self-creation few filmmakers can afford — emotionally, financially — and none but he has undertaken.” As he was churning out his remarkable run of ’70s movies — “The Godfather” (1972), “The Conversation” (1974) and “The Godfather Part II” (1974) — he also was creating a sort of communal filmmaking fantasia, with ideas and technical innovations (and ideas for technical innovations) flowing forth faster than anyone could register (including, at times, Coppola himself).

Read more: Review: Sam Wasson takes a deep dive into 'Chinatown'

He dreamed of what he called an “electronic cinema,” by which a film could be edited as quickly as it was shot, with the director calling the shots from a mobile production facility. He welcomed aspiring filmmakers off the streets of San Francisco and into his American Zoetrope headquarters, a hive of chaos and creativity. It would all come crashing down after his famous flop of a musical, “One From the Heart” (1981). But even this production, undertaken after Coppola created his own Zoetrope studio in Hollywood, is described by many participants as a whirlwind of collaborative excitement, the likes of which can’t be repeated.

In a recent video interview from his Los Angeles home, Wasson, whose previous books include the “Chinatown” study “The Big Goodbye” and, with his mentor Jeanine Basinger, “Hollywood: The Oral History,” recalled how he pitched the project to Coppola: "This is the closest Icarus has come to the sun. No one else has come closer. So rather than frame this as a story about failure, which is how I think Hollywood sees it, let’s position this as a story of success with an asterisk."

Growing up in L.A., Wasson heard stories about Coppola’s grand Zoetrope experiment. “It sounded like a fairy tale,” he says. Indeed, you could find all manner of visitors and participants roaming Zoetrope’s Hollywood shop: Gene Kelly (helping with musical numbers), David Lynch and Jean-Luc Godard (working on personal projects that never came to fruition), Warren Beatty (just there for the parties) and George Burns (whose old office was on the same lot).

Read more: A conversation with Francis Ford Coppola

As Burns’ cigar smoke blended with the aroma of Coppola’s pot, “One From the Heart” production designer Dean Tavoularis and an army of construction workers were hard at work building the movie’s dreamlike Las Vegas sets and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro sat and bathed in his ornate lighting design. Coppola’s young daughter, Sofia, had free run of the lot.

“The Path to Paradise” puts you there, and shows how Coppola got so close to the sun. Growing up in New York, he spent a year in bed with polio, becoming a dreamer. He came out of his shell as a theater student at Hofstra University, studied film at UCLA, befriended a quiet young man named George Lucas (he produced Lucas’ first two films) and grew determined to work outside of what he saw as an inefficient and superficial Hollywood system. He gambled everything making “Apocalypse Now” in the Philippines, and won; then he gambled everything making “One From the Heart” in Hollywood and lost. Deep in debt, he oversaw the dissolution of Zoetrope as he knew it.

He has spent much of his subsequent career as a director for hire, though still capable of gems (“Rumble Fish,” “Bram Stoker’s Dracula”). More recently Coppola threw himself into the modern indie scene he helped create, with “Youth Without Youth” (2007), “Tetro” (2009) and “Twixt” (2011). And still he dreams: He sank a reported $140 million of his own money into the long-gestating “Megalopolis,” an epic about an urban designer played by Adam Driver, now in postproduction following another allegedly chaotic process.

Wasson captures the extreme ups and downs with a combination of precision and imagination, often bringing an appropriately gonzo tone to the story. He imagined the book as a sort of biography of a dream, fueled, as he says, by questions: “How long do we have to sustain utopia before we can call it a success? If it lasts a second, does that mean it's not a success? Francis’ might've only lasted a second, but no one can beat that record. I also wanted to ask: What is a studio now? Paramount is right down the street from me. They make five, 10 s— movies a year, and they sit on all that real estate. They're just banks.”

Read more: Review: 'Priscilla,' Sofia Coppola's best movie in years, shimmers with beauty and heartbreak

The portrait of Coppola painted in “The Path to Paradise” can be ugly; Wasson doesn’t look away from his subject’s warts. He frequently cheated on his wife, Eleanor (whose first-person book about the making of “Apocalypse Now,” “Notes,” and the subsequent documentary, “Hearts of Darkness,” are masterpieces in their own right). He often comes across as the world’s most disorganized boss. And he has endured grief far beyond the movie failures, losing his oldest son and creative confidante, Gio, in a 1986 boating accident.

Wasson credits Coppola for sharing his notes, sitting for countless interviews, reading drafts and insisting the author tell the full story. “It's not always flattering, but it finally is admiring,” Wasson says. “The human errors are all of ours, but none of us, or very few of us, lay claim to this kind of talent or ambition.”

When Wasson recently visited Coppola on the “Megalopolis” set, he found a man at peace. “He would sit there and he would say, ‘There's no rush. There's no rush.’ That's a beautiful thing to see. For all he's given the world and all he's suffered, as a man who built and lost an empire, at 84 he can sit there and be exactly where he wants to be.”

Vognar is a freelance writer based in Houston.

Get the latest book news, events and more in your inbox every Saturday.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.