The Untold Story Of Jean-Luc Godard’s Misunderstood ‘King Lear’: Chuck Norris, A Deal Signed On A Napkin In Cannes & A Director Dressed As “A Rastafarian Christmas Tree”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

There are many stories about Jean-Luc Godard in Cannes, like the year he helped to shut it down (1968) because of the civil unrest that was sweeping France at the time. Then there was the time when (in 1985) he was ambushed in the Palais by a Belgian anarchist and hit in the face with a custard pie after the premiere of Détective. And, as recently as 2018, there was the time he conducted a press conference for his film The Image Book via FaceTime from Switzerland, making journalists line up to speak into a mobile phone.

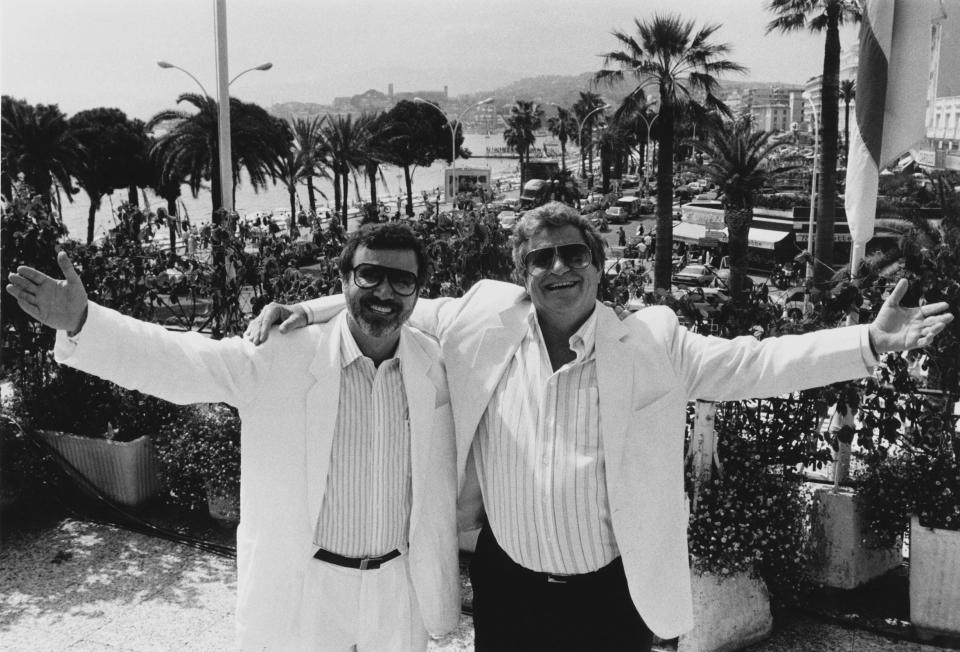

But the story that endures the most is the time in 1985 he signed a contract on a napkin with Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, CEOs of The Cannon Group, whose big hits that year were Invasion U.S.A., starring Chuck Norris, and Death Wish 3, with Charles Bronson. Godard — who died last year at age 92 — was the high priest of art cinema and his work the epitome of avant-garde (The Onion noted his passing with the headline: “Jean-Luc Godard Dies at End Of Life in Uncharacteristically Linear Narrative Choice”). And yet this chalk-and-cheese pairing made a weird kind of sense; Godard had agreed, for $1 million, to make an adaptation of William Shakespeare’s King Lear, written by and starring Norman Mailer, then perhaps the most famous writer in America. Mailer’s daughter Kate would play Cordelia, the headstrong daughter who precipitates the king’s downfall.

More from Deadline

Two years later, a workprint of the film debuted in Cannes to less than stellar reviews, and its backers’ horror was palpable (“He took Cannon for a ride,” fumed Globus). After a screening at Toronto, the film finally appeared as an ultra-limited release in the U.S. in the beginning of 1988. The New York Times described it as “a late Godardian practical joke, sometimes spiteful and mean, sometimes very beautiful, sometimes teetering on the edge of coherence and brilliance, often amateurish and, finally, as sad and embarrassing as the spectacle of a great, dignified man wearing a fishbowl over his head to get a laugh.” For the Washington Post, meanwhile, it was “like finding yourself in the middle of a poem whose meaning the poet refuses to make clear.”

It came and went so quickly that the young Quentin Tarantino faked it on his résumé. “I’d played an Elvis impersonator on one of the episodes of The Golden Girls,” he later told The Independent, “but basically, I didn’t have much of an acting career. I saw King Lear, one of the few people in America who actually did, and I went, ‘Aw, no one’s ever gonna see this movie, I’ll say I was in that.’ It was a really cool credit.” And because there are no actual credits on the film, and perhaps also because it was later noted that it features early acting appearances from French filmmakers Leos Carax (as Lear’s Edgar/ Edgar Allen Poe) and Julie Delpy (as a cinema usher shrieking, “Pall Mall! Marlboro! Lucky Strike! Camel! Phillip Morris!” in heavily accented French), no one twigged. For a really long time.

RELATED: Cannes Film Festival Full Coverage

Despite the irreverent glee that heralded the inauguration of the project, Godard quickly went sour on the project. “I should never have gotten involved in this nonsense,” he told BBC filmmaker Christopher Sykes in 1986. “They tried to con me, Golan and Globus. They think they’re film producers but they’re just clumsy sharks, gangsters who want to be noblemen. Golan tricked me into signing a contract on a paper napkin in a hotel bar at Cannes. I thought it was a joke but an hour later he was holding it up to the press, shouting ‘Godard, Mailer, Shakespeare, King Lear, Cannon!’ People were cheering and I thought, ‘What the hell. I need the money; I’ll do the stupid thing.’”

Almost immediately, there was conflict. Godard claimed that the first four checks from Cannon bounced. Cannon counter-claimed that Godard was over-paying himself, something Godard ascribed to a 30% drop in the dollar-franc exchange rate between 1985 and 1986. And once production did start, it hit another rock. Having arrived in Nyon, a small Swiss town in the Paris-born Godard’s adopted homeland, Mailer and his daughter Kate were dismayed to learn that Godard had become intrigued by a thought that there might be an incestuous subtext to Shakespeare’s tragedy.

Having filmed just one scene, the Mailers left. Godard not only put both takes of it in the film, he broke the fourth wall, recounting in scathing detail how Mailer upped and went in “a ceremony of star behavior.” He later scoffed at the claim that he’d offended the writer. “Just a pretext,” he said. “Mailer loves money. Besides, he wanted Cannon’s backing for his Tough Guys Don’t Dance film. Once he got it he left my movie with $350,000 in his pocket and his movie contract. And there was still no King Lear.”

This is where Peter Sellars comes in. Now an acclaimed director of plays and operas, Sellars was then an actor in his mid-20s. As a freshman he enrolled in a filmmaking class and found himself in a seminar on Godard’s 1962 film Vivre sa vie, starring Anna Karina. “We looked at the film for 15 weeks, frame by frame on a Steinbeck, and accounted for every literary reference, every musical reference, every visual reference,” he says. “It was my first time figuring out what was inside a work of art, and following Jean-Luc’s level of detail was incredible. So I became a worshipper of Jean-Luc.”

This familiarity with Godard’s work proved useful. Mediating between The Cannon Group and Godard in the thankless task of producer was Sellars’ friend and mentor Tom Luddy, co-founder of the Telluride Film festival in 1974, who died earlier this year at 79. “After Mailer left, Jean-Luc had no idea how to continue,” says Sellars, “and Tom knew that the film was stuck. He knew that I loved Godard, he knew that I knew King Lear really well, and so he introduced me to Jean-Luc.”

Sellars met Godard when the director came to New York to film Woody Allen in the Brill building. Allen — playing The Fool but called, in Godard’s narration, The Alien — is sitting at a Steinbeck, splicing film with a needle and thread, reciting a Shakespeare sonnet. Recalls Sellars, “Jean-Luc said to me, ‘Talk to him. Here’s the sonnet. Go teach it to him,’ but Woody said, ‘I don’t know what this is. I can’t say this.’ That scene, which is right at the end of the film, was actually the first thing that was shot in my presence.”

RELATED: Cannes Film Festival 2023 In Photos

It was Sellars who suggested the film’s new Cordelia: Molly Ringwald, fresh, almost literally, from her final John Hughes movie, Pretty in Pink. “I said to him, ‘The person you need in this film is Molly Ringwald. She has everything. She has truly everything. And the movies she’s been in have all been captivating, but she has so much more in her. And if she could actually touch Shakespeare, this would be incredible.’” [Ringwald wrote of her experience for The New Yorker last year.]

In the meantime, to replace Mailer, there were two old-Hollywood options: Rod Steiger, who refused to travel, and Burgess Meredith, who was Luddy’s first choice. “Burgess signed on,” says Sellars, “and then we were all set to go meet Jean-Luc. He insisted that we take the Concord, so the three of us got on the Concord, but when we arrived in Paris, Jean-Luc was still not there.” They spent three days in the airport hotel then went to Nyon, where he was shooting. “Our trips to and from the shoot were silent because Godard was so overwhelming a presence that anything you said sounded unbelievably stupid after he said what he had to say. It was quite intense.”

The work situation was also intense. “At no point did anybody see a script,” Sellars says. “Whatever Jean-Luc wanted to shoot would be presented in the morning to me, and I was to present it to the actors. Two young women were the cinematographers, and they knew that it was an incredible privilege to work with Jean-Luc. They got a serious course because Jean-Luc was meticulous about everything. And I learned a lot of the most important artistic lessons of my life during those days. In particular: never point the camera at the view. Point the camera in some place no one would ever think of looking.”

Molly Ringwald, at 18, and Burgess Meredith, nearly 80, were both old hands by now, actors who were used to serious film sets with such things as hair and makeup. But they found none of the usual niceties in Nyon. “Poor Burgess,” says Sellars, “speaking these lines that he had spoken in his youth, but never knowing what we’re going to shoot from day to day. It was all just literally sprung on him. That’s why, in the film, I have to write things down and hand them to him, like it’s a telegram that’s being delivered, for example, because Burgess never had the time to learn any lines. And he felt that as a humiliation. But, of course, for Godard, it becomes one of the most poignant and beautiful things of the film as you watch human failure with old age. It has a tragic stature that I think Burgess never realized was coming across in the footage.”

Suddenly, after three days of shooting, Godard sent Ringwald and Meredith home. “He said, ‘I’m done. I don’t need to see anything more.’ They were shocked. They thought they were being fired, but he said, ‘I just don’t need to see anything more.’”

What nobody knew was that Godard’s film was starting to come together in his mind, and Mailer’s original vision for the film had planted a seed: that script was called Don Learo, since Mailer thought, as he says in the film, that “the mafia is the only way to do King Lear.” Meredith, as Learo, was a depository for everything Godard hated about the movie industry, and the film is rich with references to the mob and Las Vegas, while alluding to the idea of mainstream cinema as exploitation, a form of racketeering.

The finished film begins with that sense of vitriol: before Godard’s denunciation of Mailer, there are panicked voicemails from Golan and Luddy and a stark intertitle screams, “A PICTURE SHOT IN THE BACK.” (By whom? By Mailer? By Cannon? Or Godard himself? All these readings are possible.) But once this is out of the way, King Lear becomes, very recognizably, of a piece with the work Godard was doing in the same period, films that actively deconstruct storytelling while at the same time expressing sophisticated ideas about art and beauty. In this case, this means cross-pollinating King Lear with Shakespeare’s Sonnets, Virginia Woolf’s The Waves and a whole lot more.

The setting is a post-Chernobyl world where society has rebuilt itself after a harrowing nuclear winter, but art and culture has been destroyed. Into this bleak landscape comes William Shakespeare Jr. the Fifth (Sellars), who is on a mission to restore his ancestor’s works. Along the way he encounters Professor Pluggy (Godard himself), a character memorably described by the Washington Post as “decorated like a kind of Rastafarian Christmas tree with variously colored audio and video patch cords, chomping a cigar and speaking, nearly incomprehensibly, out of the side of his mouth.”

It’s quite a look. Did Sellars know he was going to do that? “No,” he says. “When you see the film, you’re seeing me walk in and see him for the first time looking like that. And then I have to come in and sit with him. But, you know, it makes sense. He considered himself to be on the cutting edge of film technology, the technology of tomorrow, and so his wig is his statement of him not being in the world of John Ford. It’s his way of saying that the future of film is going to be this high-tech, electronic manipulation. So when we meet, he and I are in solidarity, because he, also, is reconstructing a lost art — the lost art of film — but with new technology.”

Sellars got it, but not everybody would, as he found out when the film premiered at Cannes. “We showed the film in the big screening room there,” he says, “which has a particular sound effect: when people decide to leave, those seats flip up and go boom, boom, boom, boom… There was a torrent of that all the way through the film.”

The press conference was similarly memorable. “It was one of the most vituperative press conferences in the history of Cannes,” Sellars says. “It was a room of seething, carnivorous, animal energy. People trying to tear him limb from limb and eat his flesh. The hostility in the room was like, ‘Mr. Godard, how could you possibly insult us with a failure that is even greater than the failures of the last five years? How can you possibly dare to present something so empty? Have you lost all your talent? Have you lost all your integrity?’ And he would proceed to answer every question with a discourse about Mondrian, Rembrandt, Beethoven, Greek tragedy, the entire history of culture. It would go on for 20 minutes. Then he would turn to me and say, ‘Peter?’”

On its release in the U.S., the film found better favor with critics such as Jonathan Rosenbaum, who instinctively understood its many layers of meaning while pointing out its many idiosyncrasies (such as Godard deliberately speaking “semi-coherently out of one side of his mouth,” a bizarre affectation that swamps much of his dialogue). Cannon, however, wanted it gone, and the film has barely been seen since a boutique release in France resulted in a €5,000 copyright claim from French author Viviane Forrester.

In America, it was recently shown in April at a tribute to Luddy, where Sellars was pleased to see their work hold up, despite the tension of opposites at the heart of it.

“For Molly and Burgess, a major film was a big-budget thing with huge personnel, but for Jean-Luc, it was a private-journal entry. King Lear is an essay written in isolation, reflective of the world but also about himself. And you get all of that inside this splintered, violent film, which is deliberately self-destructive in the way that King Lear himself was self-destructive. Like Lear, Godard’s main enemy is himself, but at the same time he’s bitter about all his enemies, so you get the gangster motif, and the connecting of Las Vegas to Hollywood, the idea that the commercial cinema is a giant come-on to make a lot of money that actually leaves people empty and broke emotionally.

“He’s on point over and over again in his super-brilliant aphoristic manner. And it adds up astonishingly, because by the end — even though you can’t follow it or, if you can, you’re not aware of it — it has an accumulative power that is truly incredible.”

All of this alchemy happened in the course of less than two weeks.

“Jean-Luc was one of a kind,” Sellars says. “There will never be another. No one can match those films. They’re in their own category, and you know you’re with a master. You can see from 50 paces that it’s a Picasso painting that you’re approaching, and it’s the same with Godard. He created a language, a signature, and a handwriting that is totally, unmistakably his.”

Best of Deadline

Cannes Film Festival Photos Day 2: Johnny Depp, Pedro Almodovar, ‘Anselm’ & More

2023 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.