The unspeakable tragedy at the heart of Paul Auster’s work

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“The writer and detective are interchangeable,” says the novelist Daniel Quinn in Paul Auster’s City of Glass, the 1985 novella that would form part of his break through 1987 work The New York Trilogy. That tricksy riddling novella, full of shapeshifting shadows and narrative dead ends, established Auster as a writer of hall of mirrors meta fiction in a literary landscape otherwise dominated by gritty realism.

Featuring a character called Paul Auster, who, like Auster at the time in real life, also has a wife called Siri and a son called Daniel, it’s both a playful recalibration of the detective fiction genre, in which Quinn is hired to prevent a former convict from murdering his son, and a mysterious exploration of the collapsable borders between fiction and real life.

“The detective is the one who looks, who listens,” says Quinn, himself a detective fiction writer. “[He] moves through this morass of objects and events in search of the thought, the idea that will pull all these things together and make sense of them.” He might have been describing the relationship between Auster’s own life and his work.

When Auster died yesterday in Brooklyn at the age of 77, following a two year battle with lung cancer, he left behind one of the strangest and most idiosyncratic bodies of work in American literature. The New York Trilogy might have been never bettered by anything that followed, yet nearly all Auster’s singular writing shares the same preoccupation with the protean nature of identity, with the often anguished relationship between fathers and sons, with grief and loss, and with the ambiguous interplay between truth and narrative reconstruction.

No one could ever accuse Auster of writing autobiographically – his novels are far too mischievous, evasive and postmodern for that. All the same, several, like City of Glass, contain an explicit self referential tease: the Booker shortlisted 4321 offers four possible life stories of a man named Paul Auster; Auster’s elegiac final novel Baumgartner, published last year, features a potted version of the elderly protagonist refers to as the Auster family tree.

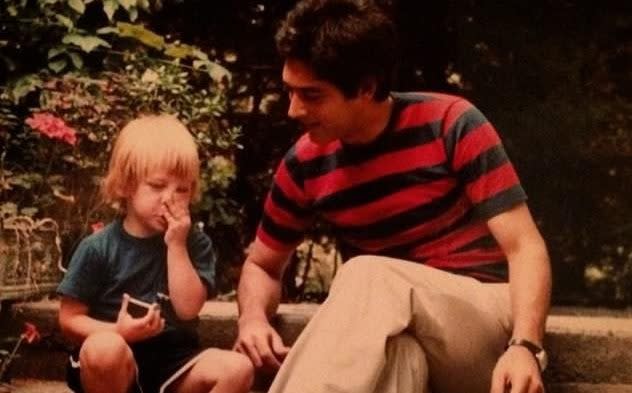

Yet the most poignant real life spectre to haunt Auster’s work, flitting intermittently in and out of the background like a moth in the twilight, is that of his son, Daniel, who was born in 1977. In 2022 Daniel was found dead in a New York subway station from a drug overdose.

Just four hours previously he had been released on bail after being accused of manslaughter over the death of his 10 month old daughter Ruby, who had died in 2021 from acute intoxication of heroin and fentanyl. It was never established how she had ingested them but Daniel, who had taken heroin on the day of her death and woke up a couple of hours later next to her lifeless body, later admitted he kept his drugs in the bathroom.

Auster first wrote about Daniel in his 1982 memoir of his own father, The Invention of Solitude. He describes him with palpable affection as an 18 month old “putting lampshades on his head” and “running through the vast spaces of the gradually emptying rooms” while Auster and his then wife and Daniel’s mother, the writer Lydia Davis, sort through Auster’s recently deceased father’s possessions. Later he recalls Daniel’s “sweet and ferocious little body as he lies upstairs in his crib asleep”.

Yet in the second part of the book, he also makes clear how much, as a father, he is haunted by the image of dead children. He writes about Etan Patz, a six year old boy who went missing on his way to school in Manhattan in 1979 and was never found; and about the 19th century French poet Mallarme, whose only son died at the age of eight. And he writes about the time Daniel, aged two, almost died from a respiratory illness and would have had Auster and Davis not taken him to a hospital in time.

Quinn, too, in City of Glass, used to be obsessed with stories about dead and damaged children, once pouring over them fanatically as one can imagine Auster might have done. What’s more, Quinn has also lost a young son. “He thought of the little coffin that held his son’s body and how it had seen it on the day of the funeral being lowered into the ground,” writes Auster. “That was isolation, he said to himself. That was silence.”

Long before he died, Daniel’s life had been marked by tragedy and horror. In 1995 he was present in a Hells Kitchen apartment when the drug dealer and club scene leader Andre Melendez was savagely killed by Daniel’s friend and party promoter Michael Alig and Alig’s close friend Robert Riggs. All four were prominent members of Manhattan’s then underground club scene in which copious quantities of glitter, platform heels and ecstasy were de rigueur accessories.

Alig, though, had become addicted to heroin and, after falling in debt to Melendez, he and Riggs bludgeoned Melendez with a hammer, poured drain cleaner down his throat, sealed his mouth with duct tape, cut up his body and dumped him in the Hudson river. Daniel, who was himself passed out on heroin at the time, was never implicated by a court in the murder, although in one of the eerie threads that weave throughout Auster’s life and oeuvre, he was known in the club scene for carrying a copy of American Psycho – Bret Easton Ellis’s landmark 1984 novel about a wealthy banker consumed by murderous fantasies. As one friend put it: “It became this joke that Paul Auster had a kid from The Omen on his hands.”

In 1998 he pleaded guilty to possession of $3,000 of stolen money, widely believed to have been stolen from Melendez by Alig on the night of the murder and given to Daniel as hush money.

The Melendez murder rapidly acquired its own mythology in popular culture, poured over by true crime fanatics and became the subject of the 2014 film Party Monster, starring Chloe Sevigny and Macaulay Culkin.

Yet one is also tempted to think that, in all its awful decaying glamour, the crime was queasily in keeping with Auster’s own aesthetic flirtation with a sort of grubby baroque sensationalism. Lurid tragedy features heavily in his work – the lead character of 2002’s The Book of Incident loses his wife and child in a plane accident; in 4321 a boy is killed by lightening. The critic James Wood even said, not entirely approvingly, that there was something of the B movie about his novels.

What’s more Auster’s own family history contains its fair share of garish incident. In 1919 his grandmother killed her estranged husband in the kitchen of their Wisconsin home, apparently following an argument over money and his friendship with another woman. The case caused a sensation, although Auster’s grandmother was later acquitted on the grounds of insanity.

Yet the case plagued Auster, who obsessively read every newspaper report about it published at the time. “[The articles about the murder] loom up at me with all the force of a trick of the unconscious, distorting reality the way dreams do,” he writes in The Invention of Solitude.

Auster almost never spoke publicly about Daniel, but a protagonist in his 2003 novel Oracle Night, John Trause (Trause being an anagram of Auster) is a writer whose son is a violent drug addict for a son. In 2003 his second wife Siri Hudsvedt, whom he married in 1982, published the highly acclaimed novel What I Loved, set in the New York art world and whose cast includes Violet, whose step son Mark becomes involved with an artist who commits a gruesome murder that bears barely veiled similarities to the Melendez case. “Did we cause it?” asks Violet, on the subject of Mark’s unstable personality. “Did we ruin him? I don’t know…”

Auster would never permit him self such direct questioning in his art. Instead his novels - restless, opaque, sometimes tragic – might be seen as a sort of dreamland manifestation of the existential questions that tormented of his subconscious. In his memoir he describes reading Pinocchio to Daniel when he was young.

“For the little boy to see Pinocchio, that same foolish puppet who has stumbled his way from one misfortune to the next, who has wanted to be ‘good’ and could not help being ‘bad,’ for this same incompetent little marionette, who is not even a real boy, to become a figure of redemption, the very being who saves his father from the grip of death, is a sublime moment of revelation.”

Storytelling, of course, often provides a redemption that real life cannot.