The Unseen Freddie Mercury: Exploring the Private Man Behind the Bohemian Rhapsody Character

The man who would become Freddie Mercury seemed depressed as he sat in a London pub one day in the late ’60s. “I’m not going to be a pop star,” he sighed glumly, as classmate Chris Smith would later recall. Then a smile spread across his face as he rose to his feet and threw his arms out in a heroic pose that would become familiar to millions of fans: “I’m going to be a legend!” It was a laughable notion for an unknown art student barely into his 20s. But then it happened.

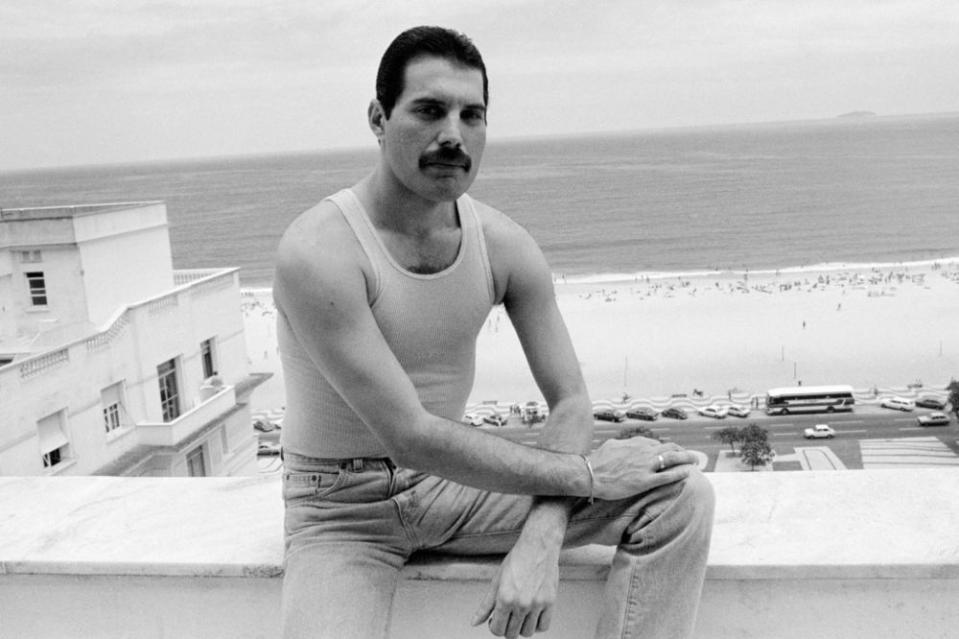

As the frontman of Queen, Mercury became a bonafide rock superhero. His powerful baritone could leap tall octaves in a single bound, providing operatic grandeur to hits like “We Are the Champions,” “Somebody to Love,” and the epic “Bohemian Rhapsody.” In concert, he could enthrall thousands with a mix of strength, seduction, and regal glamour.

Today, 27 years after Mercury died of complications of AIDS at age 45, his allure can still draw a crowd. Bohemian Rhapsody, the blockbuster film starring Rami Malek in his Oscar-winning role as the late singer, is the highest-grossing biopic in history, thrilling old fans and introducing new generations to the band’s unforgettable music. “Queen are even bigger than when they originally put the records out, and Freddie would love it,” BBC broadcaster Paul Gambaccini, a longtime friend, tells PEOPLE. “He would just flip his hand and say, ‘It’s fabulous, darling!’”

Mercury was born Farrokh Bulsara on Sept. 5, 1946, the son of a court cashier and a homemaker in Zanzibar, a British protectorate off the African coast. While his family, Persian-descended Parsees, practiced the ancient Zoroastrian faith, young Farrokh was a devout follower of Western culture, devouring pop records and fashion magazines, which often took months to arrive on their remote shores. Mercury characterized himself as “a precocious child,” and at the age of 8 he was sent to a boarding school across the ocean in India. “It was an upheaval of an upbringing,” he later admitted. It was there that he formed his first band, the Hectics, and adopted the name “Freddie.” According to Lesley-Ann Jones, author of Freddie Mercury: The Definitive Biography, another lifelong trait took root at school. “Freddie had this yearning void which was primarily to do with the fact that his parents sent him thousands of miles away.”

He briefly returned to Zanzibar before violent revolution broke out in 1964 and the family migrated to the London suburb of Fulham. Mercury wasted no time throwing himself into the Swinging Sixties scene, enrolling at art college alongside future Rolling Stone Ronnie Wood, and plastering his room with pictures of his hero, Jimi Hendrix. He sang with several local bands, but he had his eye on a trio called Smile, which included guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor. With trademark enthusiasm, he offered a long list of unsolicited suggestions to the group, even shouting, “If I was your singer, I’d show you how it was done!” in the middle of their shows.

When their vocalist ultimately quit in 1970, he got his chance. With the addition of bassist John Deacon the following year, they dubbed themselves Queen. The unusual name, twisting notions of class and sexuality, was Mercury’s idea — naturally. “The whole point was to be pompous and provocative, to prompt speculation and controversy,” he told PEOPLE in 1977. In the same spirit, he gave himself a new surname. Forevermore he would be known as Freddie Mercury.

For his stage persona, he drew elements from rock heroes like Hendrix as well as more unorthodox sources which recalled an earlier show business era. “Liza Minnelli was one of Freddie’s great influences,” Gambaccini observed. “Because Freddie was usually not playing an instrument, he learned from her the use of the hands. He’s taking elements of stage direction from Bob Fosse via Liza Minnelli, and thus those larger than life gestures.”

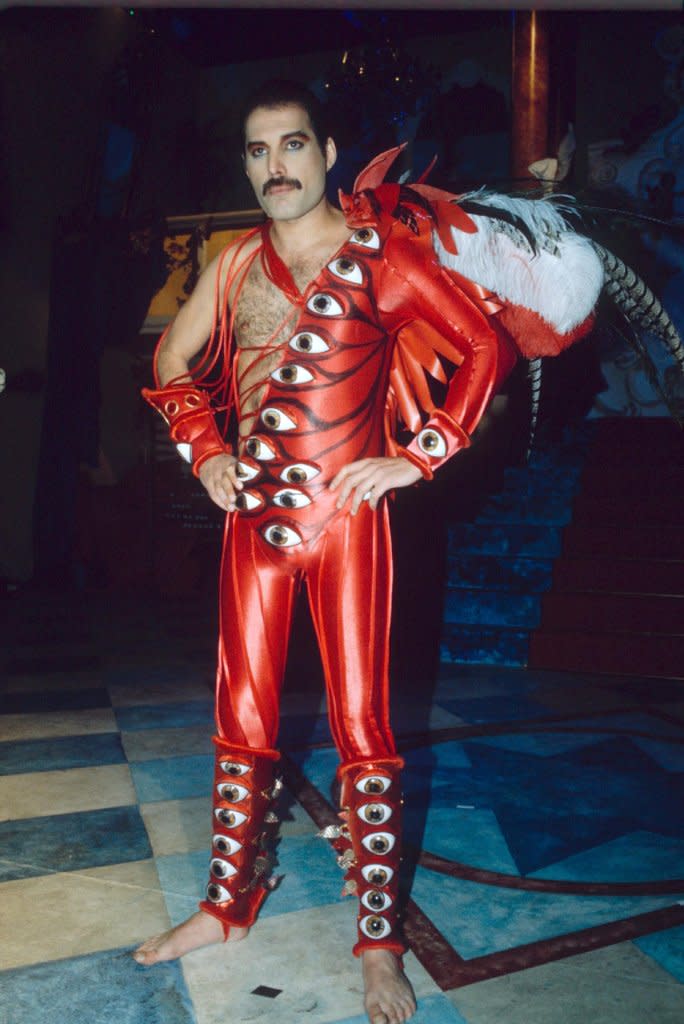

His fashion choices were equally dramatic, bending the conventional views of gender. “I think Freddie was one of the early exponents of the androgynous movement — like David Bowie,” says designer Zandra Rhodes, who created some of his best-known costumes during Queen’s early period. “I think he’d seen my chiffons with feathers and exotic sleeves and extreme approach to fashion,” she tells PEOPLE. Her most famous look for Mercury, a flowing white silk “batwing” cape shirt, had its genesis as, of all things, a wedding dress. “He and Brian came to my tiny Bayswater attic studio, incognito. I asked Freddie to look along my rail of clothes and he chose an exotic pleated bridal top I had on the rail! He danced around in it in my studio.”

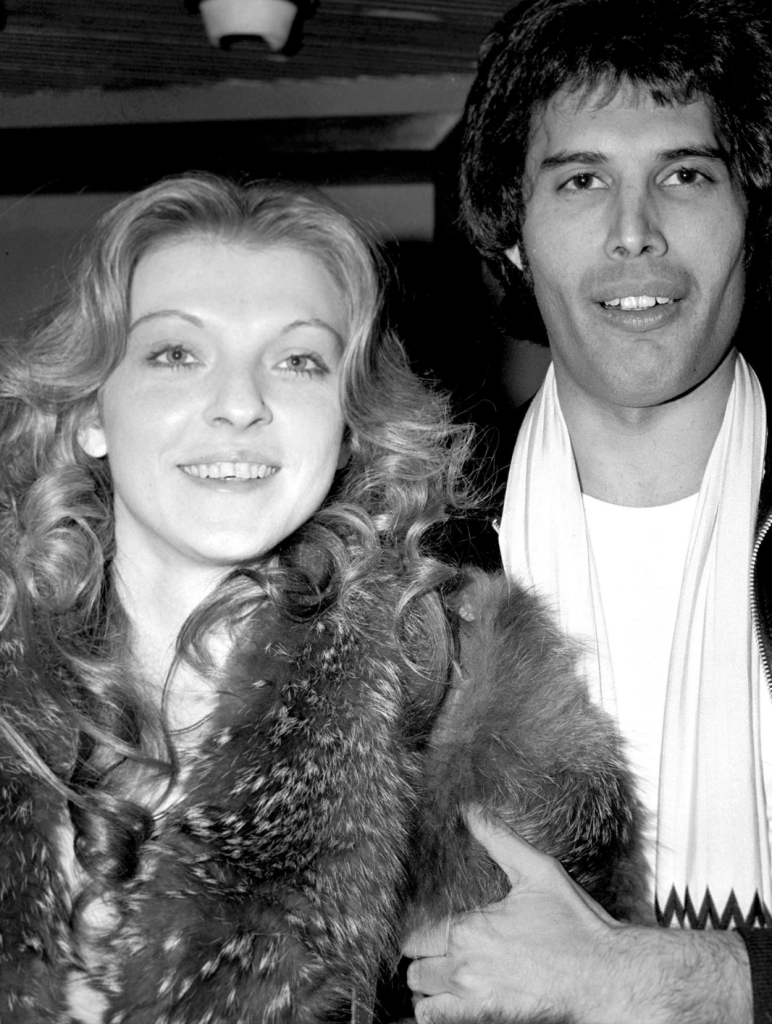

As the band’s career took off with the success of “Killer Queen” in 1974, his personal life began to shift. Since 1969 he enjoyed a warm romantic relationship with Mary Austin, a glamorous 19-year-old who worked at London’s chic Biba fashion boutique. The pair shared an apartment and were even engaged to be married, but Austin noticed something wasn’t right between them. “I knew that this man wasn’t at one with himself over something,” she says in Rudi Dolezal’s Grammy-nominated 2000 documentary Freddie Mercury: The Untold Story. As Gambaccini reflects, “I think Freddie was one of those people who was surprised to find out, as a young adult, that his gay impulses were stronger than his heterosexual impulses.”

Eventually, Mercury confessed his feelings to Austin. “I felt like a huge burden had been lifted,” she recalled. “Once that had been discussed, he was like the person I’d known in the early years.” Though their romance was over in the traditional sense, they would remain close for the rest of his life. “All my lovers asked me why they couldn’t replace Mary, but it’s simply impossible,” Mercury said in 1985. “The only friend I’ve got is Mary, and I don’t want anybody else. To me, it was a marriage. We believe in each other, that’s enough for me.”

Many close to Mercury, and many fans, believe that his feelings of guilt for Austin, coupled with the relief of embracing his own sexuality, inspired “Bohemian Rhapsody,” his greatest musical masterpiece. The opening line “Mama, just killed a man” has a mournful quality, as if he’s saying goodbye to a part of himself. “That was obviously alluding to Freddie killing off the old Freddie and becoming the new Freddie that he needed to be,” says Jones. Peter Hince, Queen’s roadie throughout the band’s live career and author of Unseen Queen, agrees. “It’s a very, very personal statement,” he tells PEOPLE. “Over the years I’d say to Fred, ‘What’s it about?’ ‘Oh, well, it’s about this and that. Bit of this and that.’ Right, okay…” Mercury was equally vague in interviews. “I’ll say no more than what any decent poet would tell you if you dared ask him to analyze his work,” he once said. “If you see it, Dear, then it’s there.”

Regardless of its true origins, the six-minute juggernaut defied industry expectations and became an international smash at the end of 1975, establishing Queen as top rock headliners. No expense was spared as the band hit the road the following year. “Fred was like, ‘No, we’ll have the biggest, we’ll have the best.’ Doesn’t care what it costs. ‘I want it. And if we’ve got one, we’ll get a spare one!’” says Hince. For the frontman, it all came down to his personal motto: “Quality and style, Dear!”

Filmmaker Rudi Dolezal, who became close to Mercury after directing dozens of Queen-related music videos, remembers a conversation they shared one night after a party at the singer’s home. “Freddie said, ‘I do this because I want to know if I’m still number one when I’m behind the microphone. That’s the kick. It’s successful because I proved it to myself.’” But the excellence came with a high cost. “He told me, ‘For each step that you go up the ladder of success, you have to leave something behind that you love,’” recalls Dolezal. “’You will lose friends, you will maybe even lose family, that’s the price you have to pay.’”

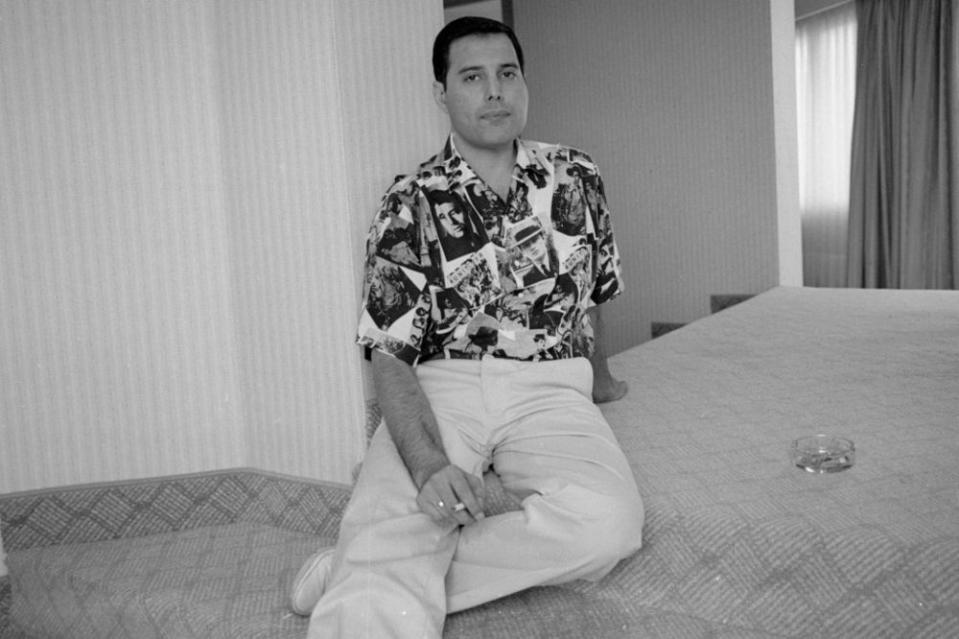

Despite his inexhaustible energy and charisma as a showman, to his friends he was just regular Fred. “Freddie was very extrovert onstage, as we all know, but he was very shy in his private life and liked to be private,” Brian May told PEOPLE in 2017. “He liked those moments of just having a couple of his close friends around. We’d known each other a long time and we were almost like family. We had no airs and graces with each other.”

Even his songs could come from charmingly humble beginnings. Peter Hince was nearby when Mercury started writing the first few bars of “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” — in the tub. “He was in the bath and you could hear him humming and stuff. He came out and said, ‘Give me a guitar, give me a guitar.’ I got an old acoustic and he just started banging out the chords on it. Then he said, “Right, call the studio!’”

In 1979 Queen decamped to Munich, Germany, to work with producer Reinhold Mack, who would collaborate with the band for five albums, starting with 1980’s The Game. Freddie would enjoy an especially close relationship with Mack and agreed to be godfather to his son — called Freddie, in his honor. When the child was born, the elder Fred sent a special gift to Mack and his wife, Ingrid. “Freddie wanted to send some flowers and his aide called from the florist and said, ‘What should I get?’” Mack remembers. “Freddie said, ‘For f—’s sake, just buy the entire store!’”

Mercury would share a bond all three of Mack’s children for the rest of his life, leaving them notes reading “Just go for it — my love is with you always,” and other handwritten messages. “He would swim in the pool and play table tennis with the kids,” says Mack. “Many times they went shopping with him.” Often they had movie nights with the Macks and Freddie curled up on the couch with hot cocoa. “The nicest thing was when he said, ‘Oh, this was actually like in a real family.’”

Once, Mercury asked Mack’s older son Julian what he wanted for his birthday. “Julian said to him, ‘All I want is for you to show up to my party in the costume from the ‘It’s a Hard Life’ video.’ And he did! Well, he didn’t come to the door in the costume. I heard him changing in my bedroom saying, ‘I can do this on stage. I can do this at this party…’”

Of course, Mercury wasn’t only going to kids’ birthdays. “Freddie knew how to party,” Dolezal says with a mischievous laugh, adding that many of Queen’s music video shoots ended up with a raucous gatherings at Mercury’s house. But it was while out on the town one night that he first approached a ruggedly handsome Irish hairdresser named Jim Hutton with an unorthodox pick-up line. “He asked me how big my c— was. It was simple as that,” Hutton recalled in a 2002 television documentary. “And I think my reply was ‘Well if you want to know you’ll have to find out.’ He was very brash, and if he fancied someone, he made no bones about it.” The pair would remain together until Mercury’s death.

Though it seems strange now, Queen was at a commercial nadir by the mid-‘80s. “People thought Queen’s best moments were behind them,” Paul Gambaccini says. It had been a decade since the highs of “Bohemian Rhapsody,” and five years since their last major hits in the United States. “They were sort of the elder statesman of rock. Queen were not cool,” Lesley-Ann Jones says. “They are cool today, but they weren’t cool back then. You were either a Queen fan or you really weren’t a Queen fan.”

There was even some mild concern within Queen’s own camp about the future of the band. “There’s a real possibility they were going to break up around then, because they’d been doing it for a long time,” Hince reveals. “I think John [Deacon] was pretty tired and he had this big family, and Fred was doing his solo stuff, so I think they were at a low ebb. I didn’t think they’d definitely break up, but it was more like, ‘Well, what are they going to do next?’”

Despite Bohemian Rhapsody‘s portrayal of upheaval within the group, Hince rejects the notion that they were at odds with one another. “Certainly they would argue in the studio, and they would argue over things on tour. But the way it was shown was wrong. It appears that the band fired Freddie, which just never happened.” Dolezal, another one of the privileged few to witness the band recording, claims that Mercury often served as the mediator during heated discussions. “Queen was a democratic band. The four of them were equal. When they had arguments in the studio, when I was present, Freddie was always the one who said, ‘Come on, let’s not fight here.’ He was the peacemaker, and not the one who was the problem by being a diva.”

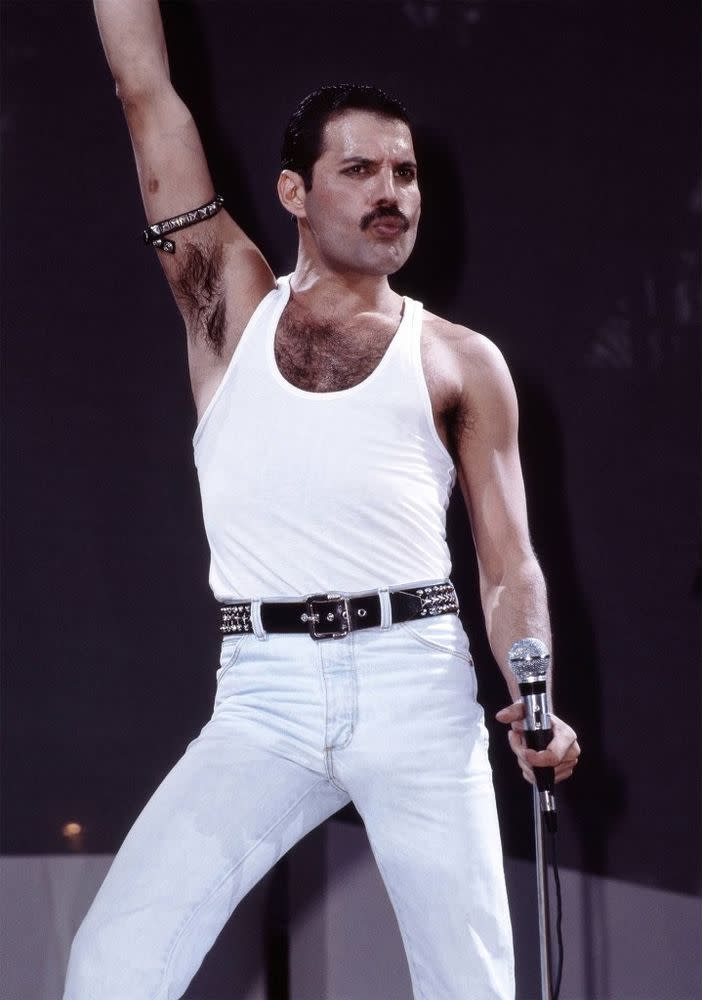

An invitation from Bob Geldof to perform at the historic Live Aid concert for African famine relief proved a much-needed boost for the band. The biggest names in music pledged to appear at England’s Wembley Stadium that hot day in July 1985, including David Bowie, Elton John, U2 and Paul McCartney, which added to the stress of a tightly scheduled satellite broadcast. “There was obviously a lot of tension,” says Hince. “For the first time Queen went on to a stage without a sound check!” But Brian May remained confident. “It wasn’t foreign territory to us,” he explained to PEOPLE. “To most of the people it was very daunting because they hadn’t developed that knack of transmitting the energy to a huge stadium, whereas we went on knowing we could connect.”

At 6:41 p.m. Mercury stepped out in front of 70,000 people — plus the hundreds of millions watching on television — and delivered a 20-minute performance of a lifetime. Their stage presence had been honed to perfection through nearly 15 years of shows, and their truncated setlist was skillfully crafted for maximum impact. “They had whipped their set into time during their rehearsals at the Shaw Theater the week before,” says Gambacinni, who was commentating for the BBC at Live Aid that day. “They took very seriously to heart Bob Geldof’s admonition to all the performers, ‘Do your hits. Don’t promote new songs, and you have to keep to a certain time, because the satellites are booked.’” Catching the set on a monitor in the star-studded backstage area, he knew he was watching something special. “You could feel the frisson amongst the artists,” he says. “Everybody realized that Queen was stealing the show.”

The impact of the performance was immediately obvious even to Brian May. “I don’t think we realized how much we’d evolved, but it was apparent after we came off that stage at Live Aid that we had connected in a way that absolutely fitted the occasion.” The British public — if not the world — made it clear that the band was the audience favorite. “The BBC took a survey of its listeners and viewers the following week asking who was the best at Live Aid,” remembers Gambacinni. “Sixty percent said Queen. Now, when you bear in mind who else was on that bill: Elton, McCartney, Bowie. For more than 50 percent of an audience to agree on anything is amazing. But for 60 percent to say that the world’s greatest were outshone by Queen on the day — that shows you the power of that performance.”

As far as his friends are concerned, Mercury never aimed for anything less. “He strove to be the best, to be the biggest band, to put on the biggest show, and to raise his game,” says Hince. “He had that effect on everyone around him.”

The jubilant Magic Tour would come the following year. “Freddie was as strong and exuberant as he’d ever been,” says Jones, who accompanied the band on the trek. “There was no inkling, no suggestion that things were on a decline.” But Queen’s time at the top would be cut tragically short as AIDS spread with horrific speed through the gay community of New York City and beyond.

“Everybody was in advanced panic. Everyone was trying to figure out, what is this new disease?” remembers Gambaccini. “We were just losing so many, we didn’t even have the time to mourn everybody properly. These people had indulged in unsafe behavior before it was known to be unsafe, and most people thought it pointless at the time to test yourself, because it took two weeks to get the results. Those are the most terrifying two weeks of your life. Also, there were no drugs you could take to help, so you would just know that you were going to die. So most people didn’t get tested until they first developed some kind of symptoms.” Knowing that Mercury frequented many of these New York clubs, he offered a word of caution. “I said, ‘Have you modified your behavior in light of the new disease?’ He said, with a flourish of the arms, ‘Darling, my attitude is f— it. I’m doing everything with everybody.’ I had that sinking feeling because I thought, ‘We’re going to lose Freddie.’”

Mercury was diagnosed with AIDS in 1987, but the news was kept from all but his innermost circle. Primarily he wanted it hidden to respect his parents, to whom Mercury never divulged his sexuality. “He could never come out and be gay or bisexual because their religion does not allow it,” Jones says. “He was very respectful of his parents and he did see them, but they weren’t aware of his private life until after he died. I’m sure that we would’ve found a way dealing with it, but they were from a different generation and the expectations were different. They weren’t uncompassionate people; they were very loving parents, but they were from a different time, from a different country and a different religion.”

RELATED VIDEO: Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ Is the Most-Streamed Song from the 20th Century

Eventually, Mercury revealed his condition to his bandmates one night over dinner. Brian May remembered the occasion in the 2011 documentary Queen: Days of Our Lives. “He did sit us down and say, ‘Look you know what I’m suffering from, you know what the problem is, but I don’t want to talk about it anymore. I just want to make music until the day I f—ing die. And let’s get on with it.’”

Unable to perform, he threw himself into studio work, recording songs he knew would be finished after he was gone. “Sometimes it would only last a couple of hours a day because he would get very tired,” May later said. “But during that couple of hours, boy, would he give a lot. When he couldn’t stand up, he used to prop himself up against a desk and down a vodka: ‘I’ll sing it till I f—ing bleed.’”

Mercury spent his final days with Hutton, Austin and other friends at Garden Lodge, his elegant Neo-Georgian home in the heart of London, looking at art, playing Scrabble or pampering his beloved cats. Movie nights with Mack took on a more somber tone. “We saw Amadeus about eight times, just sitting with him on the couch,” he remembers. “At the end when Mozart gets thrown into a ditch and covered with chalk and he said, ‘Look, this is what’ll happen to me. Just make sure that they don’t f— up my music.’”

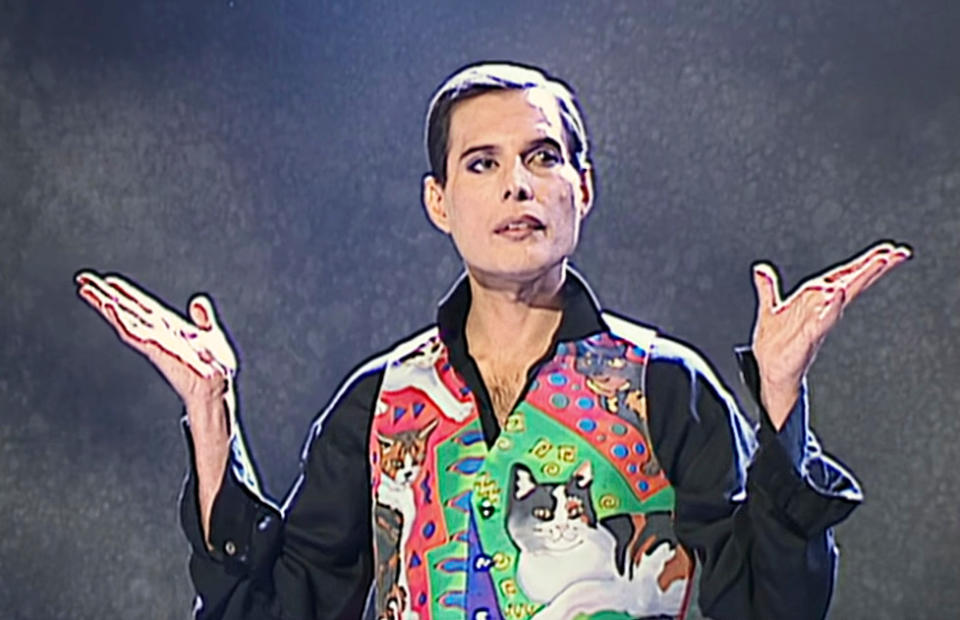

In his last months, Mercury teamed up with Dolezal to film the video for “These Are the Days of Our Lives.” A winsome look at time gone by, the track is one of the last Queen songs released during his lifetime. The director had been warned to keep things speedy because of the performer’s ailing health. “AIDS was never a topic. We never discussed it. He didn’t want to talk about it. Most of the people didn’t even 100 percent know if he had it, apart from the band and a few people in the inner circle,” says Dolezal. “He always said, ‘I don’t want to put any burden on other people by telling them my tragedy.’”

They shot in black and white in a desperate attempt to conceal Mercury’s physical deterioration, but his emaciated frame is painfully apparent. “The bottom of his foot was a completely open wound,” says Dolezal. “He must have had terrible pain, but you don’t see that. You just see a man and his destiny. Regardless [of] whether he was in pain or not, he always delivered. He didn’t want any special treatment. He was so brave. In retrospect, it would have been so easy to be a diva, but he wasn’t like that.”

Just before wrapping the day of the shoot, Mercury requested one more take for the last lyrics of the song: Those days are gone now but one thing’s still true / When I look and I find I still love you. On the last line he summons all his strength for a final heroic pose — just as he had done as a penniless art student in a pub more than 20 years earlier. Then he collapses into himself with a soft laugh. Staring through the camera, he whispers a final, “I still love you,” before snapping his fingers and walking out of frame with a flourish.

“He knew how ill he was and that this was the last time he’d ever be in front of a camera,” says Dolezal. “In these last few seconds of that song, he gives us a resume of his whole life. ‘I was a big superstar, but don’t take it too seriously.’ And then, ‘I still love you,’ which is to the fans, and then he walks out of life. That’s how he wanted it to be.”

Freddie Mercury died at home on Nov. 24, 1991, a day after issuing a public statement confirming his AIDS diagnosis. The international rock community would gather at Wembley Stadium, the site of his greatest triumphs, the following April, to pay tribute with a concert to benefit AIDS research. Brian May would pen what was the simplest epitaph for his friend: Lover of Life, Singer of Songs.

“At least he lived long enough to reach fruition,” reflects Gambaccini. “He became Freddie Mercury.”