U.S. Army Overturns Convictions of 110 Black Soldiers, Including 19 Who Were Executed

The 1917 executions remain ‘the largest mass execution of American Soldiers by the U.S. Army,’ according to the U.S. Army

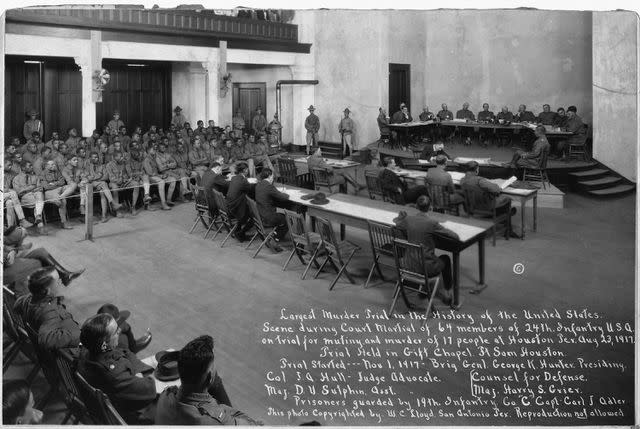

War Department/Buyenlarge/Getty

In what was then the largest murder trial in U.S. history, 110 Black soldiers were court-martialed and 19 of them hastily executed in a trial the U.S. Army now says was riddled with "numerous irregularities."For months, Black U.S. Army soldiers in the Third Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment had endured blatant racism during their deployment to Houston during World War I.

Then on August 23, 1917, a Black woman in the area was arrested, and Cpl. Charles Baltimore, a Black military policeman with the battalion who was concerned for her safety, stepped in, according to a report from the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA), which was first published in 1995.

The White police officers hit the Army man over the head, shot at him three times, and, eventually, arrested him. Rumors swirled that they had killed Baltimore in cold blood, and a riot ensued where nineteen people died, according to TSHA.

In the aftermath, in what was soon after recorded as the largest murder trial in U.S. history, 110 Black soldiers were rounded up and court-martialed. Nineteen of those soldiers were executed, following the trial, which the U.S. Army has just acknowledged had “numerous irregularities.”

Some of those men’s executions were carried out “in secrecy and within a day of sentencing,” according to the U.S. Army, which said that the 1917 executions of 19 Black soldiers remains the “the largest mass execution of American Soldiers by the U.S. Army.” Following the men’s executions, the U.S. Army said they implemented “an immediate regulatory change, which prohibited future executions without review by the War Department and the President.”

War Department/Buyenlarge/Getty

The trial for the 110 U.S. Army soldiers was held in Gift Chapel Fort Sam in Houston in 1917.On Monday in a hallmark decision more than a century later, the U.S. Army recognized the unfairness of the soldiers’ trials and reversed every single court-martial, each of the men’s service “corrected, to the extent possible, to characterize their military service as honorable,” the U.S. Army announced in a press release.

“These Soldiers were wrongly treated because of their race and were not given fair trials," Secretary of the Army Christine Wormuth, who approved the Army Board for Correction of Military Records’ recommendation to reverse the courts-martial convictions said in the statement. "By setting aside their convictions and granting honorable discharges, the Army is acknowledging past mistakes and setting the record straight."

Want to keep up with the latest crime coverage? Sign up for PEOPLE's free True Crime newsletter for breaking crime news, ongoing trial coverage and details of intriguing unsolved cases.

Eli Williamson, the co-founder of Leave No Veteran Behind and a Black veteran who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan as a non-commissioned officer in the US Army and whose family members have served the armed forces in every international conflict going back to World War I, said the decision came as a good surprise.

“There’s a sigh of relief for Black individuals finally being recognized for their honorable service,” Williamson tells PEOPLE. “And also a sigh of relief that we are finally recognizing how difficult it was for Black soldiers to serve honorably at a time when they themselves were not being treated honorably.”

Calling the decision “surprising,” he adds: “Most of the time, you bring these issues up and people don’t want to recognize them. There’s always a place for reconciliation, but reconciliation can’t happen until you right past wrongs.”

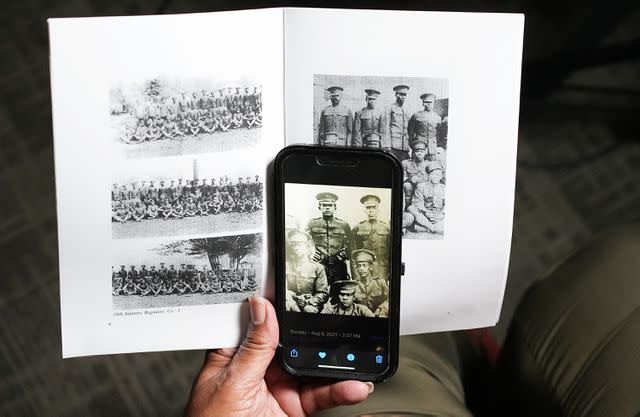

Elizabeth Conley/Houston Chronicle via Getty

Angela Holder, whose great uncle was killed following the Houston riot of 1917, holds a photo of him taken when he was stationed at Camp Logan.The overturning of the court-martials was instigated by dozens of students – some of them veterans – and several professors at the South Texas College of Law Houston, who collected historical documents and requested a review of the decisions twice, starting in October 2020.

On the heels of the school’s petition came additional petitions for clemency for the 110 soldiers from retired general officers, the U.S. Army said.

“One hundred years ago, due process was denied 110 soldiers -- soldiers who were willing to defend their country, but who nonetheless had no voice in their own defense,” South Texas College of Law Houston President and Dean Michael F. Barry tells PEOPLE, adding he was proud of his school’s “part in helping to correct this terrible wrong.”

“The execution of 19 Black servicemen is a notorious incident that is part of America’s long history of racial injustice in the use of the death penalty,” said Ngozi Ndulue, Special Advisor on Race and Wrongful Conviction at Innocence Project. “We can draw a direct line from slavery, lynching, and Jim Crow segregation to this fact. And this is not a problem that we have left in the early 20th century: fifty-four percent of the 195 people exonerated from death row since 1973 are Black. From our cases, we know that racial bias has played a role in the cases of people on death row today. It remains vitally important to acknowledge the wrongs of the past to ensure that we don't replicate them in the future.”

As a result of the change in status to “honorable,” the soldiers’ descendants may be able to receive benefits, by following these instructions and applying through the Army Board for Correction of Military Records or by submitting a DD Form 149, Application for Correction of Military Record by mail to: Army Review Boards Agency (ARBA), 251 18th Street South, Suite 385, Arlington, VA 22202-3531. All applications must include documented proof of the relationship to one of the 110 soldiers.

Family members can also request a copy of the corrected records from the National Archives and Records Administration. Questions regarding these corrections may be emailed to the Army Review Board Agency at army.arbainquiry@army.mil.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.