The Triple 'Murder' of Eduardo Tirella, Gay Confidant of Doris Duke

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

What was the life of a gay man worth in 1966? What if he was violently killed by the richest woman in America in a resort town where she held forth in one of the most impressive estates in a city full of mansions? What if, 96 hours after the homicide, the local police ruled it “an unfortunate accident,” then, days after escaping criminal charges, the heiress, who was worth billions, began giving tens of thousands of dollars to the city?

What if the family of the victim, a 42-year-old war hero and Renaissance Man who had toiled for the killer for years, politely asked her to settle with them for his wrongful death, but she refused at a time when she was making $1 million a week in interest on her fortune? What if the family then sued and she was found liable for his killing? Then after her lawyers so demeaned him at trial, the damages were just $75,000, leaving his five sisters and three brothers with $5,620 each?

Fifty-five years later, what if compelling new evidence was uncovered indicating that the heiress got away with murder — testimony from a previously unknown eyewitness, so credible that it caused the police to reopen the case? Then, five months after that, what if that same police department closed it again, claiming there was “no evidence” to change the verdict they’d reached in the first place?

That may sound like the storyline for a fictional scripted dramatic series on Netflix or Amazon Studios, but all of it is true. The 1966 cover-up of the murder of Eduardo Tirella, crushed to death by Doris Duke outside the gates of Rough Point, her Bellevue Avenue estate, has again been embraced by officials in Newport, R.I., the tony resort city that was the scene of the crime.

Uncovering the Truth

As a Newporter myself, I began my career in journalism as a cub reporter for The Newport Daily News, eight months after the “unfortunate accident,” when the town was buzzing with rumors that Miss Duke, the fabulously wealthy heiress to fortunes derived from the American Tobacco Co., Alcoa Aluminum, and Duke Power (now Duke Energy), had bought her way out of murder charges. The verdict came less than four days after she had crushed Eduardo Tirella, her “longtime companion,” under the wheels of a two-ton station wagon on October 7, 1966.

It was a story I’d always wanted to investigate, but it took me more than half a century to get to it. Then in 2018, I returned to Newport and started asking questions. Soon a remarkable number of surviving witnesses, including many of the cops who’d worked the case, came forward.

By July 2020, my initial findings were published in Vanity Fair. In that 8,000-word piece, I quoted Eduardo’s niece as saying, “She killed him twice. She destroyed his body and then she eviscerated his memory.” That came in 1971 during the wrongful death trial.

At the time, attorneys for the family argued that Eduardo’s career as a Hollywood designer was just catching fire when he told the possessive heiress he was leaving, moments before she killed him.

The year before, Eduardo had earned the equivalent of $351,000 as a set designer on such big-budget features as The Sandpiper, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. He’d just designed sets for Sharon Tate’s next film, Don’t Make Waves, and he could have realized a six-figure income for decades. (This YouTube video is a good overview.)

Duke herself testified at the trial that she “always asked Eduardo’s advice before buying or planning anything for her estates.” He'd counseled her on the purchase of art worth tens of millions and transformed the abandoned greenhouses on her New Jersey property into a spectacular botanical display. She’d even set aside living quarters in each of her estates to keep him close by. But during that trial before a jury in Providence, R.I., Duke’s lawyer portrayed Eduardo as a ne’er-do-well and a “sycophant,” denigrating his reputation as a world-class designer.

The $75,000 in civil damages that she was forced to pay his family didn’t even equal the cost of the Goddard Chippendale highboy she’d bought a month before the trial, at Parke-Bernet, for $102,000 — a record price at the time for a piece of furniture.

But Miss Duke wasn’t content to merely ruin Eduardo’s reputation. She soon began to remove him from the historical record. For decades, the jealous billionairess employed a battery of lawyers, private eyes, and press flacks to sanitize the record of her troubled life. When she died in 1993 at the age of 80 and her obituary sprawled across two-thirds of a page in The New York Times, Eduardo, her art curator and designer for seven years, got one sentence of 34 words.

Documenting His Story for the Record

Right after my VF piece ran, Doris Duke’s Wikipedia entry, which hadn’t been altered in years, was changed to include an entire section on the “Death of Eduardo Tirella,” all of it attributed to my findings. Soon, LGBTQ+ publications like Out and Passport Magazine spread the word.

As more evidence surfaced, I wrote Homicide at Rough Point, a 438-page book with 60 pages of annotations proving not only that Duke killed Eduardo with intent but that her lawyers conspired with the Newport PD to cover it up. To accomplish that, they actually created a fabricated three-page transcript of an “interrogation” of the heiress that never took place. It was nothing more than a “script” of a Q&A that made it appear as if the cops had done their due diligence. But once it went into the official file, the case was closed.

In my book, I made the case for murder in Chapters 32-33 and proved the cover-up by the Mafia-related police chief in Chapters 6-7. Then in July, Bob Walker, the former Rough Point paperboy who confronted Duke moments after the murder, came forward after he read my book and discovered that my findings synced precisely with his memory. The Newport Police Department, which had first closed the case, then reopened it, based on Bob’s confession, which the NPD’s cold case detective, Jacque Wuest, said she found “credible.”

On August 5, I filed a second piece for Vanity Fair. The Associated Press ran a story that went international and The Advocate ran multiple pieces on my book, the distortion of the case by the nonprofit that runs Duke’s home museum, and the case reopening itself.

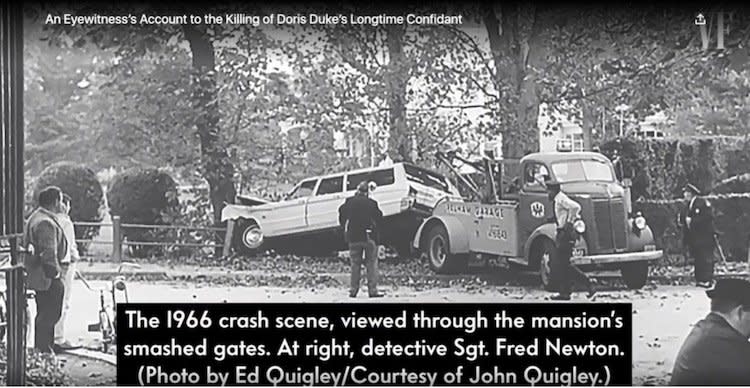

If you access the video of Bob’s interviews with me, compiled by editors at Vanity Fair, you’ll see that his recollection, which he told me was “seared” into his memory, dovetails beat by beat with the fatal sequence of events determined in 1966 by Sgt. Fred Newton, the Newport PD’s chief accident investigator, seen at lower right working the crash scene moments after Eduardo’s lifeless body was extracted from under the wagon. As related to me by Edward Angel, the first officer on the scene, post-crash, Sgt. Newton solved the case within hours and determined that Doris Duke had committed six intentional acts that led directly to Eduardo’s death.

In an email to me on August 2, Det. Wuest pledged that the case would not be “ignored,” and for several months it appeared that justice might finally be done. Over the next 10 weeks, I sent her links to all of my key research, including this email on September 22, in which I set forth the six affirmative acts committed by Doris that led directly to Eduardo’s death. By then, the investigation began to slow down. Det. Wuest was promoted to sergeant, and by mid-September, she told Bob Walker that she’d be leaving on a three-week vacation. Sensing that she was being obstructed from within the department, I compiled a 30-page timeline tracking the many twists and turns of her probe.

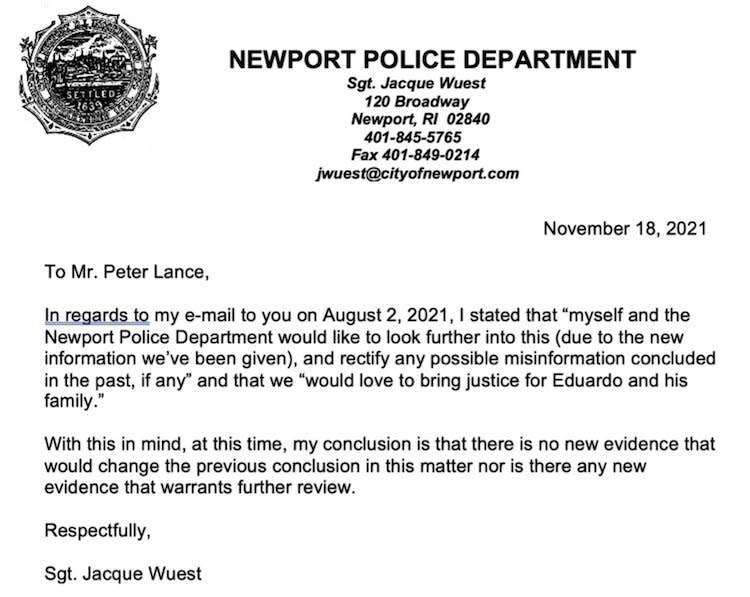

By November 9, when her protracted investigation had entered its fifth month, I pressed Newport’s city manager and the seven-member City Council for answers. Nine days later, on the 139th day of her “re-investigation,” Det. Wuest responded with this astonishing email:

After citing her first email to me stating that “myself and the Newport Police Department would like to look further into this (due to the new information we’ve been given) and rectify any possible misinformation concluded in the past,” then pledging to “bring justice for Eduardo and his family,” she concluded that “there is no new evidence that would change the previous conclusion in this matter, nor is there any new evidence that warrants further review.”

Case closed — again. It was as if Eduardo Tirella had been killed for a third time.

The reaction was swift: “I’ve been on the City Council for more than twenty years,” Council Member Kate Leonard told me, “and I have never seen such a mishandling of a case by a detective who had so much evidence in front of her, disproving the ‘accident’ story.”

Council Member Elizabeth Fuerte texted, “It is our role to ensure that [the] process is followed and no stone was left unturned. If there was [a] cover-up, that too must be exposed and announced. We owe it to this generation. It is our right to know the entire truth.”

Historian Michael Henry Adams, who’d written a piece on the case reopening for The Advocate, emailed this statement to me: “As [a] historic preservationist, I was totally disposed to believe the best about Doris Duke. But Peter Lance’s Vanity Fair article and book convinced me that Eduardo Tirella was murdered, Doris Duke did it, and police corruptly covered up her crime. The case for murder was solid before Bob Walker’s police interview, but his eyewitness account of what happened nailed it. Now, yet again the police have only gone through the motions. It's as if, from the grave, Duke and her money were manipulating the outcome anew. So egregious is this finding, it makes the Newport PD’s pointless reexamination of this, a crime all its own.”

Peter Lance is the author of several investigative books from Harper Collins, including Deal With the Devil. He's also the winner of five news and documentary Emmy awards.