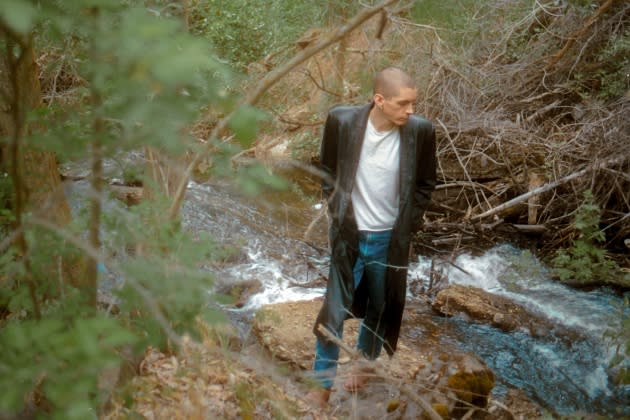

Trevor Powers Had to Face His Biggest Fears to Bring Back Youth Lagoon

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Seven years ago, Trevor Powers cut the cord on Youth Lagoon. In 2011, the Boise native, 22 at the time, had shared his celestial, entrancing dream-pop debut, The Year of Hibernation, with the world, swiftly scoring him Tumblr-era indie reverence. Powers released two more records as Youth Lagoon, the last being Savage Hills Ballroom in 2015, before calling off the project. “There is nothing left to say through Youth Lagoon,” he wrote at the time.

Time away was the antidote. Earlier this year, Powers revived Youth Lagoon with “Idaho Alien,” the first single from Heaven Is a Junkyard, out June 9. He’s returning with “lots and lots of life” under his belt. “Things thrown my way that I wouldn’t have ever chosen,” he says. “But now that they’ve happened, everything looks a little different, feels a little different, tastes a little different.”

More from Rolling Stone

In 2021, Powers experienced a drug reaction to an over-the-counter medication that threatened to take his voice entirely. “It was the first time in my life that my body felt like a prison,” he says. That months-long period, though grueling, forced Powers to recalibrate. “I was so demolished physically and emotionally and spiritually that it felt in a lot of ways like I died,” he says. “It was like every fear that I had ever had in my life came true. And because it came true, it feels like it cured me.”

Heaven Is a Junkyard doesn’t find Powers miraculously void of the anxiety and existentialism that hooked Youth Lagoon listeners all those years ago. He’s still brawling with mysteries: On “The Sling,” which features strings from Rob Moose, he considers the ways that love and memory can both save us and make us suffer. “Heal my hurt/With the love that I gave/Will the loneliness fade?” he asks on “Mercury.” Now, though, his musings are noticeably more serene. “I know I’m gonna deal with fear in different ways throughout life,” he says. “But as a whole, the beast looks so different now, and I’m not scared of it.”

We spoke to Powers about the long-awaited Youth Lagoon resurgence, what his health crisis taught him about self-love, what “heaven” is to him, and more.

Do you have any nerves around returning to Youth Lagoon with a new album after so many years?

There’s really not, because I’m so confident in it. There’s not a single thing on the album that I would’ve done differently. I’ve given it everything that I have, in a way where nothing can steal any of that from me. No matter what people think of it, I know what it means to me. And that’s really all that matters.

That being said, anytime you create something you always hope that other people can attach themselves to it and pull something from it. But the reason I create music is a selfish endeavor — exploring parts of my brain to get to know myself. It’s how I deal with internal shit, or the way that I see the world, the way that I see others. It’s one of the only things in life that makes sense.

In the past when you were releasing music, either as Youth Lagoon or for your solo project, did you feel like there was more pressure?

I had dealt with a lot of pressure, especially after I made The Year of Hibernation, which came out in 2011, which is so bonkers. But after I had made that, being as young as I was, I just didn’t know how to deal with that amount of attention and eyes on what I was doing. Obviously a huge part of me was psyched that people cared, but then another part of me was completely overwhelmed because I just didn’t know what to do with that.

I came out with Wondrous Bughouse in 2013, and that was a huge turning point, because there were a lot of people that felt like I should only do this one thing. It felt a little like I was being treated like one of those toy monkeys with cymbals, and they only wanted me to crash the cymbals together. It really drove me fucking crazy because I was moving on. When I do something creatively, I’ll never do that same thing again, because it already exists, so why would I, right? Moving on to Wondrous Bughouse, that was part of me saying, “OK, what else can I do? How else can I fail? How else can I learn all this stuff?” Which is why I got into music. I just felt like I was misunderstood, which was frustrating. That continued with Savage Hills Ballroom. The frustration grew and grew and grew to the point where I could no longer even identify with this thing that I had created because of how other people were viewing it. The whole thing just started feeling kind of icky.

And then you started making music under just your name for a while. How was that?

After I killed off the Youth Lagoon moniker in 2015, I made two albums under my own name. Mulberry Violence came out in 2018 and Capricorn in 2020. Those were incredible because it felt like I didn’t have eyes on me. Obviously there were some people that were still paying attention, but it was a very different story. It felt like going to college. I had the freedom to just try things and there was no worry.

I had some song ideas that I was tossing around maybe four years ago, and I didn’t really know what they were. Nothing had a shape yet. Then I had this huge drug reaction at the end of 2021, and my whole life flipped upside down. Every path that I thought I was walking down just no longer existed.

To the extent that you’re comfortable speaking about that experience, what did that health scare reveal to you about life and music?

I took an over-the-counter medication and it fucked with my digestive system so bad that it created essentially a geyser of acid in my stomach that would soak my larynx and vocal cords to the point where I couldn’t talk for really long periods of time. I had seen multiple specialists, ER visits, I had an endoscopy, colonoscopy, you name it. Every single test done. Doctors couldn’t figure out what it was that this medication did. It went on for months and months and months and months. And to be honest, I’m still healing from it. I’m probably at about 90 percent.

Like a lot of people, there’s been suffering in my life before. I might’ve had a shitty day or shitty week, but never to the point where the suffering was so extended. For months, I was in a very dark place. I was seeing a couple therapists and trying to get a grip mentally, because I knew that once I could find some calmness in the storm, that’s when true healing would begin.

One of the therapists asked me, “What are some things that you love about yourself?” It was such a hard question for me to answer that it made me start crying. It was either later on that day or the next day, I was thinking about when I had killed off Youth Lagoon. To re-embrace this part of me that ended up feeling like it was getting polluted or I didn’t identify with, and to reintroduce it to who I was as a person now, felt like the truest form of self-love that there was. That was the turning point. It was when I had started accepting these parts of me that I had abandoned because they felt old. I started piecing them back together, uniting them with these ideas that I was wrestling with as a person now. It felt fresh when I started combining those two worlds.

One of my favorite songs off of your new album is “Trapeze Artist.” Correct me if I’m wrong, but it seems like the lyrics are pointing to that experience specifically.

No, that’s totally correct. That’s one of the few times in the album where I actually talk about the experience blatantly. The rest, the emotion is there, but it’s through other lenses.That song is very specific.

With the other songs on the record, are you telling stories through characters?

I’m playing a lot with the combination of fiction and non-fiction. I’ll take things that people around me might have said or things that are based on very real-life scenarios, but then put them through this lens of playing around with characters while at the same time leaving in things that are directly from me.

For instance, in “Idaho Alien,” the narrator of that story is me. The chorus was written during the peak of everything I was experiencing. “I don’t remember how it happened/Blood filled up the clawfoot bath/I will fear no frontier.” To be honest, that was how I was able to exorcise some of these demons of wanting to escape my body when it felt like a prison.

When you tell these stories, do you find it a little safer to use these narratives? Does that feel more comfortable to you rather than just heart-cut-open confessions?

I don’t know if it’s necessarily safer. It’s just more fun. It gives me more to play with. Even songs like “Idaho Alien” or a lot of the record where I’m dealing with a lot of dark imagery and heavy subject matter, I’m having fun doing it.

There’s a lot of joy in it. That’s one thing that I think gets lost on people, is they can get so sucked into something having a tone of emotional distress, and they think that you’re wallowing in it. I love getting things off my chest; it makes me way lighter of a person. But the movies, the books, all that stuff that I gravitate towards are the things that are dark. I have a lot of fun playing around in those worlds.

What kind of music, books, or movies have inspired your writing?

Lots of filmmakers. Wim Wenders — his road movie trilogy has been huge in this whole process. Terrence Malick, Sofia Coppola, Andrei Tarkovsky. I feel like I can rip off movies all day long because it’s a different art form. You can do whatever you want with it. I listen to a lot of music, but if I’m listening to one artist too much and I end up emulating some of that, it’s so much more obvious when you’re stealing someone’s shit.

There’s all kinds of records I’ll fall in love with, but I tend to pull way more from movies and books. I love 1950s crime novels, people like Jim Thompson and that whole world. I’m always trying to devour everything around me.

In “Mercury,” one of the lines asks, “Does heaven glow like mercury?” And the title of the album is Heaven Is a Junkyard, so that imagery runs throughout the record. What is heaven to you?

It’s a super fucking hard question. There’s all kinds of spiritual and religious themes and symbols and imagery that I love playing with because there’s so much there to unpack. These symbols already come so fully loaded. That makes it way more fun. Even words like “god,” there’s so many different ways to take that word. For some people, there’s a lot of baggage, history, and trauma related to church.

I personally was raised in a Christian church. I haven’t stepped foot in a church in years. Through therapy I’ve had to work really fucking hard to get things out of my system. I’m also so grateful because it showed me that there is such a beautiful mystery that we’re surrounded by, and that’s what I’m in love with: that unknown veil. How do I get closer to it? How do I try to understand it? That drives all of my work. And you can call that whatever you want. You can call it God, you can call it nature, you can call it mystery, but I think it’s all saying the same thing.

It might sound trope-y to say, but I do think that Heaven starts right now. People are so consumed with “Heaven is up there” or “Heaven is far away” or “Heaven is this place that we’re heading to.” I think that Heaven does start right now and sometimes the people that lose sight of that most are the people that are the most religious because what they’re spreading on earth is hell.

There’s a theologian I love whose name is Richard Rohr, and he quotes Catherine of Siena, saying, “It’s heaven all the way to heaven and hell all the way to hell.”

You’ve said that in the past, you’d write about faraway things and that was your way of running from home, but the best material has actually been right where you are. What is home to you?

Home is where love is. My family, for instance, we’re not radius-based people. I have three brothers. We all live far away from each other, but it doesn’t change that sense of home being this connective tissue, this unbreakable twine. So when I see my older brother in Seattle, I feel like I’m home. Or when I see my youngest brother on the East Coast, I feel like I’m home. Now I’m an uncle. I have shitloads of nieces who I love so much. One of them is actually the little voice on that opening track “Rabbit.” She lives a three-minute walk from me. That’s where home is. It’s different for everyone, but everyone has that good stuff somewhere.

What do you most hope that listeners take away from this album?

I really don’t want people to feel alone. That’s my big thing. Throughout this whole journey of writing it, I’ve been coming to terms with the realization that when you do spend a lot of time alone and getting to know yourself, then ironically, that’s when you start feeling the least alone. Our society is so saturated by distraction, social media, artificial friends, right? It tends to stretch us in these ways that we feel more alone than ever. The more that I’ve had time to meditate every day, be with myself wholly and fully, that’s when I start realizing, “Oh wow, I’m not alone.”

I sense this greater thing, this unknown love that’s always there. That is a throughline throughout all the music and that’s the main thing I want people to pick up on. Even though there’s darkness, you’re only in the darkness because you’re heading towards the light.

Best of Rolling Stone