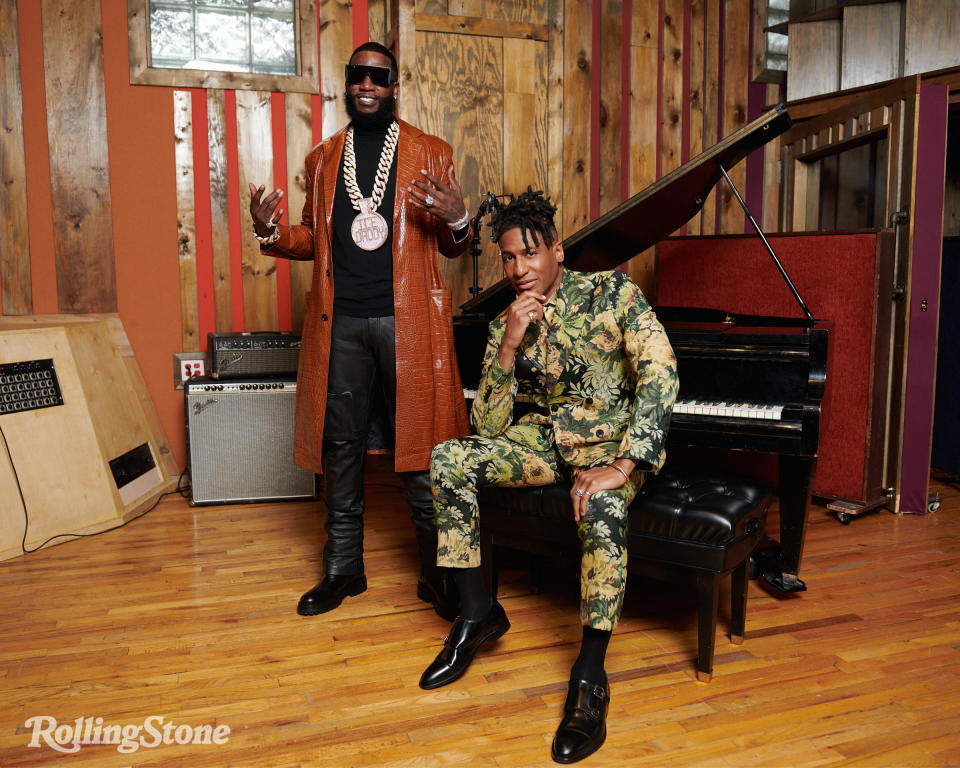

Trap God, Grammy King: Gucci Mane and Jon Batiste Tell All

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

One has two degrees from Juilliard, and the other went straight from the streets of Atlanta to the studio, where he helped invent trap as we know it. They come from wildly different musical worlds, but Jon Batiste and Gucci Mane found plenty of common ground when they came together for an onstage discussion at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn as part of Rolling Stone’s first-ever Musicians on Musicians live event. Earlier that same day, Batiste scored five Grammy nominations for his latest album, World Music Radio, featuring guests from Lil Wayne to Lana Del Rey, while Gucci was still riding high from his own strong new album, Breath of Fresh Air.

They both grew up in the South, with Gucci spending his early childhood in Bessemer, Alabama, before he moved to Atlanta, and Batiste coming of age in a Louisiana musical dynasty. Batiste was a genre-crossing musical rebel from the start, and he’s gone far afield from his jazz roots; 2021’s gospel-drenched We Are took home Album of the Year at the Grammys, while World Music Radio is a concept album that ranges from pop to hip-hop. Gucci, meanwhile, is an undisputed legend, one of the most influential and long-running rappers of this century, with no fewer than 77 mixtapes to go along with his 16 studio albums.

More from Rolling Stone

'American Symphony': Jon Batiste Gave Us the Best Music Doc of the Year

Jon Batiste Celebrates an Enduring, Transcendent Love on 'It Never Went Away'

Jon Batiste Announces First-Headlining Run 'Uneasy Tour: Purifying the Airwaves for the People'

They’ve both kept creating while facing strife in their lives. As chronicled in an upcoming documentary on Netflix, American Symphony, Batiste’s wife, Suleika Jaouad, recently battled cancer even as he worked with an orchestra to stage his very first symphony. And as Gucci writes in his fantastic memoir, The Autobiography of Gucci Mane, he struggled with drug addiction and the criminal justice system, but emerged from prison fit and sober in 2016, immediately hitting new career heights.

At the end of their conversation, Batiste took the final step in crossing any musical distance between the two artists by sitting down at a piano and turning one of Gucci’s greatest songs, 2009’s “Lemonade,” into a dizzying improvisational piece.

One thing both of you have in common is improvisation — Gucci is known for freestyling some of his biggest songs at the mic, which started around the time of the track “East Atlanta 6.” How does that art of going in the studio with nothing and coming out with something great work for you?

Gucci: With me being in the zone to make a song and just freestyle it, at that time of “East Atlanta 6,” that was like when I was 27, 28, 29 years old. Youthful days. I had a lot of energy, and it just goes along with that period of time in my life. Now, I write my raps down, but I do it faster, because I’m more deliberate when I make something. But back then it was just like, whatever I make — quick, just make it. Being spontaneous was a challenge, and it was fun. It was almost trying to make something, then the next day, you see what you made from the night before. It started turning into a thing, trying to impress yourself.

Batiste: A lot of times, I have an idea from something that happened in life or somebody I met. I feel like since we’ve been talking, I got beaucoup ideas already! You get ideas and then you try to make them real. And then I go into the studio and I use whatever I can, whether it’s the piano, drum machine, my voice, the guitar, anything that will make the vision come to life, and I also bring in people who I think will bring that vision to life. I’m always thinking like I’m making a movie, and then sometimes you have to cast the movie.

And then when the vision hits, it hits. I grew up with all of the musicians in my family being self-taught — street musicians, people who play music just for fun. And when I went to school, I was the first person in my family to go to college for music. So, I felt like a fish out of water in that environment. But I stole a lot of stuff from it and incorporated it with what I already had. That’s when I started to build my own approach. I don’t like to think about it — it has to be intuitive. But I do learn from classical music and all the other things that I’ve studied.

Gucci: For me, I wasn’t a musician. I came up with the producer Zaytoven, who was my partner. He played music in church, and I had another friend who played in the marching band that made beats. I always felt like they were so talented, and I wished that I could learn how to make beats. But I didn’t know how to make a beat. So, by the time I said I was going to be a rapper, it really was more of a challenge. And even with the freestyle, it was just like shooting in the gym. I was getting my reps up, shooting a thousand shots a day, trying to really practice to be a better rapper. And I knew that’s what I was doing, but at the same time, I was building up the confidence to say, “Hey, as I’m learning to be better, I’m going to put the music out and let the people judge me.” ‘Cause most entertainers are scared to be judged. They’ll hold it so close to their chest. With me, I had this free spirit: I’m gonna rap. Some people will critique it and say it’s not good, or I sound this way or that way. And I just build on that and take it. And keep going.

Batiste: I just think about doing me and expressing what I really believe in. If I truly believe in it, then I’ll feel it. And if I feel it, I believe that others will feel it too. I’m not thinking about breaking rules; I just consider it inspiration.

I wanted to ask both of you about a specific song. For Gucci, I want to go back for a minute. Can you tell us how you made “Lemonade”?

Gucci: I used to record in Vegas at this casino called the Palms. And it just so happened that when I was at the studio, my old manager — Coach K at the time — also used to manage and do some business with the producer Bangladesh. He put us together. Bangladesh was already in Vegas, doing something else at an MMA fight, but we met at the casino. I just made the song talking about all yellow stuff. He really didn’t understand where I was going with it. But it kinda grew on him. He took it home and put his kids on it for the hook part of it. And then he brought it back to me, and then I made a second verse to it. So that’s how that came about.

And Jon, I had to choose between the song that was nominated today for Record of the Year and the song that was nominated for Song of the Year. I couldn’t decide which one. But let’s go with “Worship,” which was nominated for Record of the Year today.

Batiste: I was working with John Bellion, who’s a producer, songwriter, and artist himself, and we were talking about how to make something that felt like a spaceship landing and then a robot growing a heart. Like a robot becoming human. So that was the vision. And we started messing with sounds. And then once we had that intro, it felt like it was time to have it land somewhere. So then the vision was, it’s landing in the rainforest.

And it’s a release, a catharsis, almost like a revival or something. That was how I wanted to start. The concept of the album is a radio broadcast, so the spaceship lands, and the radio broadcast starts, and the robot turns into a human. And then we’re in a rainforest.

Making music for awards is not something that I ever did. I wouldn’t recommend doing that, whether you have them or not.

— Jon Batiste

Gucci: I like that. So dope.

Jon, needless to say, the Grammys love you, justifiably. Gucci, you finally got your first nomination in 2019. It’s no secret that Grammys and award ceremonies are slow to recognize a genre like trap, slow to catch up with hip-hop. But how important is that institutional recognition? Jon, you got up onstage when you won last year and said, there is no best artist.Gucci: I’ll let him take that one.

Batiste: I think the biggest blessing of recognition is when your peers respect what you do and it feels like you’re adding to the culture and whatever era you’re in. And ultimately, it’s another way for the work to be recognized and for it to affect people’s lives. I think it’s a great thing because it just elevates. If what you’re doing is from a pure place, it just elevates it. And it allows for it to do what it do. I believe in that. Making music for awards is not something that I ever did. I wouldn’t recommend doing that, whether you have them or not.

Jon, you worked with Lil Wayne on your new album, and even got him to play guitar. Obviously, you’ve had previous experience with hip-hop, but I was curious what that taught you about how rappers work and what questions maybe that raised in your mind for Gucci.

Batiste: Wayne and I grew up in the 17th Ward, in Hollygrove [New Orleans], about three minutes from each other and didn’t know it. But the cultural connections of living in the same place and coming from different musical perspectives, all of that coming together, it created something that I never would have imagined. Just the way he would flow over those kinds of chords and that kind of beat, I had never heard him do that. And I had never thought to do that until we were in the room together. So Gucci, what kind of sound would you like to explore?

Gucci: I’m open to all kinds of music and just being creative. I don’t like to be put in no box. I like the challenge of trying to do new sounds and new things.

You’ve both done some acting. What skills transfer back and forth between music and acting, and what do you learn from one that might be helpful to the other?

Gucci: It’s still using your words and your voice, so you still have to remember your script and stay in character and be punctual, be on time. There are a lot of people involved, it’s a teamwork thing to make it happen. It’s just like being in the studio. Gucci, is it really true that during a certain scene in Spring Breakers, you were falling asleep and had to be woken up?

Gucci: [Laughs.] I was full of that lean.

Batiste: I agree, it’s discipline, just showing up, doing your thing, and also being yourself. Finding your own voice in it. Because there’s a script, and once you learn that, once you learn how to hit the lights right and the marks, and just get comfortable, then that’s when you can discover some stuff. That’s my favorite part. And that’s like music. When I worked with Spike Lee [on 2012’s Red Hook Summer], Spike was like a military drill sergeant. He gets the most out of that crew. And the actors, it was my first experience being on the set with Spike. I had done some stuff with Treme on HBO, the David Simon show, but doing a movie is different. You gotta wait a lot, and then you gotta be on when it’s time to hit. With Spike, you don’t want to not be ready. So that was interesting and great for my first movie. It was like a trial by fire.

So many great American musicians come from the South. What did each of you take, musically, from your roots there?

Gucci: To me, it’s the parents, it’s your grandparents, it’s your aunts and uncles. And it’s just passed down as what they listen to. It’s all the musicians, it’s the church. It’s all that.

Jon Batiste: Yeah, wow. I love how you say it’s the parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles. It’s just life. That’s what’s coming through the music. The way we live in the South is very different. Especially now that we’ve traveled to different places, and there’s nothing like going back. Nothing feels like that. So I think we channel feelings, we channel all that, and then imagine for generations and generations in the lineages; it just builds on itself. By the time you get to us, it’s almost like its own institution. You don’t got to go to music school to get that. You just live that. You have something to sing about.

Gucci, in your book, you said that in your twenties, when you’d go back to Alabama, it would drive you crazy. It was way too slow and country for you. But now, at this point, are you able to go back and relive a little bit of your childhood and appreciate it? Or is it still too slow and country for you?

Gucci: That’s a great question. And to give you a sincere, honest answer, I have mixed feelings when I go back to my hometown of Bessemer, Alabama, because there’s not a lot of opportunity there. And I don’t even want to speak harshly about it because both sides of my family are there. But I’m one of those people who, if I don’t see opportunity, I’ll leave the town. Maybe I get that from my mom. If there aren’t any jobs here, then I’ll just uproot and move somewhere else.

I have this kind of nomadic approach to life. So even though I, say, I don’t want to disrespect my family because I love them and that’s my home, to me, I’m a 49er, I’m going where the gold at.

Both of you, in your own ways, had really early exposure to music. I wonder if both of you could talk about who your earliest music heroes were.

Gucci: It’s easy for me because I had an older brother. My musical influence was always whatever he thought was cool, early on. In Alabama, it was LL Cool J and Doug E. Fresh and Slick Rick and Kool Moe Dee and Salt-N-Pepa.

But as we moved to Atlanta and grew up, it started being 8 Ball and MJG, the Hard Boyz, Ghetto Mafia. Kilo Ali, just whatever was popular at the time. And I always wanted to be that kid in school who knew about things before the other kids did. So it was like, “Oh, y’all listen to that? Y’all listen to MC Hammer? I’m listening to Scarface or the Geto Boys.” That’s how I used to feel when I was able to get my brother’s cassette tapes and learn about them. I would go over and talk to other kids who had older brothers. It’s like we had something we knew about.

Batiste: Yeah, as far as rap music in New Orleans, there was a real movement with Master P and the Hot Boys. Eventually, by the year 2000, Juvenile, Mannie [Fresh], Wayne, and that was just ubiquitous. It was everywhere. That sound was like basketball games out of car windows, cookouts, and any dance you ever went to. And so that was happening, as I said, I grew up between 17th Ward, New Orleans, and Hollygrove. And also in Kenner, Louisiana, which is kind of a provincial suburb country, it’s almost rural. So when I was there, I was playing video games and the music from the video games was actually some of my early influences apart from my family, my dad, Alvin Batiste, and the Marsalis family, the Nevilles, [pianist] Henry Butler — like all the musicians.

I started playing music very late, actually. I didn’t start playing the piano until I was about 12 or 13 years old. So before that, I was just a kid listening to what was on the radio, listening to video games. I realized I had a good ear because I would remember the themes from the game and I would be able to play them on the piano just by dabbling. I would hear it and be like, “Oh, I could try to change this note and that note.” Then that started to become composing music. So, the combination of the video games, avant-garde jazz musicians in New Orleans, funk musicians, and the Hot Boys and Master P and Mystikal were my early influences.

Some of my best music [came out] when I was going through real challenging parts of my life. But do I want to go through those times to please my fans? Hell no. — Gucci Mane

I remember hearing when you went to Tokyo for the first time, you were excited because it was the home of video-game music.

Batiste: Man, oh man. Japan, crazy. I loved it. I loved it so much because for me, that’s very nostalgic. That’s the music that I grew up with in a way. I wrote letters to those composers. Yoko Shimomura, Nobuo Uematsu, all those people who wrote those themes. I went to meet them.

You both had hard times but kept creating through them. And some people create best in the face of strife. How do you see that working?

Gucci: I think once I put it on my mind that I was gonna leave the streets and start being a rapper — good days, bad days, every year I’m putting out music. I’m gonna be productive, I’m gonna be prolific. But some of my best music, some of my most acclaimed albums were like ’05, ’06, when I was going through real challenging parts of my life. In 2012, 2013, I was still putting out music and some of that music was expressing what I was going through. And those were hit records. But do I want to go through those times to please my fans? Hell no.

You would choose a happy life instead if you had the choice?

Gucci: Yeah, I’ll take that. I’ll take it.

Batiste: I 100 percent echo everything Gucci just said. For real, I think hard times inspire you to make something that you wouldn’t make if you weren’t under the pressure of that. But I also think you can make great stuff and be super happy in your life. And I think that’s a myth that I don’t really buy into. I think we have to stop the myth of the tortured artist having to be so under it.

Gucci: I agree with you.

For both of you, is music a lifelong thing, or is there a point at which you’re going to transition into something else?

Gucci: I personally feel like we’re living in the future, and a lot of people just aren’t aware of it.

And the reason I say that is because, about the longevity thing, I come from the past. I come from physical copies of CDs back in the day and giving out mixtapes hand to hand. So artists [now] don’t even understand that you don’t even have to make a physical copy. You can basically just record your ideas and put them out there and make endless amounts of tapes.

As soon as they started making it so we can download stuff and it didn’t have to be physical, I started flooding the streets with tapes. So with the longevity thing, I feel it’s not a race. It’s a marathon. So you gotta patiently keep putting out music and work this shit like a 9-to-5. And if you do that, then I feel like you’ll have success.

Do you want to be making albums when you’re 70 years old?

Gucci: 100 percent. 100 percent because that’s what the game has evolved to. You got Jay-Z in his fifties and Snoop and E-40 and Nas. All these artists are amazing. Not only just making music, they’re making money. [Laughs.] So they’re giving you the blueprint for artists in their forties and their thirties of what could be. And that’s how the game is. You keep pushing the envelope.

Batiste: There’s too much to figure out. Too much to explore. I don’t know as much as I would like to know about my own potential. So that’s what keeps driving me.

Photography direction by EMMA REEVES. Batiste: Hair by JENNA ROBINSON. Makeup by JESSE LINDHOLM. Styling by WAYMAN + MICAH for FORWARD ARTISTS. Gucci: Styling by JASON REMBERT. BTS Videography by MIKE PIANTADOSI. Photographic assistance: JOSUE HURST. Batiste styling assistance by YNES TRABELSI. Mane styling assistance: KIRSTEN MCGOVERN and ORVILLE REID

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ settings: { plugins: { pmcAtlasMG: { iabPlcmt: 1, } } }, playerId: "4d2e11b7-633a-417a-962e-4b7e105b5998", mediaId: "2c408741-d189-4a51-909d-86d8754d2286", }).render("connatix_contextual_player_2c408741-d189-4a51-909d-86d8754d2286_1"); });

Best of Rolling Stone