Top Iranian Filmmakers Strike A Blow For Women’s Rights And Democracy Movement

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The winds of change are sweeping Iran as the ‘Woman Life Freedom’ protests, provoked by the killing of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini last September, continue. Here, four Iranian disruptors talk about their struggles, their acts of solidarity for the pro-democracy movement, and their hopes for the future of their country.

Marjane Satrapi

Marjane Satrapi, who was 9 years old when Ayatollah Khomeini came to power in 1979, recalls taking to the streets with her politically active parents to protest against the imposition of the hijab. “My mum went to demonstrate, and I went too, and so did my dad,” recalls the graphic novelist and filmmaker. “He was one of the very few men; they didn’t understand at the time that women’s rights are society’s rights.”

More from Deadline

Satrapi’s parents sent her to Europe to study as a teenager and encouraged her to make her permanent home there. Satrapi captured these experiences in the graphic novel series Persepolis, which she turned into an animated feature in 2007. Having lived in exile in Paris since the early 1990s, Satrapi has often received threats and slurs from the regime over her work.

“I’ve been called a liar and a spy. I’ve learned in life not to be scared,” she says. “It’s not that you don’t feel fear; you feel the fear, but then you decide whether you care about it or not. It’s not that I’m fearless or careless but there are kids in my country who are being shot and they are 17 years old, while I have lived for more than half a century.”

Satrapi recently organized a flash mob in front of the Iranian embassy in Paris in solidarity with five Tehran teenagers who were arrested for posting a TikTok dancing to the Rema and Selena Gomez track “Calm Down”. She is also working behind the scenes with a team of young diaspora lawyers looking at ways to go after members of the regime through the courts.

“We artists must be humble but doing nothing is worse, being indifferent is worse. I don’t think what I’m doing is huge or immense but I have a voice, I have a face and I’m known in France, I’m just doing what I have to do,” she says.

She would like to eventually make a film about what happened to her country under the Islamic Republic regime. “I need time to understand how this happened and what made these people do the things they did to their own population. I hope everyone will go to court. You can’t wash blood with blood. You need clean water. This is called putting people on trial, to understand where it comes from, to really cut the roots.”

The filmmaker is convinced that the protests herald the end of the Islamic Republic government: “I’m not a psychic. It’s not six months, but it’s not five years. It’s somewhere in between… We have a saying in Farsi about cutting somebody’s head off with a silk thread. Instead of cutting with a knife, you take a silk thread and slowly, slowly, little by little. This is what the Iranian people are doing… at first, nothing happens, it’s a little bit red and then at a certain point, you cut off the head.”

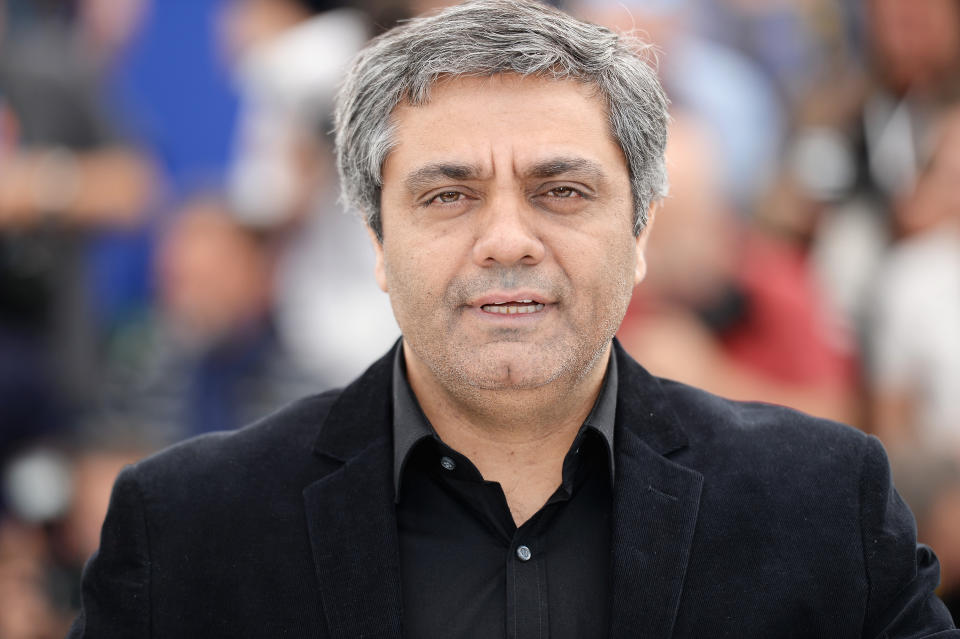

Mohammad Rasoulof

Rasoulof has been in the crosshairs of Iran’s hard-line Islamic Republic government throughout his career for challenging its draconian rule with his work.

Once a Cannes regular with award-winning films such as Manuscripts Don’t Burn and A Man of Integrity, he has not been allowed to leave Iran since 2017. The 2020 Berlinale Golden Bear for his last film, There Is No Evil, was awarded in his absence.

He is currently home after a six-month stint in Evin Prison after being arrested with fellow filmmakers Jafar Panahi and Mostafa Al-Ahmad. The trio were detained prior to the ongoing Woman Life Freedom protests for signing a petition titled “Lay Down Your Arms” calling on security forces to exercise restraint in relation to popular protests.

Following his release, Cannes had hoped to get him to France this year to participate in its Un Certain Regard jury, but Iranian authorities kept his travel ban in place.

While in prison, Rasoulof contracted a gastrointestinal illness due to the poor sanitary conditions from which is still recovering. “I was sent to the hospital for surgery out of necessity. I was in a hospital bed for two weeks, under 24-hour prison guard watch,” he says. “They handcuff and shackle sick prisoners.”

News of the Woman Life Freedom protests, which broke out after his imprisonment, percolated into the prison. “We would receive the news via official and unofficial sources. Family members of prisoners would deliver the censored news which you couldn’t find in the papers or on TV to us, during their visitation times or by phone calls. We would even secretly see photos of protests sometimes. We were truly impressed by this young and defiant generation’s activities,” he says.

“Some of the young protesters who were arrested by the authorities were transferred to our wing. We would talk to them to figure out what’s happening outside. There was obvious excitement among all the political prisoners.”

This excitement was tempered with more level-headed discussions with prominent political commentator and journalist Saeed Madani, who is serving a nine-year sentence in Evin, he reveals. “We would talk together about the social upheavals from a realistic point of view, away from emotions and sentiments.”

Despite everything, Rasoulof says he has no regrets. “I’ve never regretted that even in the worst situations, even when I was in solitary confinement or during the interrogations, I felt no remorse. I wish the political situation could allow different voices and criticisms to be heard on a variety of issues to achieve some sort of reform. But we all know that such a political situation does not exist. The regime is corrupted and dysfunctional. This kind of cinema might not be what I like the most, but it’s my priority.”

Golshifteh Farahani

Actress Golshifteh Farahani fled Iran in her late 20s after she got on the wrong side of the government for appearing in Ridley Scott’s 2008 spy thriller Body of Lies without a hijab.

“After 15 years, I feel like I lost an arm, and this arm, it will never grow back,” she says.

Remaking her life in exile was a struggle she recounts: “It’s like being reborn again. You have to learn a new language, a new culture. You have to learn everything from zero.”

The actress has since rebooted her career in Europe and the U.S. and now uses her fame to highlight the struggles of her people back home.

A few years into her time in Europe, Farahani told The Guardian newspaper that she hated politics. Now, a decade on, she has come to terms with the fact that politics is part of her life.

“As a person coming from the Middle East, whatever you do, becomes political. You walk, it’s a political walk. You talk, it’s a political talk. But sometimes, it’s just what it is. It’s not a message. It’s not a symbol. It’s just what it is,” she says.

“But, of course, recently with what has happened in Iran, I took a very clear position for the first time after 15 years, to directly stand with the people of Iran on their side, and somehow be the reflection of their voice, to translate it, scream it… We need bridges between the West and East because there has been so much separation and we, the people, need to find a way to connect.”

Farahani says she is impressed with the new generation of youngsters leading the protest, which differs from her own, which grew up in the shadow of the revolution and during the 1980 to 1988 Iran-Iraq war.

“We were fearful, very, very fearful. If we are seeds planted in the soil, we prepared the soil and they managed to break through and grow towards the light. They are just fearless and courageous. I look at them with a feeling of appreciation and awe. I can’t describe it. It makes me emotional when I see their courage.”

Last October, Farahani joined Coldplay on stage in Buenos Aires for a performance of Grammy-winning Iranian protest song “Baraye” by imprisoned singer-songwriter Servin Hajipour.

“That was one of those moments that really changed my destiny in life, that I never chose or asked for, like working with Ridley Scott or my departure from Iran. I got a phone call. It was very complicated. I was in South Africa but there were no direct flights to South America, so I had to fly via Europe and got there without time.”

“The irony is that Coldplay was the soundtrack of our teenage years,” she says. “When I was 15 or 16, this is all we were listening to. I have so many videos of myself singing those songs, so going there and singing in Farsi was as if this revolution had somehow given me back my language and the Iran I lost in these 15 years. It was one of the most remarkable experiences of my life. Chris Martin and his crew, it was wonderful and incredible that they made this gift to the people of Iran.”

Zar Amir-Ebrahimi

Zar Amir Ebrahimi, who won best actress in Cannes last year for her performance in Holy Spider, has been busy on the festival circuit these last few months participating in panels on the future of Iranian cinema in the light of the Woman Life Freedom.

However, the actress and director, who fled Iran nearly 20 years ago, wants to move the discussion onto the more practical matters of fund-raising to support Iranian filmmakers who are trying to boycott film funds backed by the Islamic Republic.

“We’re asking people in Iran not to work with the money of the government and the Revolutionary Guard, but we need to find a solution for them,” she says.

The protests have brought to light that nearly all Iranian cinema and TV was financed directly or vicariously by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corp, which has interests in nearly every aspect of the Iran’s economy.

Making films and TV shows outside of this system is very hard. Amir-Ebrahimi says some film professionals are leaving the business rather than tap into state funding citing the example of Payam Dehkordi.

The popular actor announced last October that he would not appear in any new television or cinema shows out of solidarity for the protest and has recently opened a bakery.

In the meantime, indie films, which received funding prior to the protests, are now in the crosshairs of festival bans on Iranian government-backed films.

“We need to start talking about fund-raising,” she says. “That’s what I am trying to do. Sometimes I feel alone but I am trying to talk to colleagues outside of Iran, to see if we can find solutions.”

Amir-Ebrahimi also highlights the struggle of Iranian diaspora film professionals as they build new lives outside of Iran and try to continue working in cinema. She cites the example of Holy Spider cast member, the veteran actor Mehdi Bajestani, who has been living in exile in Germany since the film’s Cannes premiere.

Holy Spider would have been difficult to make without his participation, she says.

“He was so brave. When I asked him, ‘Why are you doing this? Do you know you’re taking this big risk?’ He said, ‘You know Zar, I think for once in my life, I need to do something good without censorship, without control. I managed to finally do something important. Anything that comes after I don’t mind, even if I lose my life in Iran.”

The veteran actor, who had a career back home, is now finding it impossible to secure parts in Europe.

“The diaspora community in Europe also needs help. What can we do with empty hands, we need to do more than just talk and participate in panels,” she says.

Amir-Ebrahimi notes her own difficulties in getting her own directorial debut, about her final year in Iran, off the ground.

“It’s been years and years that I’m working on it and I just can’t get the budget together. It’s in the Persian language and there are no funds for these kinds of projects,” she says.

“There is this new generation of cineastes outside of Iran, now almost everybody is out. We need this solidarity to find a way to make movies.”

Best of Deadline

Cannes Film Festival Photos Day 3: Harrison Ford, Phoebe Waller-Bridge, ‘Le Regne Animal’ & More

2023 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.