It Took Me 30 Years To Come To Terms With Half Of My Identity

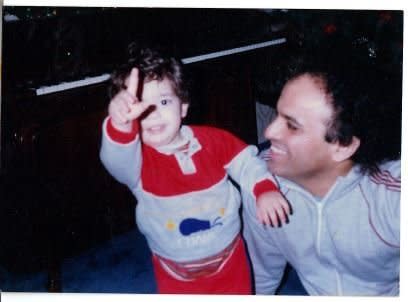

My father is Indian, and my mother is half Puerto Rican, half Italian. As a toddler, it never occurred to me that having olive skin might not be the norm in an American family.

My mother raised us partially Roman Catholic, and every night we prayed to Jesus; my father occasionally took us to the Hindu temple, and we’d pray to Ganesha. For dinner on Mondays, my mom cooked meatloaf and mashed potatoes; on Tuesdays, she whipped up chicken curry and basmati rice. I thought there was nothing unusual about my life until I attended public school.

On my first day of kindergarten, faculty members pulled me and a girl of Egyptian descent into a private room and asked us if we spoke English. I was only 5 years old, and I thought nothing of it. I didn’t realize how “special” I was until children began picking on my foreign name. It didn’t help that my eyebrows were as thick as my curly hair.

I began to learn that blending into the crowd was never going to be an option. As years passed, I began to tell my mom, “I wish I was normal! Why couldn’t you have named me Nick or Joe or Steve or Mark instead of Raj?”

Even within the Indian community, my brother and I stuck out. At parties, we’d be the only light-skinned children in the bunch. The brown-skinned children found similar reasons to exclude and disassociate with us. It became evident that we were not one of them. Even the Indian wives, who were no different than any other group of catty socialites, spoke only in Hindi around my mother as a sign of rejection from their clique. I became resentful of my desi, or Indian, side. I felt like an outcast, a reject, a loner.

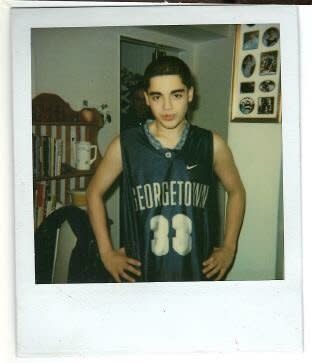

Sept. 11 happened during my first week of high school, followed by hatred toward anyone with brown skin. As awful as it sounds, I considered myself lucky because I had fair skin and therefore was not an easy target. The few other Indian and Sikh kids at my school had it much worse, from bigoted name-calling to physical harm.

If teenage protocol promoted conformity, I stood no chance of dating the Ashleys or Jennas of the kingdom. My first girlfriend was Indian-American, and in a strange way, I felt a temporary level of comfort around my kind. In high school, Asian-Americans had a tendency to hang out in cliques. I did my best to meet people from different backgrounds, but many of my closest friends were South Asian. Maybe we understood each other in a cultural sense on a subconscious level. Or maybe I felt I wouldn’t be judged as heavily or in an ethnic context.

Teenagers will search for any reason to tear each other down. My older brother never seemed as affected as I did in the role of a mixed-race teenager. He had friends from all backgrounds, was a skilled basketball player and often acted unaware of his own heritage. I admired his attitude of complete disinterest in his own self-identity.

I went to college, where open-mindedness appeared more common. I joined a band, straightened my hair, plucked my eyebrows and distanced myself from my Indian heritage to chase an identity I deemed that of a cool, normal American teenager.

My parents, always supportive, never made me feel ashamed for my multiple identity crises. My dad never imposed his Indian culture on my brother and me, partly because he knew marrying my mother was rebellious and nontraditional for his time. He’d be a hypocrite if he led us away from a Westernized life.

I reached a point in college where I would get asked about the origin of my name and tell people my parents were hippies who were infatuated with Indian culture like everyone else in the late 1960s and ’70s.

But in fact, my response came from a fear of being judged.

My father immigrated to the U.S. in the 1970s to further his education. He wasn’t a hippie at all. He was an intelligent, hard-working young man who played cricket and ping-pong in his leisure time. My mother was also a hard-working young woman from a working-class Puerto Rican/Italian family in the Bronx. They met on a blind date and soon fell in love. I can only imagine the hardships of being in an interracial relationship nearly 40 years ago, but they weren’t bothered by their differences. They enlightened one another.

As I physically matured, I began to look more like my father. My eyebrows got thicker, my hair grew curlier and covered more of my body.

But I continued to ignore the Indian side of my life as I became an adult. I rarely attended pujas (prayer events), weddings or family functions. I dated only “white” girls. But eventually, I couldn’t escape being viewed as an Indian-American. I felt frustrated with this longing of wanting to be viewed as an average American male ― like the ones I saw in the movies. The only representation of Indian-Americans in Hollywood at the time were Kunal Nayyar on “The Big Bang Theory” or Kal Penn, and they didn’t look like me either.

My current girlfriend, who is a white American, always expressed curiosity about my Indian culture and routinely asked me questions I couldn’t answer. I realized I needed to dig deeper and ask my father more questions about my heritage. After all, he wouldn’t be around forever and I had never shown much curiosity about his journey.

As I approached 30 years old, my girlfriend persisted, and her interest rubbed off on me. I found us visiting an Indian grocery store called Patel Brothers to pick up ingredients for an egg curry recipe she wanted to try. When I was invited to a Gujarati friend’s wedding, I took her along. I began to see the cultural beauty through her eyes.

I’ve gotten better about asking my father questions about our family and his upbringing in Mumbai. He happily shares stories of his childhood, his motherland and the richness of our shared culture. I learned about his days as a national ping-pong champion and his college years as a cricket player in London. I’ve begun feeling proud of my roots for the first time in my life, and I hate that it took me this long.

My girlfriend is now expressing a strong desire to visit India, and it’s something I want to do, especially while my father is alive and healthy. But there’s something inside still holding me back. Maybe I’m afraid of how I’ll be perceived as an incomplete Indian or a Westernized byproduct. But the more questions I ask and the more I actively participate in learning about and claiming this half of my culture, I feel my insecurities slowly shedding.

It gives me hope that someday I will feel completely confident being exactly who I am: a combination of the many cultures, experiences and stories that have come before me and that I have encountered myself and continue to learn about and live in my own life.

Have a compelling first-person story you want to share? Send your story description to pitch@huffpost.com.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.