Tony Nominees Roundtable: Sara Bareilles, Jessica Chastain, Victoria Clark, Josh Groban, Corey Hawkins and Ben Platt on Broadway, COVID’s Legacy and the Writers Strike

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Ahead of the 76th Tony Awards, which will be held at the United Palace in New York City on June 11, The Hollywood Reporter gathered six of the 2022-23 Broadway season’s most distinguished acting nominees at PMC’s Manhattan headquarters for our annual Tony Nominees Roundtable.

This year, in addition to discussing the challenges and rewards of working on the Great White Way generally and in their nominated parts specifically, we delved into the ways in which the writers strike is impacting the Tonys, whether the theater community should demand a more humane schedule of performances, what audience members do that drives them mad, and much more.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

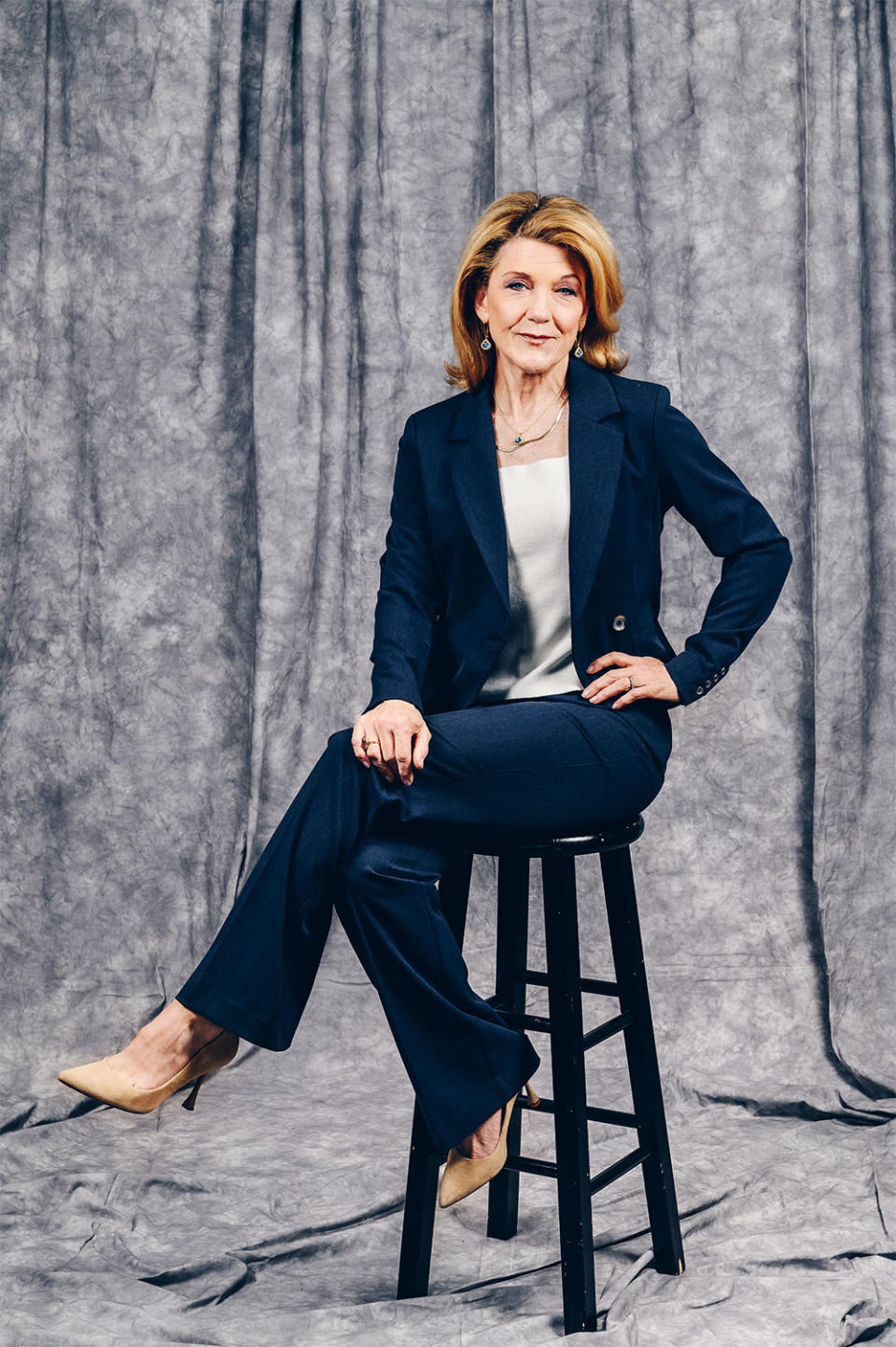

Two of the participants — the most senior and the most junior — already have a Tony on their mantelpiece: Victoria Clark, 63, a best actress in a musical nominee for Kimberly Akimbo, was nominated on four prior occasions as well, winning best actress in a musical in 2005 for The Light in the Piazza; and Ben Platt, 29, a best actor in a musical nominee for Parade, was nominated once before, and won, in 2017, for Dear Evan Hansen.

Three others have previously been nominated but have not yet won: Sara Bareilles, 43, a best actress in a musical nominee for Into the Woods (her two prior noms came in the original score category); Josh Groban, 42, a best actor in a musical nominee for Sweeney Todd; and Corey Hawkins, 34, a best actor in a play nominee for Topdog/Underdog.

And then there’s Jessica Chastain, 46, a best actress in a play nominee for A Doll’s House, who is up for a Tony for the first time.

With a combined 27 Broadway productions — not to mention an Oscar, two Grammys and six Emmy nominations — between them, it will not come as a surprise that the group had a lot of smart insights, provocative ideas and mutual admiration.

You can listen to or read the entire conversation below.

Let’s go around the horn and talk about how you came to these roles. Victoria, you’ve done many different kinds of amazing things over decades in the theater, but I can’t imagine you’ve ever faced a challenge like originating the role of Kim in the musical version of Kimberly Akimbo, which was originally a play. At 63, you play a 16-year-old with an affliction that causes her to age four times as fast as usual. Was that an intimidating assignment?

CLARK It was incredibly intimidating, but I love the challenge of it, and I love being able to revert back to the joy and the physical spontaneity of being a teenager again — that, to me, was the most appealing part about the role. It’s the biggest role I’ve ever done — I barely leave the stage — so that was also intimidating. It’s sort of like if 20 years from now, someone went to Tom Brady and said, “Hey, we’ve got this great idea. Would you quarterback this team, but instead of one game a week, you do eight? And instead of half a year, your season is going to be 52 weeks?” That was the proposal, so I did pause for a while, just thinking about the physical and emotional exertion of this particular role. You didn’t mention that this particular fictitious disease comes with a life expectancy of 16, and she turns 16 in the show, so she knows she’s facing her last days. So it’s been a wonderful joy slash challenge slash emotional journey to confront both the hilarity and the absurdity of that situation, which David Lindsay-Abaire and Jeanine Tesori have set up so brilliantly, while also confronting the mortality issue.

Is it correct that prior to this project you were actually considering hanging it up, in terms of your musical theater career?

CLARK I had hung it up. Way up. I mean, I was doing film and television, and really enjoying that. But doing what we do [in theater] is so athletic. We’re really elite athletes, I’m just going to put it out there and say that. I mean, we want to make it look easy so that anybody in the audience thinks they can just jump up onstage and be right next to us — that is the art of what we do — but it is so gruelingly difficult and athletic. That’s what I think most people don’t know, is how hard we work.

And you had some doubts about whether or not you still were up for it?

CLARK Yes. Also, many of our houses on Broadway were built as vaudeville houses. They’re not accessible. There are no elevators in our theater. We go up and down those stairs. (All the performers laugh.) I mean, we’re all laughing because we know what that’s like. In order for me to go to the bathroom, which I have one opportunity to do the entire show, I’m jogging up two flights of stairs and racing back down. It’s a joyful enterprise, but if I didn’t have a team of people offstage pushing me onstage, I don’t know if I would actually make it out there. And the supporting cast and all of our colleagues onstage, we rely on each other. If we’re having a down day, we just have to look in the eyes of our scene partners and pray that they’ll carry us through.

Ben, in Dear Evan Hansen you played someone caught up in a web of his own lies. In Parade, you play someone caught up in a web of lies told by everyone around him except his wife. Parade was first mounted on Broadway in 1998 and wasn’t a hit at the time, but it’s been on the bucket list for a long time. Why?

PLATT Well, I’m a musical theater nerd, as many people at this table are, and Parade is a piece that’s been a hidden gem and a little piece of art that we all really cherish. You hear it all the time. There’s been productions now and then on a lesser scale; everyone sings it for auditions and showcases and pieces; and it’s just a really beautiful piece of writing. In ’98, there were people that recognized how special it was, but it didn’t necessarily fall on ears that were completely ready to receive it and hear it. I love Jason Robert Brown, the composer, very much, and always did growing up — listened to his music — and as a Jewish person especially, this story certainly was in the zeitgeist of my family.

For any that don’t know, it’s a true story, set in 1913, about this man, Leo Frank, who was a Jew from Brooklyn who moved to Georgia and was wrongfully accused of a murder, and thanks to a trial marred by a lot of antisemitism, was wrongfully convicted. During the two years that he spent in prison, there was a lot of resistance from the North and from other people to try to get him freed. There was a lot of momentum for that, with the help of his wife, Lucille Frank. And just as his sentence was going to be commuted and he was moved to a lesser facility and things were moving in the right direction, he was sprung from his cell by an antisemitic mob and was lynched.

You might hear that and think, “What a great musical!” (Laughs.) But I think, for me, my favorite pieces are things that try to take on challenging material. I feel like the magic of musical theater is that you get to see the inside of people’s souls and hear levels and details in them that you can’t in any other form, and Leo was exactly the kind of character that I wanted to hear from in that way, particularly because he’s become this symbol, martyr, larger-than-life idea, more so than a man. And so, given the way that Jason and the book writer, Alfred Uhry, made him into a person, he was always on my list, as you said, of characters I’d love to play. And when Michael Arden pitched me the idea — he’s such a brilliant director — I was like, “This is the perfect place with the perfect person.”

Sadly, 25 years after the original production and further removed from the events being depicted, it actually feels more relevant. To that point, can you share who greeted you guys on the night of your first preview?

PLATT We had some neo-Nazi protestors outside telling our audience members and patrons who were on their way in that Leo Frank is a pedophile, “You’re glorifying a murderer,” and a lot of tropes that you hear all the time from neo-Nazi groups in regard to antisemitism, and that we’re also hearing for any scapegoated group, like the trans community. It was just a really urgent reminder of why we’re doing this right now. And there’s been all kinds of universe reminders along the way that this is the moment for this particular piece. I feel like antisemitism is kind of an undercurrent that’s always there, and it happens to be coming into the light at this current moment.

And so it’s nice to be telling a story where there’s such an urgent reason. Obviously, any piece of art is worth telling whether or not there’s a great political tie, and so the embarrassment of riches is to have a piece like Parade, where you really believe in it as a piece of art and, regardless of what it’s about, it’s so well crafted and there’s so much to mine as an actor. And then on top of that, as Victoria was saying, when there are down days where you just can’t imagine getting out there, there’s a tangible, real, urgent reason to push yourself out onto the stage.

Corey, it had been five years since Six Degrees of Separation when you came back to Broadway in Topdog/Underdog, a revival of Suzan-Lori Parks’ 2001 Pulitzer winner, which has since been chosen by The New York Times as the greatest play since Angels in America. Was it material that you had long been familiar with? We should note that you played Link, as in Lincoln, one of two brothers, the other Booth or, as he now wants to be called, “Three Card.”

HAWKINS Well, the appeal was definitely Suzan-Lori Parks. I mean, because the play’s the thing. If it ain’t on the page, it ain’t on the stage, as they say. But also to be able to work with [Tony-winning director] Kenny Leon. I had been bugging him, blowing his phone up, like, “Bro, we have to work together!” And then Yahya [Abdul-Mateen II, the Emmy-winning actor] was on board already. I thought Yahya was going to be playing the older brother because he’s a couple years older than me, but then he was like, “No, I’m playing Booth.” And I was like, “Oh, OK. So I guess I’m playing Link,” which was a challenge in and of itself. But it was a joy to be able to bring this play back to Broadway.

I knew of it, and I remember at Juilliard they had done a production of it, and I remember being just enamored with this piece. Suzan-Lori Parks wrote an ode to Black men and allowed us to be our full, beautifully complicated selves. It’s a piece of poetry, and it really does Three-card Monte — it plays this trick with the audience and sort of lulls them into this false sense of security, and then it pulls the rug out from under them at the end.

And do you think there’s something that it says in 2023 that maybe wasn’t even there in 2001?

HAWKINS I think it’s always there. That idea of living in this skin and walking in this world — as a Black man, it doesn’t change and it hasn’t changed, the challenges. Lincoln has to leave every day, go down to an arcade, sit there, put on whiteface, and be shot in an arcade by children. It’s interesting the mental challenges he has to jump through to live his life outside, to make a living. And then he comes home, and it’s great to watch these brothers in this castle that they create, and watch them wrestle and play. And so, I don’t know that it’s changed. I think those challenges are still there.

Sara, you first crossed most people’s radar with non-theatrical singing and songwriting. But your evolution since then, to the extent that you are now nominated for acting, has been really interesting. You wrote the music and lyrics for the Broadway musical Waitress, with Jessie Mueller in the leading role of a baker. Then Jessie steps out and you stepped in to keep the show going. And then you were the driving force behind this revival of Into the Woods, which was a show you were apparently interested in acting in even before Waitress, playing the baker’s wife. What’s the root of your attraction to Into the Woods?

BAREILLES Baking. (Laughs.) It’s really just about the pie. No, I think, like many people, I got exposed to the PBS Great Performances Into the Woods very early on — actually back when I auditioned for The Mickey Mouse Club and didn’t make it. My vocal coach sat me down to prep me for my audition, and she played Into the Woods as a part of getting into the psychology of performance and what is captivating onstage and trying to make those connections for me. I was 12 years old at the time. But when I moved to New York 10 years ago, I was pursuing theater, I thought as a performer, and I got an audition for the production of Into the Woods that was in [Central] Park. I auditioned to play Cinderella and — can I say “shit the bed” on here? The audition was so deeply humbling and so pathetically terrible. I was like, “Oh, I am not prepared to engage in this world in any way.” My music background had not prepared me for the rigor and necessary preparation. It just gave me a lot of appreciation for that. Jessie Mueller got that role — she well deserved it and was wonderful in it — and then, yes, full circle moment, maybe four years later, after writing the music and lyrics for Waitress, Jessie was our first choice to take over the lead for that. It’s been a wild ride to get here, and I’m very grateful for it.

This 2022 Broadway revival of Into the Woods, which proved to be an absolute blockbuster, was never really planned, right? You thought you were going to be in the show for just two weeks for City Center’s Encores! series, right?

BAREILLES I loved the idea of a short stint because, after having been on Broadway and experienced what Victoria was talking about, I was planning on writing a record last year. My life was going to look very different. But as it does, the art wants what it wants, and it bloomed in this really beautiful and unexpected way. I can’t tell you how shocking and delightful it is to be amongst all of you, and to be a Tony nominee for performance means the world. It’s just beyond.

Well, we are going to stay on the topic of Sondheim-related stuff with Josh as we discuss Sweeney Todd, which was first performed in 1979. Josh, you, like Sara, first crossed our radar with non-theatrical singing — well, it may have been theatrical, but not in the theater.

GROBAN I’ve always been hammy.

But then you made your Broadway debut in what might be my favorite theater-going experience ever, Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of 1812. You got a Tony nomination for that show, which was essentially new. Now you’ve come back in a show that has such a history and legacy, and that’s been on your radar since you were a kid, right?

GROBAN It was a part that I loved ever since I was a kid. I didn’t necessarily always think that I would be right to do it. It was just something that I loved to listen to, and I loved to see brilliant performances of it. Whenever you get to hold the torch for a moment for a show that we’ve loved for 40 years, you have a responsibility to not mess it up, and you have an equal responsibility to add what you can add to it — you’ve got to honor it in both ways. We did a roundtable discussion with some previous Sweeneys, and Len Cariou was there, and we were all just kind of marveling at the idea that Len is the only Sweeney that never heard another Sweeney before playing him, and what that must have been like. But I’ve always been excited by the idea of stepping into something like that. Of course, Great Comet was a different challenge, something that’s very new, so you wanted to try and figure out the puzzle of presenting something that is a fresh listen for most audiences.

With something like Sweeney Todd, it’s easy to be a little cynical going into it — “Oh, we’re going to be doing it for people who’ve seen it 10 times.” But we’ve been pleasantly surprised that there have been a lot of people who’ve been gasping and crying at moments where you think, “Oh, that’s a first-timer. Whoa. Interesting.” So we all feel privileged to be able to present this masterpiece every night. We’ve all loved it for a really long time. We’re all terrified in all the best possible ways.

After I did Great Comet, we talked about the athleticism. I was like, “I want to do Noises Off next. I want to do something comedic.” Not that that’s not athletic, but after the drama of Great Comet, I just wanted slapstick. And then the Sweeney Todd opportunity came about and I said, “Oh, putting on the helmet. Going back in. Just when I thought I was out …”

You knew Stephen Sondheim before this project, right?

GROBAN Yeah. I feel very fortunate that some of those concerts that you mentioned, prior to my time in the theater landscape, were concerts for things like his birthday. I’ve always sung his songs, and got to know him a little bit through that. I didn’t really get to know him until Great Comet, when I got a letter to the stage door. He was always an avid letter writer, and I got one of his letters — he’d heard something and wanted to come to the show — and we became pals since then. And we were all really excited by his excitement for our revival. We knew that we had his enthusiastic support of all of us doing it. He passed away two days before our first music rehearsal, so we don’t get to speed-dial and ask him things, but he is now in that echelon of those greats where you just look at the work. You find a part that you didn’t consider and you think, “What did he mean by that?” And you ask through the work of it. We keep finding those answers every day. That’s the fun thing about the repetition of it, is that by show 100, you find a new thing.

I will note, in case there are people listening to or reading this and screaming that I should know this, that we have another Sondheim connection at the table: Victoria Clark’s Broadway debut, in the same theater where she is now doing Kimberly Akimbo, was in Sunday in the Park With George, right?

CLARK So it was. I never went on, so we can’t really say it was my debut. But I was understudying the two Celestes, the little girls who are fishing, and Freida, the German cook, and each of those characters had a second-act counterpart, so I think I had to learn seven roles in 36 hours. The question at the audition was, “Do you read music? And how fast can you learn?” I was a baby then. I had just moved to New York and I was at the NYU musical theater program as a director. The casting people saw me and gave me this audition, saying, “You’re not really a director, you’re an actor. You need to come audition for this.”

Jessica, I think that it’s pretty noteworthy that at maybe the hottest moment of a career that somebody could have — coming off an Oscar, for The Eyes of Tammy Faye, and being in contention for an Emmy, for George & Tammy — you chose to come back to the theater. And it’s not the first time — your first time on Broadway, in 2012, was right after you had the most insane year that anyone has ever had, in 2011, with The Help, The Tree of Life and like five other movies. Some people’s inclination might be, “All right, I better keep my foot on the gas of screen acting, because it’s going where I want it to go,” but yours was to come back to New York. Why?

CHASTAIN Well, I’m a New Yorker. I live in New York. Theater is my first love. And it’s a bit cliché, but it’s the absolute truth: As a child, when I got involved with theater was the first time that I really felt part of something bigger than myself. It was the first time that I felt seen by a community of people, and accepted, and like I belonged somewhere. So for me, it’s hugely important to my upbringing and to the person I am. And so being in that moment of my career where you could choose to do a lot of things, there’s nothing else I really wanted to do but to come back and to do A Doll’s House with Jamie Lloyd and Amy Herzog. It’s so important to me, the idea of women in our society and how we’re valued. So every dot lined up in the way that I really wanted it to.

I believe there had been some discussion, prior to the pandemic, about doing this show with you in London. What changed?

CHASTAIN When I first signed on to do it, I was going to do it at the Playhouse Theater with Jamie Lloyd’s company. We were supposed to start rehearsals in April of 2020, and I was very excited to start. Then the pandemic hit, and I spent a lot of time in New York, just really devastated and walking around Times Square and talking to the people in our community. Live theater really suffered for quite a long time during the pandemic. So I called Jamie up and I said, “I just don’t want to leave my home. Is there any way you would consider doing it in New York?” And he said, “Yes.”

And when he agreed to do it in New York, he said, “Actually, you know what?” We were going to use a different adaptation, but he said, “I’ve really been thinking I would like a woman to look at this play.” And that’s how Amy Herzog came on board. She’s the first woman to adapt A Doll’s House for Broadway, and I find it so exciting because Nora — in our version, in Amy’s version — is complicit in holding up the society that oppresses her, until she’s not. And that is really interesting to me. She’s not just this beautiful victim. She’s participating in the beginning.

All of you except Victoria are nominated for revivals. A Doll’s House has been done on Broadway 13 times going back to 1889. When you’re in a show that has that sort of long and illustrious history, with so many greats having previously played the role you’re now playing, does that make the job extra daunting?

CHASTAIN Well, there’s a great sisterhood. The first time I was on Broadway, I had the opportunity to do The Heiress, and one night I found out that Cherry Jones was in the audience. Of course, her performance in The Heiress is monumental. I was like, ‘Oh, gosh, Cherry Jones is here.’ And I was so embarrassed to do it in front of her. But she came backstage and she had a gift for me. She goes, “I have these books that I want to give you that I used when I was preparing to play Catherine Sloper. Another actress gave them to me.” And she talked about the sisterhood and that we’re all connected and we’re all walking on these paths that others have forged. It was such a lesson in honoring the people who have come before you and not seeing it as something that’s overly intimidating. I see it as — we’re helping each other along the path and maybe discovering new things as we go.

It’s interesting that for all six of you, your principal co-star is also Tony-nominated. For Sara, that’s Brian d’Arcy James as the Baker. For Corey, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II as Booth. For Jessica, Arian Moayed as Torvald. For Josh, Annaleigh Ashford as Mrs. Lovett — Annaleigh just won the Drama League Award, a major honor. For Ben, Micaela Diamond as Lucille Frank, Leo’s wife. And for Victoria, Justin Cooley as Kim’s friend/crush. Obviously, these are all ensemble shows, but can we talk about things that you will remember most or take away most from working with these particular co-stars?

CHASTAIN Well, I love working with Arian. He has a wonderful way of being in the industry and being in the world where he looks at an artist as a citizen — what are you contributing to society, and how are you using your art to become a good citizen? It’s a beautiful thing to have someone dedicating their life to that. It’s also wonderful to get to act in a play like A Doll’s House with him because he’s Iranian, and we talked a lot about what’s happening over there. He has so many people that come to see it, and they say, “This is Iran right now.” I mean, it’s all over the world right now, this idea of women fighting for their place in society.

Were you able to extract any Succession spoilers from Arian?

CHASTAIN Well, I’m also really good friends with Jeremy Strong, and Brian Cox came to our show, so I’m surrounded by the Succession folks. But I don’t want to know ahead of time. I hate getting spoilers.

Sara, Brian is one of the greats. I just saw him in the new musical version of Days of Wine and Roses with Kelli O’Hara. But I believe you had a different Baker at City Center.

BAREILLES I did. Neil Patrick Harris was my Baker at City Center. And to be honest, I was very nervous about the transfer to Broadway because the alchemy of our company at City Center, it just felt like we happened upon lightning in a bottle. I took a minute to say yes because I was asking myself, “Is this greedy? Are we being greedy just because it was popular? Are we trying to extract more? Or can we just let something be beautiful and ephemeral?” Which is what I love about theater anyway. But ultimately I came back to the profundity of this piece and how healing it seemed to be to the audience — I know it was for us inside of it — so it felt like an exciting new chapter to get to tell the story again.

Brian is the most generous, grounded, loving, hilarious man. He is iconic for a reason in this industry. He’s the easiest person to work with. He’s so fucking funny. And it was really easy to find new colors to the relationship of the Baker and his wife, who I named Rebecca, because I’m like, “She’s not going to just be ‘the Baker’s wife.'” But yeah, he just was so generous and malleable. It’s the challenge of discovering the same relationship with a new person and just wanting to be really present. But it was so much fun to work with him. I would do it forever. He’s the best.

Ben, Micaela Diamond was 20 when you guys first started developing these roles together. She’s now 23. And I think her only other Broadway credit is playing Cher in The Cher Show.

PLATT Cher and Lucille Frank, no range at all! Yeah, she’s extraordinary. Leo and Lucile were 23 and 29 when Leo was arrested, and that’s our ages now. I knew she was going to be extraordinary — I had seen her as Cher; I had heard a lot of intel about her; I watched YouTube videos of her singing; and we also went to the same youth theater program here in the city at different times, called Kidz Theater. I saw her play Victoria’s role in Light in the Piazza when she was 15 years old!

CLARK My gosh, I want to see that!

PLATT Let me tell you, it was really incredible — I mean, you’re an icon, but it was pretty great. And so, I knew that artistically I would feel very sort of equaled and challenged. But we just have really connected in a profound way. We’re both cut very much from the same cloth, in terms of being musical theater babies and also Jewish kids who had similar upbringings. We have a similar love and reverence for this particular show and for Jason. And I think that the marriage within Parade is where a lot of the joy and compassion and love comes from.

For us, as wonderful as our company is, the experience of the show is very much everybody against the two of us, so we are kind of on an island receiving a lot of oppression and isolation. So it’s got to be someone that you trust deeply and who you can find joy with within the little cracks where it’s afforded. And it couldn’t be easier to find those things with Micaela. Falling in love with her every night and having the journey of these two people seeing each other for the first time is what makes it bearable and makes me excited to do it. Not that I’m not excited conceptually by the importance of it and the difficulty of it, but as a human being going and doing it eight times a week, the thing I really look forward to is the joy Micaela and I find in each other. I really have never felt so completely held, which is why I think we’re both able to do the work that we’re doing.

Corey, your show built to an explosive situation between your character and Yahya’s — after which, during the bows, you and he would always shake hands. Why was it important to you two to do that?

HAWKINS First of all, thank you for asking about our co-stars because none of us would be able to do what we’re doing or be here without them. Yes, at the end, during our bows, we just needed to make sure that we touched each other, whether it was a hug or a hand on the shoulder or whatever, because we were in such emotional, fragile places that I’ve never in my career had the opportunity — or maybe the guts — to go to. And I thank him for allowing me that.

When we talk about this play, Yahya and I, everyone’s like, “How did you guys bond? How did you become brothers?” We were like, “We’re both artists.” And we knew from the jump the responsibility that we had to come in and speak these words every single night. We also knew what the journey was, but getting there was a surprise every single night. People would come back three times and then stand at the stage door and ask us questions, and we’d be like, “That’s interesting. We’re going to play with that next. We’ll see what we can find.”

But I equate it to running with stallions. There’s this thing where horses, when they’re running and see another horse right beside them, push a little bit further. This play is called Topdog/Underdog for a reason. And so there was a very healthy competitiveness with me and Yahya because it was throughout the play.

To get up and do what everybody here is doing, sometimes twice a day, three-hour shows, it takes a lot. And so you depend heavily on your partner and your co-star. And I was just really fortunate to have him as a brother, because Topdog took a lot.

Victoria, Justin is just 19 and had never been on Broadway before.

CLARK This is his professional debut. Actually, his professional debut was at the Atlantic doing this role. He came to the casting director’s attention through the Jimmy Awards [which recognize high school acting], which were on Zoom because of the pandemic. So no one had ever seen him in person.

PLATT What?!

CLARK Right? The Jimmy Awards have become this great fertile ground for finding young actors. Justin and I met on the first day of rehearsal for the Atlantic, and we had an instant bond. It was one of those things where it was just an instant connection. Of course, I felt very maternal toward him — I’m 44 years older than he is — and yet we have to meet eye to eye as colleagues. So for me, it was such, and is such, a beautiful experience to learn from him every night because he doesn’t have any hangups. He has no formal training.

HAWKINS Fresh eyes.

CLARK He has fresh eyes, he’s very alert and responsive and grounded and beautiful. And it’s so moving to do this piece with him, which is essentially about this young girl facing the end of her life — for me to look at his face and not see too much life on his face yet, it’s beautiful. Even in the past year and a half that I’ve known him, the mom in me can’t help but notice how those features are maturing into a young man. When I met him, he felt like a baby.

He had 20 minutes of insecurity on the first day. I’m quite silly in rehearsal, and this show really brings it out of me. We were improvising something, and he wasn’t really sure what I was doing. He has a candy stand at the skating rink, and I was like handing him tortilla chips for my bag and just making up all this stuff, and he was just frozen, like, “What am I supposed to do?” He kind of whispered to me, “What are you doing? What are you doing?” And then we talked during the next break and he kind of had a moment, and then that was it.

Josh, your scenes with Annaleigh are hilarious. She is always so good, but I don’t think she has ever been better than in the scenes of physical comedy with you in this show.

GROBAN I was first able to bear witness to her incredible physical comedy and how she’s able to turn a phrase and communicate in A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Shakespeare in the Park. I watched her completely transcend up there and thought to myself, “Gosh, I would do anything to bounce off that one day, to be able to just be and play in that space with her one day.”

We both have very big shoes to fill and wanted to make it our own and have fun. She’s brought so much of her own instincts to this role in a way that has been incredible to just watch in rehearsal. It’s hilarious. Sondheim, we knew, wanted Lovett to be hilarious, to take the wind out of moments in the show. And she makes Sweeney funnier.

The other thing that Annaleigh really wanted to do was to develop more of a sexual chemistry and a romantic chemistry between Lovett and Sweeney that hasn’t always been there. It’s always been about their goals in life — they’re on two different boats that are next to each other — and she really wanted to make sure that there was that connection, that there was actually a reason to believe that beyond their own goals, that behind the scenes, there was more going on there, which would make the breaking of trust even more heartbreaking.

There’s one hilarious scene where she’s basically —

GROBAN There’s some twerking going on. She’s got the hots for Sweeney, for sure. And their definition of love and want is very different. They do have very different goals. But because there is such a give and take that she’s brought to that role, there’s so much more to play off of. And bouncing off of the stuff that she brings and keeping it fresh every night has been such a joy for me. It’s amazing to have a partner that you can trust like that.

I’ve got to ask about some of the oddities and eccentricities of these productions. Jessica and Ben, you guys are onstage alone for extended periods of time when actors usually are not — Jessica while the audience is entering the theater, Ben during the entire intermission. Why is that? And what do those moments add to your performances?

PLATT Well, from what I gather, they’re quite different — I haven’t been able to see Jessica because they started when we were already started. But Michael Arden, our director, came to me with this concept way at the beginning when he pitched me the whole production back in 2018. It’s definitely his idea, not mine. But in terms of what it means for the production, Leo is convicted at the very end of the first act, and in the midst of this kind of cacophony of celebration, a very ugly celebration, he’s put up in his cell and changed into his prison clothing and then sat in his cell and remains there for the intermission. I think there’s something very confronting and kind of uncomfortable about it in the sense that this story isn’t something that particularly Jewish people or really anyone has the luxury of disengaging from entirely. Intermission is such a comfort when you get to completely disengage and go have a drink and go to the bathroom and kind of forget for a moment and catch your breath — not that there aren’t plenty of people who do that, which is a super valid reaction to the lights coming up and it being intermission. But Michael really wanted to challenge that impulse and confront the audience with the fact that there was no escaping for Leo — he spent these two years in isolation — and so for me, it’s very much about honoring that fact. The show is super propulsive and we’re trying to cover a lot of ground and express a lot of ideas and big thoughts, and there isn’t a ton of time to just dwell with the fact that this three-dimensional man spent the last few years of his life sitting alone in a room for something he didn’t do. So it allows me to have this ritual. No matter what other noise is happening in this award season or on any given day, or if I’m hungry or I’m sad, or whatever it might be, there’s a point in every day to just sit with that fact and pay homage to that fact. I’m curious about Jessica’s experience, because for me it’s entirely different every time, both in terms of where I’m at and where the reactions of others are.

What if you need a bathroom break or a glass of water? What if people are being assholes in the audience? You know, “Hey, Ben!”

PLATT We certainly get that. I think the whole point is to see the variety of reaction. There are people that sit and just take it in entirely and don’t move. There are people that completely disengage and go pee and have snacks, which is also totally valid. There’s reactions I don’t love, which is people taking videos and photos and saying, “Turn around, Ben, I love you!” But it comes with the territory. That’s the point. If it was a perfect sea of people sitting and paying respect, there would be no reason for the conceit.

Jessica, I know you get a little bit of the weird behavior, as well. This is as people are showing up.

CHASTAIN In ours, it’s welcomed though, in a weird way. In the beginning I didn’t understand how Jamie wanted to direct this — he just kept saying he wanted it to be relentless on me, and he wanted me to be trapped most of the time. And a lot of the show — the majority of the show — I can’t turn away from the audience, so the audience has full access to me. The preshow is when people are coming in with their drinks or whatever, they see me, I’m sitting in a chair, kind of just going in a circle, and in some sense it’s like treating me as an object to be observed.

We said in the beginning, “Well, there’s going to be people filming. There’s going to be people taking pictures of me.” The whole idea of someone coming into the play because they saw Zero Dark Thirty or they saw The Help, and bringing the history of that baggage with them, of the other performances and of celebrity culture — what the preshow does is it allows that to happen and then get dissipated. So they come in, they take their pictures — there’s so many times I see people taking selfies with me. They make eye contact. They say, “Jessica, I love you!” There’s very sweet things, they send me hearts and all this. And I stay in character. And I make eye contact. That’s the thing. I make eye contact with every single person in the audience.

Do you recognize people?

CHASTAIN Oh my God, Bono came. I thought I was going to die. That was so stressful. Al Pacino. I’m literally making eye contact with people. Like, glancing over. Sometimes I’ll hold it longer if I feel like I’m being challenged in some way. But it creates this sacred space in the theater. I think people are used to going to the theater and being like, “OK, I can see the actors, but they can’t see me.” And I say, “No, no, no. I see each and every one of you. We’re doing this together.” And there’s a couple of times in our show where my character, Nora, is confronting the outside world in some sense. At the beginning of the show and the end of the show, the audience is supposed to go on that journey with me. And so I feel very closely connected to them in every performance because of it.

I guess it also gets rid of something that a lot of actors tell me they don’t like, which is entrance applause.

CHASTAIN Yeah, sometimes there’ll be like a couple people that’ll applaud when I’m rotating before the show starts. You’re thinking, “That’s a bit awkward.” Slowly, everyone in the ensemble starts to come in with their backs toward me. It gets the audience ready. When the show starts, there’s no applause. We never have anyone filming. No one’s taking pictures. It’s like all of a sudden, the tone has been set. I think it was really wonderful of Jamie.

GROBAN My first line, you can’t hear it. It’s annoying.

CHASTAIN It takes you out of character, doesn’t it?

PLATT It does.

CHASTAIN You work so hard to be in character, then you come onstage and you’re like, “Oh yeah, I’m also someone else.”

GROBAN I’m pulled out of the pits of hell to tell the tale, and I see a lady with my Christmas album T-shirt. “Just you wait. You’re in for a treat.”

Josh, the throat-cutting and body dispatching in your show is very impressive. Can you break down how it happens?

GROBAN When I was talking with our director, Tommy Kail, and Mimi Lien, our extraordinary set designer, we really didn’t want to be “conceptual” with the violence of the show. We wanted it to be really there and in people’s face, and we wanted it to be bloody. There’s a great kind of dark, twisted humor when the body just kind of drops while singing, “Goodbye. Goodbye, Joanna. You’re gone.” And the body’s going. And people laugh. That’s what Sondheim wanted. It’s that dark, twisted kind of thing. The magic trick of that is really important, that we have that stuff working, so we’re constantly fine-tuning things. That chair is like an old antique Chevy. It’s really heavy, clunky and there’s a clutch. It was really fun to figure out how to use all that stuff and fun to do all the special effects. It’s not great for the costume department. Ironically, the only way to get the fake blood out of our skin is with shaving cream.

Did I hear that there were a few performances at which you encountered technical difficulties?

GROBAN During previews, we had a couple of nights where the chair just decided to malfunction. So I’m just up there by myself with that device. The other actors’ safety is my responsibility — when I turn the chair and the trap door opens, I have to see that it’s open all the way, I have to see that the padding’s in place, and there’s a lot of things I have to see before I send them down. So if the slope doesn’t open all the way, if something’s not exactly right, I have to jump into plan B or C mode, which is complicated when you’re already doing a lot.

There was one night when the chair decided to not come back up from the flat position. Judge Turpin, Jamie Jackson, is supposed to walk in and, of course, nothing is supposed to seem out of line — he doesn’t know he’s going to die. Sorry, spoiler alert. And he goes up, and he looks at it, and he looks at me, and we’re just going, “We’re just going to do this. All right.” And he kind of sits on it, half leaning back, like, “This is fine. There’s nothing to see here. There’s just been some unintentional comedy.” We’ve had dead bodies have to just walk off the stage at times, in a very Play That Goes Wrong kind of way. That’s what previews are for!

Victoria, you’re playing a girl of 15, 16 years old. I assume she’s not going to sing like Victoria Clark, with years of skill and experience. Do you alter the way you sing to play her?

CLARK Absolutely. I could talk for a long time about this, sitting here with three really brilliant singers [Bareilles, Groban and Platt], and you guys [Chastain and Hawkins] probably sing too. But yes, that was a big part of the development of this character: How does she sing, and how can I craft this so that the speaking voice matches up with the singing? Technically, I would say that when I’m singing full into my legit soprano voice, it kind of feels like I’m on a four-lane highway in L.A., let’s say. And so to get mentally and technically where I need to be, I have to bring it down to one lane — a twisty country road, let’s say — so that I’m still on my breath and the cords are phonating healthfully, but it’s not with as much muscle. And that, ironically, is very tiring, because it’s not what I would call the easiest sound for me to make with all of my legit and classical training, but it is the most honest sound for Kim. And so that’s been part of the challenge. I’m a big voice nerd. I love talking about this.

Well, you also teach, right?

CLARK I do teach, and I am a devotee of honest singing, so that the singing has to match the moment. If my whole life’s work could be summed up really, it’s making sure that whether I’m speaking or singing, the thought of the sound contains the life experience and the emotion and the honesty of the moment so that it’s almost pre-programmed, in a way. For many of us who are kinetic actors, we don’t tell the body how it’s going to move; we just allow it to. So the goal is to have the voice do exactly what’s required. Nothing more, nothing less, in that moment. And that’s a beautiful challenge. But for this particular role? Yeah. Tall order.

BAREILLES You do it impeccably.

GROBAN I can’t wait off-mic to just pick your brain and talk about voice, because it’s so true.

Well, Sara, I want to ask you, and then Josh, about singing Sondheim music. Sara, you’ve said that there’s something about it — the lyrics or the pacing or something else — that makes it particularly challenging, even for somebody who’s sung as much as you have.

BAREILLES It’s very dense and intellectual, and melodically it’s really rangy. There’s big intervals. Pitch is really important to me. It drives me crazy when I can’t land the note. I worked with Rob Berman, our music director, and we sat singing through these songs, and I was, to be honest, a little surprised. I thought it would be an easier sing. I spoke to my old music director, Nadia DiGiallonardo, who did Waitress with me, and she was like, “This should be no problem. It’s right in your range.” I was like, “It doesn’t sound like it’s in my range.” Definitely, the finale and the opening number I’m singing much more legit, sort of stylistically, than I normally do.

CLARK You sound beautiful up there. I’ve got to say, I love that part of your voice.

Josh, have you found it to be its own kind of unique beast, as well?

GROBAN Yes. It’s a puzzle to keep at the standard with this music that we all want to have with it. Of course, we all knew how complicated the score was when we went into it. The music rehearsals were long, and you hear other versions of it, and then there are notes in there that as you study it more and more, you think, “Oh, that’s supposed to … that’s that, OK … and that’s that.” And the pitch thing is exactly right. It takes just an enormous amount of focus out there. And I think the other thing — such a great combination of the head and the heart that he wrote for this stuff — is that it is really brainy, even though the stories are so weird. I mean, I always joke about the elevator pitches that he might have said when asked what he was writing about next. “Oh, good luck with that, Steve …” But he finds common human threads through weird stories that we all connect to.

Ben, I read that you visited the Leo Frank house in Brooklyn, and others of you have done variations of that sort of research. Corey, was there anything that you were able to do to prep for your show aside from really just studying the material?

HAWKINS Yes. There’s a lot there. We had guys who were teaching me how to actually play the cards—

PLATT It was unbelievable. I have to say, it was crazy. It was really virtuosic. And, I mean, you were doing an incredible amount of things besides cards, too.

HAWKINS Thank you, man. When I play spades with my friends, I always give the cards to someone else to shuffle because I don’t know how to do it — they always fly out of my hands — and we take spades very seriously. And Yahya also was never taught the hype or the trick of it. I think he may have figured it out, but he never knew how I did it each night. So he knew what it was, but he was never able to re-create it. And I remember them telling me that when you don’t have those cards on you, it should feel strange, because it feels strange to those guys — this is their livelihood — and you have to be so good, because some of those guys are going to be coming to see this show. And they did.

BAREILLES They’re going to know.

HAWKINS They know! And the audience can’t get the trick because that’s a big faux pas — you’re not supposed to actually give up Three-card Monte — so they were very secretive about that with me, and I wasn’t allowed to tell anybody in the production. People still make their hustle doing that, so you have to be respectful of that.

I also had to learn how to play the guitar and sing and all of that. It was just a lot of juggling. I’m a big history nerd, and I love jumping into plays because you become a student of these things. You have to go to the house. You have to go and learn the things. And really, it expands who you are as a human and as an artist, so I just love adding those things to the basket.

Each one of you were, at one time or another, on Broadway before the pandemic, and obviously, you’re back now, so I wonder: What are the biggest changes that you’ve noticed? For yourself, for audiences, for Broadway as a community…

PLATT I was thinking about this a lot recently. The pandemic just reminded me of what I already knew, which is that I love live theater so very, very deeply, and I’m so grateful that it exists and that it was one of the only things that was so completely untouched by the pandemic. You can’t touch the experience of watching something live. It’s so sacred.

Not that this didn’t exist already, but I feel like with Parade, there is such a care for the human beings that are in the company before there is a care for them as artists. If anyone asks, “How can we hold any of those conversations together and hold space and sensitivity for all different experiences and affinity groups and types of people?” It’s possible because the experience that I’ve had in this rehearsal room is there’s just so much care and time taken for making sure that we’re all OK and healthy as people before we dive into the work.

When we’re doing this harried crazy thing [of putting on a show], especially City Center things where every moment is costing thousands of dollars, it can get lost and things can get rushed and pushed and it can fall to the wayside in favor of just getting to the finish line. But never was there a difficult piece of imagery, a triggering prop, nothing that came into the space without the time and space to prepare for it, the recognition that it was something difficult and the ability to have a conversation and hold each other first. And I really think that that couldn’t have happened without the kind of world reckoning that has gone on. I’m very encouraged by that moving forward.

GROBAN What this very traumatic couple years we all experienced together gave us, for better or worse, was a whole lot of perspective. And coming back into something that is as wonderful as this community, and doing something that is as irreplaceable as live theater, has given us even more gratitude to be able to get out there and share these stories.

It’s also given us a filter for the other noise that comes with being in this universe, because we’re in a bubble — we’re in a theater every day, and there’s a lot of chatter outside, and there’s a lot of noise, and there’s a lot of other things that can sometimes make their way into the sacredness of where we are. And coming out of that time when we had Zoom, with no connectivity, and all those other things, it’s allowed me, at least, to focus even more on what matters and focus even less on what doesn’t, and to make that space even more sacred than it was in the past.

How about in terms of self-care and self-preservation? Jessica, you got some flak for wearing a mask to the Oscars. Most people didn’t know why you were being so careful.

CHASTAIN We were testing every day on our show, and even if you had no symptoms, if you tested positive for COVID, you were out for a week — and I was meeting people at the stage door who flew in from Shanghai and flew in from all over the world. To be out of the show for a week? It just felt like it was so irresponsible. So I was wearing the mask at the Oscars. I got quite a lot of flak for that. A lot of people thought I was making some political statement. I don’t know what they thought. I’m like literally —

GROBAN Theater people knew. We knew.

CHASTAIN Well, OK, good. I’ll tell you, the best thing is someone at the stage door gave me a mask that said, “I’m On Broadway.” But yeah, the SAG Awards, the Oscars, a lot of people were like, “What are you doing?!” I just couldn’t get sick. And I didn’t. I haven’t missed a show.

How about compositions of audiences? Does the audience, age-wise or in any other way, look different to you, Corey?

HAWKINS Well, it definitely did for us, which I was really grateful for. Also there were students, kids. I was like, “Are you really sure you should be bringing the kids to see this?” But it isn’t anything that they don’t see when they walk out of their doors, especially here in New York. Also, this is a generation of kids who in the past few years were deeply affected — I mean, we all were affected, but students, with school on Zoom and all of that kind of stuff, were deeply affected by the lack of community and lack of interaction. For some of them, it was their first time seeing a show ever, on Broadway, off Broadway, whatever. And so this season, and a bit of last season as well, coming off of COVID and how detrimental it was to a lot of us in terms of mental health, it was great to see them and see this season of shows. It was such a good season.

CLARK It was a robust season, but we’re not where we were. We’re not at the numbers that we were prepandemic, in terms of attendance. I think we’re still looking for the audiences to not be afraid, to come back to the theater. The stories we’re telling now and have told this season are so beautiful and uplifting and enriching. But yeah, that’s the one message I think we really need to get out there, is that if people are hesitating, you don’t need to. There’s only one place to get this particular kind of entertainment, this kind of experience. A lot of people during the pandemic started to rely on other mediums and became very comfortable getting everything they needed from a screen. That is not what we’re doing. This is live human interaction. This is an exchange of energy with an audience that you can only get in live theater, and it’s a seminal human experience.

BAREILLES There’s a lot of research about loneliness being this new epidemic. And I do think that it isn’t just the isolation of the pandemic, but it’s also the dependency on screens — we forget how to be human with each other. It’s so primitive what we’re doing. It’s so analog that we stand on a stage and we tell stories and we sing with our voices or we speak truth. I really believe this is essential soul-giving, soul-saving, life-saving work that happens onstage.

This may seem like a trivial thing to bring up now, but I want to ask you about the Tony Awards. The fact that the Writers Guild has now said that its members will not picket the Tonys, allowing the show to move forward, could really be a lifesaver for a number of shows. You all know what a difference it can make if you can put on your marquee or on your advertisements that a show is Tony-nominated or Tony-winning, not to mention having a show featured on the national broadcast.

BAREILLES I think it’s amazing that we actually get to go through with this. But what it really highlights is that we are too dependent on the Tonys being the only broadcast system for this industry. We have to get more creative about other ways that people can access our beautiful program. There just have to be more tributaries for eyeballs, to be able to know what’s happening so they want to engage.

HAWKINS I also think about the impact regionally, because not everyone has the time or financial ability to get to New York. So when people see these shows or know about these shows, you can bring them and these incredible companies to those towns, as well, and keep people employed.

CLARK I keep thinking about the young Jessicas, Bens, Coreys, Joshes and Saras. Like, did we not all watch the Tonys and aspire to be a part of this community? The future is with those young people. I want those young people to feel like they have access. Even if the Tonys is not widely viewed or whatever, it is by the people who are going to tell the stories in the future. So I think it’s important.

PLATT Some of my very first queer representation I remember seeing and really sinking in was when they showed the nominees with whoever their person is that they’d brought; so many of the theater artists had same-sex people that they were with, their partners there. And even early on, as recently as the late ’90s when I was a kid watching the Tonys, it might not have been as overt as it could be now, but even then, just seeing one of the guys nominated for a musical holding his man’s hand or giving him a kiss when they were saying his name, I remember the visceral impact of little moments like that. So I’m just very grateful that the show gets to go on in any form, for the queer people that are going to be watching, the little queer kids who I know are looking forward to this particular thing and only get it once a year. But I agree that it shouldn’t be just a once-a-year kind of a thing.

CHASTAIN I used to record the Tonys on my VHS player — I don’t know if everyone in this room knows what a VHS player is — and I would watch it throughout the year. I used to get American Theatre magazine, and I dreamed of someday living in New York with my people. I love being onstage, but I also love being in an audience and watching these productions. And I think the beautiful thing about the Tonys is for the people who don’t have a lot of finances to be able to go see the theater. I mean, for me, it created a love of theater. Then I would go to community productions. I’d watch the Tonys, and then we would do a “Best of Broadway Revue” in Sacramento, California. So I think it’s so important to have that outreach to keep live theater accessible to people who can’t afford it.

CLARK I just want to say one more thing. As Corey said earlier, “If it’s not on the page, it’s not on the stage.” We’re only as good as what we’re given to speak and sing. So, of course, we’re all supportive of this strike, and we want them to succeed and be paid what they deserve. We’re all members of multiple unions here. So I feel like it’s gritty and it’s tough what they’re doing, but we are behind them.

CHASTAIN Is anyone here in the WGA?

BAREILLES Yeah. I’m so grateful that this is how it shook out. I don’t blame the WGA. I think that there needs to be a strict sort of protocol, but I do think that there are a lot of playwrights that are TV writers. They can’t make a living being a playwright, so they have to go to other mediums. So I think it ends up inadvertently punishing the wrong community. And it’s a community that really needs eyes on it, for the right reasons, I think. So I’m so thrilled. The night is about celebrating theater as a medium, as a community, as a collection of stories and artists who bring this to life and want to project that into the world. It doesn’t feel like a competition. It really doesn’t. It feels like a celebration, to me. Coming from music, I always was so sort of destabilized by the way music can feel competitive — it’s a scarcity mentality, like there’s not enough for everybody. Because theater has to move and change so much and nothing lives forever — I mean, Phantom is gone, nothing lives forever here — you can’t sustain the delusion that you’re actually in competition with anybody. We’re just celebrating incredible performances.

Josh and Sara, you actually co-hosted the Tonys in 2018.

GROBAN I first reached out to [James] Corden, who hosted it [in 2016], like, “What is your advice? What am I getting myself into?” And he said, “For every other award show, there is that feeling like everybody’s there with their entourages of 50 people and everything. But when you’re in front of those people at the Tonys, every single person in those seats has wanted it since they were 5 years old and they’ve worked their asses off to be there.” And like Sara was saying, there isn’t a competitive feeling. Everybody there is so excited that the night is going to project what we all love about this world to so many people. Everybody’s just supportive of that. And I know that I speak for everybody in this room that we can’t wait to do what we do on that night for the next Sweeney watching, the next Baker’s Wife watching—

CHASTAIN The next Nora.

GROBAN The next Nora, absolutely. Because they’re watching. And they were us.

As somebody who covers all the different award shows, I feel that it is definitely the most entertaining one to watch. You guys are actually doing what you are being recognized for doing!

GROBAN I mean, it is the best award show.

CHASTAIN I remember — because, I mean, VHS — they used to do scenes from plays.

Are you volunteering to do that?

CHASTAIN No.

GROBAN I think that you should bring it back.

HAWKINS I remember Viola Davis doing King Hedley and just being like, “Oh.” You leaned in.

All right, with our last minute, let’s do some rapid fire — please just shout out the first thing that occurs to you. Excluding family, who is the person whose attendance at one of your performances of the show you’re currently nominated for has meant the most to you?

CHASTAIN Liv Ullmann.

CLARK Mary Beth Peil.

HAWKINS Jeffrey Wright.

GROBAN Len Cariou.

BAREILLES Joanna Gleason [the original Baker’s wife].

What is the most unusual thing in your dressing room for this show?

PLATT A neon Jewish star sign. And my walls are pink.

BAREILLES My dog.

CLARK My original rehearsal music from Sunday in the Park with George, framed.

CHASTAIN I have pictures of actresses on my wall — Viola Davis, Liv Ullmann, Isabelle Huppert, Catherine Deneuve and Vanessa Redgrave.

GROBAN I have a Victorian-era penny in my dressing room, from the time period of Sweeney.

HAWKINS I have an old, original print of Grace Jones.

What is the most annoying thing that an audience member did at one of your performances of this show?

CHASTAIN Toward the end of our show, Torvald says to Nora, “Where are you going?” I say, “To take off my costume.” And when I said “to take off my costume,” one woman — I think she probably was deep in the cups — yelled out to Arian, “You take off your costume, buddy!”

Really? You go to A Doll’s House to get drunk?

CHASTAIN To heckle the men.

CLARK Actually, it’s very interesting that the women are heckling the men!

PLATT That’s something to be examined.

CHASTAIN Yeah.

PLATT I mentioned that someone played the entirety of “Thinking Out Loud” by Ed Sheeran in their purse on their phone. Like, at a good volume, a hearable volume. She, I guess, bless her heart, didn’t hear it and just kind of watched the scene attentively. It played for a good full minute.

Did it change the way you approached your character?

PLATT It made me scream a lot more.

HAWKINS I feel like people like that actually know it’s playing, but they don’t want to acknowledge that it was them. Our play is all about the inheritance — you know, that stocking that the brothers are talking about the entire play — and one show, at the very end, it rolled off the stage. Yahya’s character has to give it to me, but it rolled off the stage, and this kid picked it up, and Yahya sort of went over and thought the kid was going to put it back, but the kid was just like, “No, I’m keeping this, this is my souvenir,” so we didn’t get it back, and Yahya had to go and find a piece of paper towel [to stand in for it]. I like the theater.

GROBAN Sweeney is kind of a hard show to sing along to, but people do love the score a lot, and there was a guy that we noticed was very, very largely conducting the whole show in his seat.

CLARK A lot of young people come to see Kimberly Akimbo, sometimes too young. We’ve had mothers holding 3-year-olds! But there was a group that came from Lodi, New Jersey, and that’s a town that’s referenced in the show, and every time we said Lodi, they stood up and screamed. In the second act, things start to spiral downward pretty rapidly. So we were making up ways to say the lines without saying Lodi.

If you could snap your fingers and make it so, what would be the ideal number of performances of your show per week?

GROBAN We’re doing seven and that’s a good number for me. I’m a weirdo who likes being marinated for that second show. I like holing up in my dressing room and playing my Nintendo for three hours and then drinking tea and feeling like I’ve done the show once so I’m not worried about it.

CHASTAIN Mine might not be popular, but I’m happy to do eight shows because I know theater needs it — but I would prefer to do flag shifts of this play, because I’m, like, crying for an hour, so to do that eight times a week feels like a lot. Five different days would be great.

CLARK I think six is a good number. I’m actually trying to talk to the union about this because I’m an equity counselor, and I think we need to move away from eight a week. I really do. It’s too much. I know that it’s the financial formula for now, but I think we need to rethink it. Seven is more humane.

BAREILLES I think six or seven would be a sweet spot. I really think you need a weekend, you need two days off in a row. It’s relatively inhumane to only get one day off; the rest of the world gets two days.

CLARK We need balance with our family.

CHASTAIN Yeah. That is the thing.

HAWKINS I like the idea of eight shows because that’s the thing that sharpens the best of them. That’s why Broadway isn’t easy. But the two shows two times a week is such a task and it’s such an ask. And to have only one day off, and we then also have to work on those days …

CLARK Today is our day off, for everyone listening at home! (Laughs.)

HAWKINS The holiday season is insane.

CHASTAIN Yeah, nine shows a week.

PLATT I like the seven. I mean, I would go back in time and do three Evan Hansens a week, not eight — but I think seven. If it’s a Sophie’s Choice between the two, I would keep the only one day off, but I would chuck the Wednesday matinee so far out to the ocean and never do that again.

Oh, that’s interesting! If you’re an audience member deciding which performance to attend, which is the show that they should put last? What’s the one that you would skip?

CLARK Saturday night. Do not come.

CHASTAIN Oh, I love Saturday night on Broadway!

CLARK I’m burned out. I’m like a crispy piece of bacon.

BAREILLES Avoid Tuesdays. I’m like, “What day is it? Where am I?”

HAWKINS I love a good Friday night.

PLATT A Shabbat show!

BAREILLES I don’t like Fridays. I like Thursdays and I like Saturdays.

CLARK Thursday is payday, everyone.

PLATT That’s true.

HAWKINS But come any night!

GROBAN There’s no wrong show. Every show is consistent and perfect. Come anytime. (Laughs.)

Last one, put it out into the universe: If you could play any role on the stage in the future, which would it be?

HAWKINS It’s Sweeney Todd. I want to sing. I’ve been telling people that I can’t wait to come see Sweeney Todd because I’m obsessed with that show — and also Josh, he’s my guy. But also, Sam Cooke has been such a dream role for me. We’ve been thinking about how to get it to screen, and I’m like, “It might be a good idea to play Sam Cooke on the stage to see what happens with it.” Such a tragic story, but so impactful.

CHASTAIN I have one. Alma from Summer and Smoke. Tennessee Williams said that it was the part that he felt the closest to, and it’s not performed that much, that play. I love it so much.

PLATT George [from Sunday in the Park with George]. Since I was a wee, wee child. Before I leave the Earth, I will do it.

CLARK I would love to do another original show. I like working on new pieces. Anybody out there who’s got one …

GROBAN I so loved working with Dave Malloy on The Great Comet and I’m always fascinated with what he’s going to cook up next. I would say, like Victoria said, something new, something that I could dive into and be the first, like Len did for Sweeney all those years ago.

Nice. Well, on behalf of The Hollywood Reporter and everybody listening or reading, I cannot thank you guys enough for sharing some of your day off with us. And listeners and readers, sadly Into the Woods and Top Dog/Underdog have closed on Broadway — you can see Into the Woods on tour — but there’s still time to see A Doll’s House, Kimberly Akimbo, Parade and Sweeney Todd!

CHASTAIN When do you guys close? I’m closing June 10th.

CLARK Never. We’re never closing. Kimberly Akimbo will run forever!

GROBAN Mid-January for me. I think it will go on, though, after that.

PLATT August 6th. Hard stop.

Get your tickets now, folks! And thanks again.

Interview lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter