Toni Morrison celebrated: She 'opened the door and she turned on the lights'

NEW YORK — Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, a colossal figure in American literature, received a final goodbye from friends and followers Thursday at a celebration of her life at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan.

Morrison died August. 5 at 88.

Morrison's works, often described as incomparable and revolutionary, communicated the pain and prejudice of the black experience, especially that of black women, to millions of readers around the world.

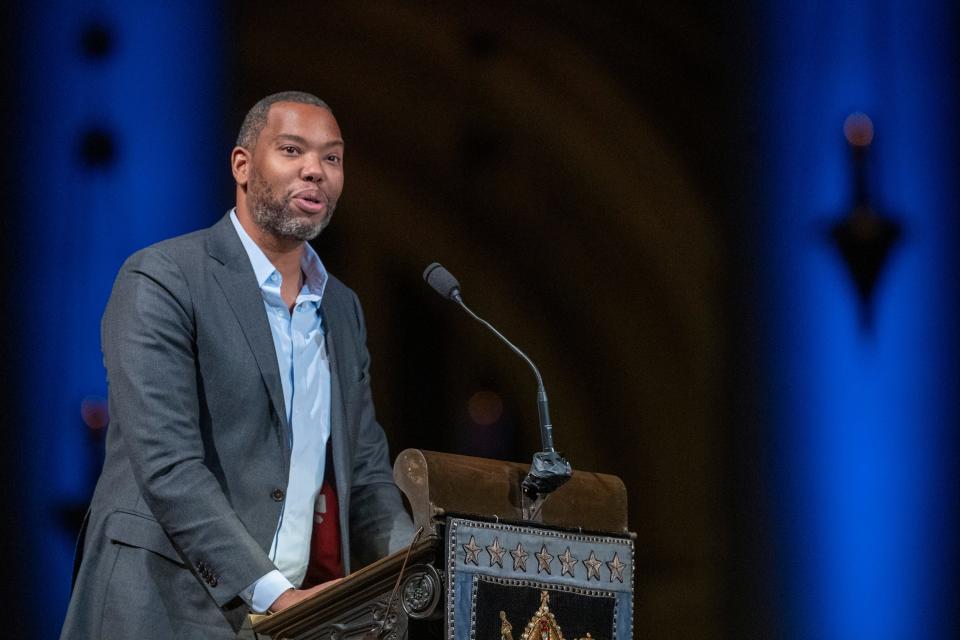

Nine celebrities and literary masters spoke at the memorial, among them Oprah Winfrey, Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Remnick, and author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates.

"The first time I came face to face with Toni Morrison was in Maya Angelou’s backyard, for a gathering of some of the most illustrious black people you’ve ever heard of," Winfrey told a crowd of more than 600, remembering a celebration after Morrison won the Nobel Prize. "My head and my heart were swirling."

Winfrey has chosen more books by Morrison than by any other author for her book club, she said. But Winfrey worried, at first, that Morrison's work was too demanding.

But Morrison gave Winfrey the confidence to choose those books: "'She said, 'That, my dear, is reading,'" Winfrey said.

“There was no distance between Toni Morrison and her words. She believed it was a writer's job to rip the veil off," said Winfrey, who drew the most applause of the evening. "Her words don’t permit the reader to down them quickly and forget them.

"They will not be ignored," she continued. "They can gut you, turn you upside down, make you think you don’t get it. You experience … a kind of emancipation, a liberation, an ascension to another level of understanding."

When the crowd surpassed the cathedral's seating capacity, people clustered by entrances, craning their necks to catch a glimpse of the literary luminaries who spoke. Attendees snapped selfies and photos of the cathedral interior. The guest speakers, led by priests, arrived to rich organ music.

“Great novelists illuminate worlds we dimly know," said Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker magazine. "Great novels either open a door or they turn on the lights. Toni Morrison did it all. She opened the door and she turned on the lights.”

Morrison often began her writing early in the morning but jotted down ideas throughout the day on a yellow notepad she kept close, said Angela Davis, an author, activist and academic who called Morrison her "big sister."

But although Morrison focused constantly on her work, she was always present for her two sons and her friends, Davis added.

Honoring Morrison: Gathering honors author Toni Morrison and her efforts to preserve African-American history

Remembered: Author Toni Morrison, Nobel laureate, remembered for honoring history in Nyack and beyond

One of the greats: Toni Morrison was our greatest writer, and her stories about race our most essential

"She demonstrated a way of being in the world that allowed her to simultaneously inhabit multiple dimensions," Davis said. "She was never only partially paying attention. She was always 100% engaged."

For author and professor Jesmyn Ward, the first woman to win two National Book Awards for fiction, Morrison's unflinching telling of the black experience was a sort of North Star.

"We wandering children heard Toni Morrison’s voice, and she saved us," Ward said. "Something in that absolute narrative presence in her sure voice communicated this: you are worthy to be seen, you are worthy to be heard. Even in your quietest moments, you are worthy of witness."

Poet Kevin Young, who directs the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, said Morrison challenged him as he strove to find his own voice as an author. Once, when he was in college, Morrison visited his school to read from her masterwork, "Beloved."

"My friends and I literally sat at her feet," Young said. "Of course, now and always, we all sit at her feet.

"She freed something in me," he added.

Morrison served many roles to the people around her, among them mentor, teacher, editor and mother, said American-Haitian novelist Edwidge Danticat. One of the more important ones, though, was friend, she said.

“You were the literary giant that was Toni Morrison, but to myself you were also Chloe Wofford,” Danticat said, calling Morrison by the author’s given name. “You allowed me to see both. You gave us both lullabies and battle cries. You urged us to be dangerously free.”

Toni Morrison was born Chloe Ardelia Wofford on Feb. 18, 1931, in Lorain, Ohio, the second of four children, the daughter of a ship welder and a homemaker, the granddaughter of sharecroppers.

Though Lorain was an integrated town, it wasn’t immune from racism. When Morrison was a toddler, her parents fell behind on their $4 monthly rent, so their landlord set fire to their house — while they were in it. Morrison doesn't remember the fire, she told the Washington Post in 1993, but her father refused to be intimidated, and she later passed that lesson to the characters she created.

“She refused to allow racism to overcome her," Remnick said at the memorial. "She shaped how we thought, how we felt, what we read, what we teach, how we see each other and how we see this troubled country.”

Life lessons, family stories and books were influences that shaped her into a visionary author whose gripping chronicles of the black experience inspired generations and rocketed her to critical achievement.

Morrison earned a bachelor’s degree in 1953 from Howard University, a historically black university in Washington, D.C.— and became known as Toni because "the people in Washington" couldn't pronounce her real name, she told NPR in 2015.

Morrison completed her master’s degree at Cornell University in 1955 and married Harold Morrison in 1958. They had two children, Ford and Slade, and divorced in 1964. She began teaching first at Texas Southern University, and then at Howard, beginning an academic career that would last five decades.

In 1967, she became the first black female fiction editor at Random House, where she published works by Muhammad Ali, Angela Davis, Gayl Jones, Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka. It was her second publishing job; the first was as a textbook editor in Syracuse, New York — a way to support the two children she was raising alone.

“She respected protest but she did not march. She edited," said Remnick at the service. "That was, for a time, her political work.”

Her 1970 debut novel, “The Bluest Eye,” tells the story of a black adolescent who lives in a violent household — and wishes for blue eyes. It’s set in Morrison’s hometown, post-Great Depression, and has consistently landed on the American Library Association’s list of challenged books for the “controversial issues” it addresses.

“She does it with a prose so precise, so faithful to speech and so charged with pain and wonder that the novel becomes poetry,” John Leonard wrote in a November 1970 New York Times review.

“I have said ‘poetry,’” Leonard added. “But 'The Bluest Eye' is also history, sociology, folklore, nightmare and music.”

Morrison’s writing became pioneering and prolific, earning her widespread critical acclaim. “Song of Solomon,” her third novel, won a National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction. She won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize in fiction for her best-known work, “Beloved,” published in 1987.

“Beloved” is the first in an African American history trilogy that includes “Jazz,” which takes place in 1920s Harlem, and “Paradise,” an Oprah’s Book Club selection. The novel, which tells the story of an African American who escapes slavery, spent more than six months on the New York Times bestseller list in hardcover alone. Winfrey starred in the 1998 film adaption of the novel.

Morrison wrote 11 novels. Her other works include “Sula,” “Tar Baby,” “Love,” “A Mercy,” “Home,” and “God Help the Child.”

“When I began, there was just one thing that I wanted to write about, which was the true devastation of racism in the most vulnerable, the most helpless unit in the society — a black female and a child,” she told the New York Times magazine in 1994. “I wanted to write about what it was like to be the subject of racism. It had a specificity that was damaging.”

More: Book of Toni Morrison quotes coming in December: 'The Measure of Our Lives: A Gathering of Wisdom'

More: Toni Morrison was our greatest writer, and her stories about race our most essential

More: Oprah Winfrey pays tribute to friend Toni Morrison: 'Long may her WORDS reign!'

Morrison in 1993 became the first African-American woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The prize, she later said, was unexpected.

“I felt a lot of ‘we’ excitement,” Morrison told the New York Times Magazine in 1994. “I represented a whole world of women who either were silenced or who had never received the imprimatur of the established literary world.”

Morrison joined Princeton University in 1989 as a humanities professor, retiring with emeritus status in 2006.

Though her career took her across the country and around the world, Morrison spent decades in Rockland County, where she lived when she died.

Story continues below the video

Morrison long called Grand View-on-Hudson home, even after her house there burned on Christmas Day 1993. Around 120 firefighters from two departments responded to the fire, the Associated Press reported, which gutted the four-story house but spared her manuscripts. Her son, Slade, who was alone in the house when the fire started, escaped unhurt. The house was rebuilt.

“People used to say, ‘How come you do so many things?’” Morrison told Publishers Weekly in 1987. “It never appeared to me that I was doing very much of anything; really everything I did was always about one thing, which is books. I was either editing them or writing them or reading them or teaching them, so it was very coherent.”

Former President Barack Obama awarded Morrison the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012.

“Toni Morrison was a national treasure, as good a storyteller, as captivating, in person as she was on the page,” Obama tweeted after her death. “Her writing was a beautiful, meaningful challenge to our conscience and our moral imagination. What a gift to breathe the same air as her, if only for a while.”

Morrison’s final book, “The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches and Meditations,” was published in February 2019.

Email: shanesa@northjersey.com Twitter: @alexisjshanes

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Toni Morrison celebrated at Cathedral of St. John the Divine in NY