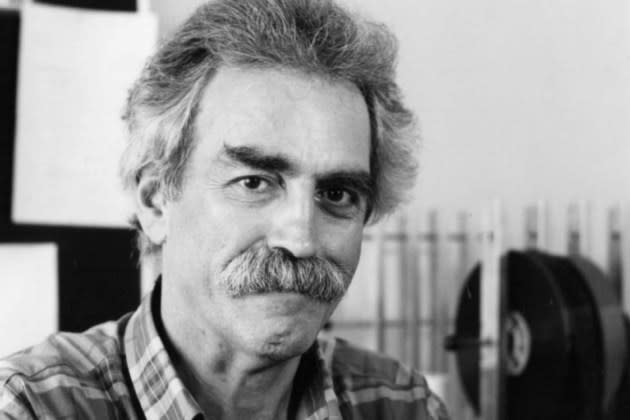

Tom Priestley, Oscar-Nominated Film Editor on ‘Deliverance,’ Dies at 91

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Tom Priestley, the British film editor whose work assembling the dueling-banjos sequence and hellish “squeal like a pig” attack in John Boorman’s Deliverance landed him an Oscar nomination, has died. He was 91.

His death on Christmas Day was only recently revealed.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Priestley also cut two other movies helmed by Boorman: Leo the Last (1970), which won the best director award at the Cannes Film Festival, and Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977).

He also edited The Great Gatsby (1974); Blake Edwards’ The Return of the Pink Panther (1975); That Lucky Touch (1975), starring Roger Moore; Voyage of the Damned (1976), featuring an all-star cast; and Roman Polanski’s Tess (1979).

Priestley was the only son of renowned British novelist and playwright J.B. Priestley, who wrote the classic 1945 drama An Inspector Calls for the theater and served as a BBC Radio broadcaster during the Dunkirk evacuation of World War II.

Upon its release in 1972, Deliverance became the fifth-highest grossing film of the year at the U.S. box office, earning nominations for best picture and director as well as film editing. It starred Jon Voight, Burt Reynolds, Ned Beatty and Ronny Cox as weekend adventurers who endure an unimaginable nightmare as they canoe down a Georgia river.

“A lot of the river stuff was in effect improvised because they were actually doing it,” Priestley recalled in a 2015 oral history of the film. “Let’s say the canoe going down a rapid might unexpectedly twist ’round or somebody’s hat would fall off — we incorporated that into the final cut.”

The thriller, however, couldn’t escape the cut of censors, with those at the British Board of Film forcing Priestley to remove the references to oral sex during the “squeal like a pig” rape sequence and having him shorten a local’s (Bill McKinney) sadistic death scene.

The director “plays his trump card and has editor Tom Priestley cut to a very tight close-up of Bill McKinney,” author Brian Hoyle wrote in 2012’s The Cinema of John Boorman. “The sudden effect of seeing the mountain man’s blackened teeth, his sweaty face and his cold eyes magnified in such a way, as he shouts for Bobby [Beatty] to squeal, is devastating.”

Priestley also cut between long shots and extreme close-ups and allowed the camera to linger on Voight’s face for a powerful reaction in the sequence that also featured another local actor, Herbert “Cowboy” Coward.

In an earlier scene, Cox performs a call-and-response banjo duet with a young native (Billy Redden) in an iconic musical sequence. Priestley’s edit builds as the song quickens and he masterfully cuts between no fewer than eight characters while keeping control of the pacing.

“We got two musicians who came down from New York, and we thought of all the variants of that particular theme that they could play,” he recalled. “Then I selected what I thought were the most appropriate bits and put them in.”

Deliverance was an adaptation of James Dickey’s 1970 novel of the same name. As a lieutenant in the Pacific War, the author read J.B. Priestley’s Midnight on the Desert on the journey home in 1946 and was moved by that book’s themes of coincidence and dreams.

During the filming of Deliverance, Dickey was invited into the makeshift editing suite at the Heart of Rabun Motel in Clayton, Georgia, unaware that the cutter next to him was J.B.’s son.

“A long time later, even just a few days before he died,” his son, Christopher Dickey, wrote in the 1998 book Summer of Deliverance: A Memoir of Father and Son, his father “would still be telling students about the book he read on the troopship [and] the man he met in Clayton. ‘The roots of coincidence plus the dream,’ he said in his breathless voice, enthralled by the possibilities.”

The editor screened portions of the movie for James Dickey, who had a cameo as a sheriff.

“Dickey’s character has this line in the final scenes — ‘I’d kinda like this place to die peaceful’ —which I think is the best in the whole film,” Priestley said. “It says so much. He knows there’s some strange business going on — let’s not stir it up.”

At its Atlanta premiere, then-Gov. Jimmy Carter was in attendance and remarked after the lights went up, “It’s pretty rough. But it’s good for Georgia … I hope.”

Born in London on April 22, 1932, Priestley studied at Cambridge University and had his interest in cinema piqued when he attended screenings hosted by legendary film critic Leslie Halliwell at the Rex Cinema in Leytonstone.

In an intriguing connection to his father, Priestley’s first credit was as second assistant sound editor on Dunkirk (1958), directed by Leslie Norman. He also was sound editor on Polanski’s first English-language film, Repulsion (1965).

Early film-editing gigs included Whistle Down the Wind (1961); Waltz of the Toreadors (1962), starring Peter Sellers; This Sporting Life (1962), with Richard Harris in his first starring role; Morgan! 1966) and Isadora (1968), both helmed by Karel Reisz; and one of history’s longest film titles — though it only ran 116 minutes — The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade (1967), directed by Peter Brook.

One of Priestley’s last jobs came on Michael Radford’s 1984, an adaptation of George Orwell’s 1949 dystopian novel. In another peculiar coincidence, J.B. Priestley’s name had been on Orwell’s list of suspected communist sympathizers that was sent to the propaganda unit of the British Foreign Office.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter