It's Time to Recognize 'Short Cuts' As a Masterpiece

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

By 1993, Robert Altman had given up gambling, but he hadn’t stopped placing big bets. Coming off the success of The Player—Altman's “fourth comeback,” he’d quip—he pushed all his chips in on an adaptation of nine Raymond Carver short stories. With the help of writer Frank Barhydt, he’d splice, tweak, and relocate each one, creating a sprawling, darkly comic mosaic of white working class life in Los Angeles. The resulting film, which followed a whopping 22 principal characters, clocked in at over three hours long. It was—as you probably know by now—called Short Cuts. The 1994 film began with pest control and ended with a natural disaster. A marketer’s dream!

Luckily for the film’s financiers, Altman knew how to sell the movie. “The common denominator is ketchup,” he’d say about what connected the various strands. The director was joking, of course. He was merely reflecting the absurdity of the question. Short Cuts wasn’t the sort of movie you could easily boil down to a single theme or argument. Sure, life's inherent chance, randomness, and transparent luck were top of mind for an auteur who’d seen firsthand how the winds of fate could propel you forward—only to push you back. Plus, in adapting Carver, it was impossible to avoid the subjects of infidelity, alcoholism, and mortality. But 30 years later, the reason Short Cuts endures as one of cinema's greatest ensemble pieces (maybe the greatest) is that it joins these stories not to advance some lofty thesis, but rather out of genuine interest in all of these characters and the performers who played them.

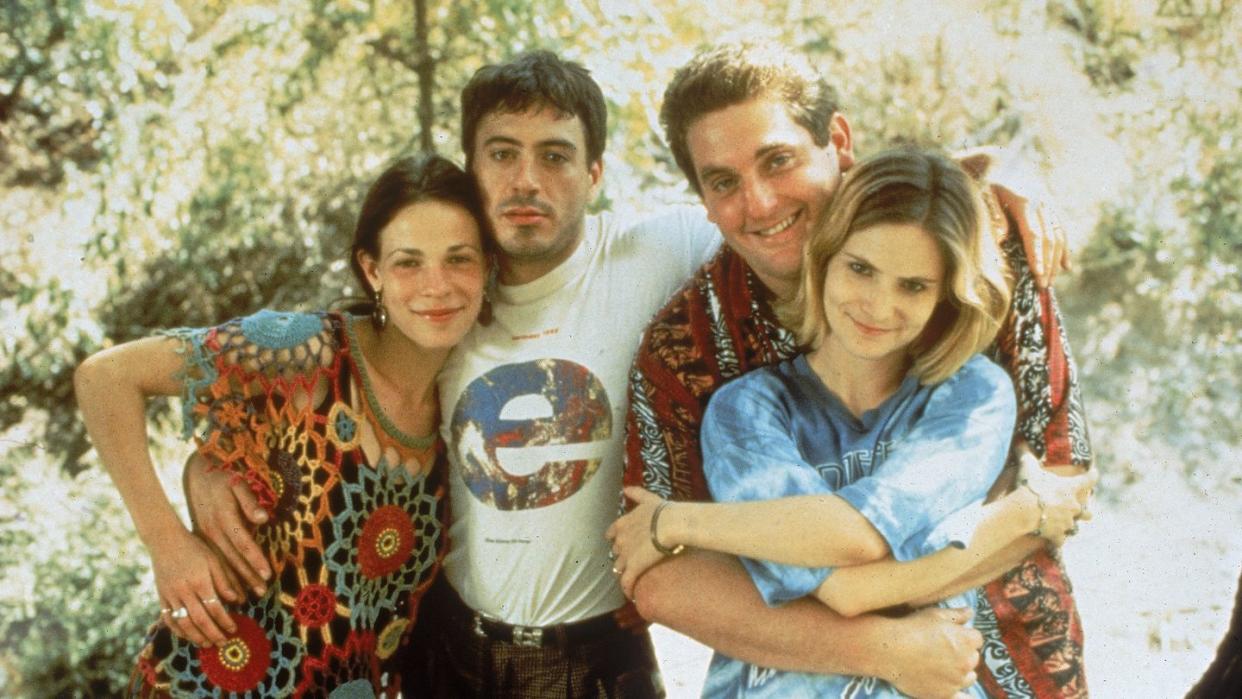

Thanks to his fondness for improvisation, Altman long carried a reputation as an actor’s director. Working with Carver’s stories, Altman and Barhydt took broad outlines of characters—occupations, marital dynamics, actions—and let the actors fill in the rest. He assembled a cast of wildly distinctive personalities—placing veteran screen legends (Jack Lemmon, Lily Tomlin) alongside promising newcomers (Andie MacDowell, Julianne Moore) and quirky musicians (Lyle Lovett, Huey Lewis). It helped that the material toed the line between literary and soapy—the dialogue rhythmic, the situations ripe with boozy melodrama. As an actor, these weren’t the sorts of straight-faced, serious parts that would get you recognized by the Academy. But these roles would allow you to ham it up with your dignity left intact—to really go for it as a shamelessly philandering police officer, a heavy-hearted cellist, or a destructively vengeful ex-husband. Looking back now, almost every member of Altman's ensemble has had a bigger role at some point. Yet, for many of them, their turn in Short Cuts is among the most memorable of their career.

The reason the cast leaves such an outsized impression likely has to do with Altman’s use of white space. Perhaps even more central to Carver’s work than all the drinking and cheating was the movie's stripped-down quality, which was achieved through the red pen of his editor, Gordon Lish. Carver was a master at creating tension through opacity, bringing narratives up to the edge of action and letting the reader fill in the gaps. In making Short Cuts, Altman used his fragmented form to achieve something similar. He cut from one story to the next right at that precipice, deliberately leaving out pivotal pieces of plot so the audience would be forced to imagine what they missed. “It seems to me if I can get everyone to do that—millions and millions of people making up stories of what happened in these gaps—it might be a whole new way of allowing the audience participation,” he said in a behind-the-scenes documentary about the making of the film.

Despite being a critical darling, Short Cuts didn’t exactly usher in a revolution of Hollywood trusting viewers’ imaginations. (Its meager box office performance probably didn’t help.) But it did influence countless films and filmmakers, with Paul Thomas Anderson being its most prominent borrower. Rewatching the film now, it’s hard not to be struck by how many of Anderson’s movies have lifted liberally from this single picture—Jennifer Jason Leigh’s phone sex work showing up in Punch Drunk Love, Julianne Moore going from bottomless in Short Cuts to a full-on porn star in Boogie Nights, and Magnolia following the film’s structure almost to a T. Altman could rest assured that at least one audience member was fully participating.

The director could also rest assured that—though Short Cuts offered a lot of meat on its bones for other filmmakers to pick at—taken in its totality, it was entirely inimitable. Short Cuts is a special confluence of this filmmaker working off these texts, all taking place in this setting, during this time period. Those last two factors—the film’s Los Angeles setting and early '90s environs—shouldn’t be overlooked. Despite being a film full of constructed sets, Short Cuts paints a specific portrait of the outer edges of Los Angeles’s sprawl, at a time before smartphones and social apps smoothed out the city’s texture. It’s a world of pools and pool cleaners, greasy spoons and lecherous patrons, limousines and dipso drivers. (Side note: in a movie full of perfect castings, Tom Waits's inclusion may take the cake). With the exception of the film’s overbearing whiteness, Short Cuts is the sort of movie whose datedness mostly works in its favor. It doesn't produce nostalgia, exactly, but a more complicated cousin to it. You wouldn’t want to live in this world, but hell, you’d gladly spend hours observing it.

Of course, it’s possible that beneath all the layers of Altman and Carver’s artistic stylings, your life bears more resemblance to these characters’ misadventures than you’d care to admit. After all, heavy boozing, infidelity, bruised egos, sudden tragedy, clowns—these things are still realities of American life. You just don’t usually see the whole big, messy kaleidoscope move before your eyes. When you do, it’s hard to know what to make of it. But more and more, the ambivalence coursing through Short Cuts is what I find special, timeless, and profound even about it. One second, things look hopelessly dark—and the next, you’re laughing. What a film. What a world.

You Might Also Like