'It's time to put a spotlight on Carl Erskine': Dodgers star's quiet fight for human rights

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

ANDERSON -- The basketball court was in a back alley. It sat empty waiting for kids who had finished their chores after school or who had gotten up early enough to play as the sun rose. Carl Erskine went there every chance he got.

It was the 1930s in Anderson where, 10 years before, the Ku Klux Klan had a stronghold, as it did across the state and much of the nation. Racism was rampant as Erskine came to that court in 1937, a 10-year-old white boy with nothing to prove. Just to play.

"And with every societal force pushing Carl in another direction, here on a basketball court in a back alley, he befriends a 9-year-old Johnny," said filmmaker Ted Green, whose documentary on Erskine, "The Best We've Got: The Carl Erskine Story," will premier Thursday.

Johnny was "Jumpin" Johnny Wilson, as he later became known in Anderson, a high school basketball superstar who along with Erskine wowed crowds of more than 5,000 at the Wigwam gym.

Erskine and Wilson, who was Black, became more than teammates. They became friends. Great friends. They remained friends for 80 years until Wilson died in 2019.

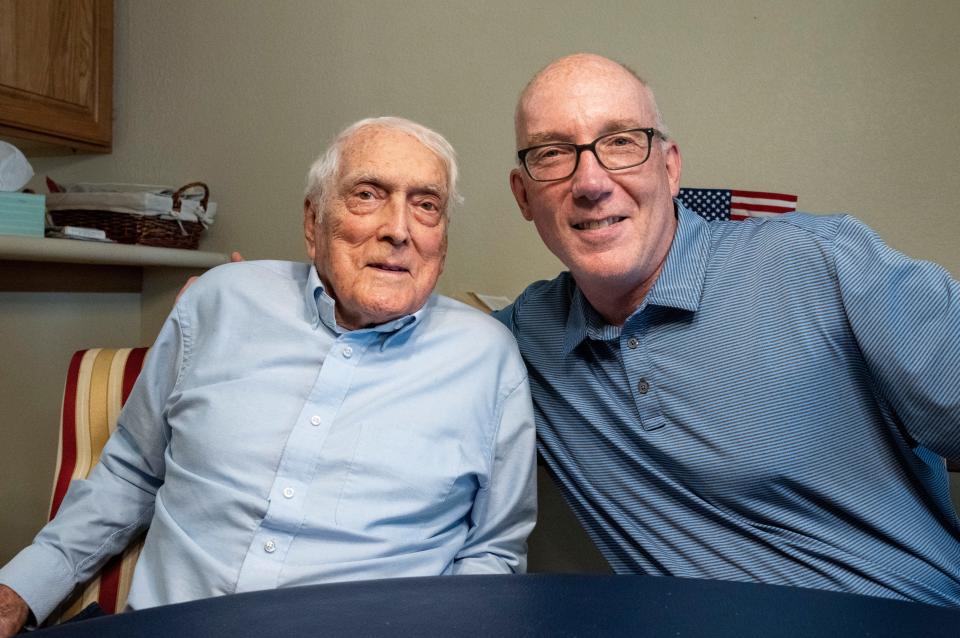

Throughout his life, 95-year-old Erskine remembered that friendship, how desperately he wanted Wilson to be treated as he was treated at restaurants, by coaches, by anyone. And quietly, behind the scenes, Erskine used humility and grace in a push for racial equality.

'If he acted up, he acted up.' Just like every other kid acts up.

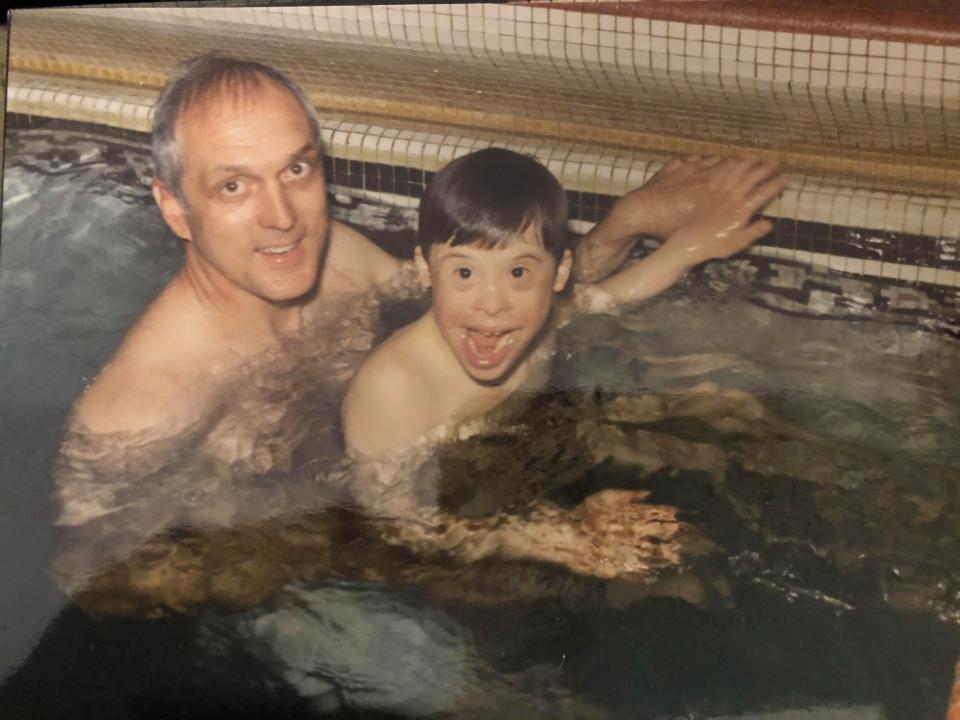

Jimmy Erskine was born in 1960 with Down syndrome. It was a time when many doctors told parents that babies with Down syndrome should be sent to an institution, that they would be a societal hindrance, that they would disrupt family life.

Carl Erskine had just finished a stellar 11-year career with the Brooklyn, then Los Angeles, Dodgers as a pitcher. He pitched the first nationally-televised no-hitter, played in five World Series (winning in 1955), set the Series single-game strikeout record, threw two no-hitters and pitched the Dodgers’ first game in Los Angeles. In 1959, he pitched his last game and came home to Anderson.

The next year, Jimmy was born.

Erskine and his wife, Betty, ignored what doctors said and they took Jimmy home. They were not going to do what other families had done before. They raised Jimmy just as they did their other three children, Danny, Gary and Susan.

"They let him fly. They took Jimmy out with them wherever they went, to church, to restaurants," said Green. "It was always Jimmy was there and if he acted up, he acted up." Just like every other kid acts up.

Green says the Erskines blazed a trail for other families with children who had special needs. They showed quietly though their actions how to raise a child with intellectual disabilities.

But Erskine didn't just make life better for Jimmy. He took to another fight, a fight to make lives better for all people with special needs. He was a fierce advocate for educational opportunities and for Special Olympics.

"Carl Erskine has helped to affect such massive change through humility, through grace, through human leadership," said Green. "He has spent his lifetime propping up others. It's time to put a spotlight on him."

'One of the great human-rights champions of our time'

"The Carl Erskine Story" premiers at Paramount Theatre in Anderson on Thursday night. The show is sold out; tickets for future screenings are available.

Along with the Indiana Historical Society, Ted Green Films produced the documentary that celebrates Erskine, the last of the Brooklyn Dodgers' Boys of Summer, a man Green calls "one of the great human-rights champions of our time."

"I like to tackle stories that celebrate the triumph of the human spirit," said Green, who is married to IndyStar sports director Jenny Green.

Along with WFYI Public Media, Green produced "Attucks: The School That Opened a City." And with cinematographer Mika Brown, "Eva: A-7063," a story of Eva Kor, a Holocaust survivor turned global advocate for forgiveness and healing.

"After those, I really didn't know where I was going to find that," said Green. "That story of human triumph."

Then Green remembered a tip he got from Bobby "Slick" Leonard when he was producing a documentary on the late Indiana Pacers coach. "You have to do a film about Carl one day," Leonard told him.

Green started looking into Erskine, then he met with him. "I was amazed and off we went."

"If you look around at what has been going on the last couple of years, so much vitriol, political (dissension), COVID," said Green. "With that in mind, I was just so drawn to this guy in Anderson, Indiana."

The documentary shares the story of Erskine and the pivotal role he played in two of the great human rights movements of the time. He helped break down racial barriers as a teammate and close friend of Jackie Robinson and he fought for people with intellectual disabilities, their acceptance and the services available to them.

“In baseball circles and among many in Indiana, Carl has been revered for decades,” Green said. “And we’ll show that in the most fun, comprehensive light yet. But the true beauty of the film will be what Carl has done, quietly but so powerfully, to integrate society and make all feel accepted and welcome.

"He is a living testament to the ability a humble, dedicated person has to make a mountain of difference."

'One of the first white allies'

Erskine was born at home in 1926, the son of a grocery store manager, who later became a factory worker, and a stay-at-home mom. He grew up in what he called a "mixed neighborhood" in Anderson.

His best friend was Wilson. The two were joined at the hip. They walked to school together every day and hung out after. They played sports together and told each other their deepest secrets. Erskine didn't realize it at the time, but Wilson would shape his views on race. And later in his life, someone would notice that.

Erskine was in the Brooklyn Dodgers locker room when he heard a guy come up behind him, Erskine told IndyStar in 2015.

"Hey Erskine, how come you don't have a problem with this Black and white thing?" The voice belonged to Dodgers teammate Jackie Robinson.

"I said, 'Well, I grew up with Johnny Wilson,'" Erskine recalled. "'I didn't know he was Black. He was my buddy. And so I don't have a problem.'"

Wilson's niece, Leisa Richardson, grew up in Anderson and was a cheerleader with Erskine's daughter, Susan. The two became fast friends, not realizing in junior high the connection Richardson's uncle had to Susan's father. They soon learned that "unbeknownst to us, fate had brought us together," Richardson said.

"He and my uncle were friends. As a kid you don’t pay attention to what your older adult family members are doing and what their connections are," she said. "They are just who they are."

But the first time Richardson hung out at Susan's house, the girls realized her uncle was one of her father's best friends.

"But even then we did not realize how cool that friendship was," Richardson said, "and that the generations continued what my uncle and Mr. Erskine started." Richardson and Susan are still great friends.

Erskine and Wilson's bond only grew as they got older. They started going to schools to speak about their friendship.

"They weren't there to shame people or to scold people. They were just there to show people, to light a path," said Green. Just as Erskine had done so many years before, lighting a path through his friendship with Robinson.

Erskine was one of America's first white allies, according to Richard Lapchick, who has been described as the “racial conscience of sports."

The year Robinson died, he said that no other Dodger understood more about what was happening than Erskine. "And by that, he meant racially," said Green. "Carl was probably Jackie's biggest supporter on the team."

In Erskine's 2012 book, "The Parallel: Witnessing Two of the Greatest Social Changes in My Lifetime," he details the similarities of the journeys of Robinson and his son Jimmy. How they both overcame prejudice and rejection to achieve acceptance and inclusion.

Erskine writes of how he witnessed the silent perseverance of one man change society. The lessons he learned from Robinson became part of his legacy when Jimmy was born with Down syndrome in 1960, Erskine said.

And Erskine would follow in Robinson's footsteps, fighting through actions not loud words, by silent perseverance to change society for people like Jimmy.

To make sure they didn't just live, but they thrived.

'Their model of raising Jimmy was phenomenal'

Dr. Richard Schreiner first met Erskine more than 40 years ago at a support conference for parents of children with Down syndrome. Erskine was the luncheon's keynote speaker.

The two sat at the same table together. Schreiner, at the time, was a neonatologist at Riley Hospital for Children. He went on to become the hospital's physician-in-chief. In 1988, his daughter Kelley was born with Down syndrome.

As Schreiner sat at that luncheon, Erskine told him the story of he and Betty's decision to not put Jimmy in an institution. At Riley, Erskine said Dr. Morris Green told them: "Take him home and love him like any other child."

In the early part of Jimmy's life, he didn't speak much and, when he did, it was hard to understand, Schreiner said. Erskine told the story of Jimmy frequently sneaking over to the neighbor's house when they weren't home, setting the alarm off and the police being called.

After asking Jimmy repeatedly to stop doing that "finally Carl told Jimmy, 'If you do that again, I'm going to give you a spanking,'" Schreiner said. "Well Jimmy did it again and Carl told him, 'Alright Jimmy it's time for your spanking.'"

For the first time in his life, Jimmy spoke loud and clear, said Schreiner. He looked at Erskine and said "No thank you."

What the Erskines did for Jimmy may seem usual today, but it wasn't then, said Schreiner. "People with those kinds of disabilities, they were institutionalized. They didn't get out."

Those institutions were often horrendous, many crammed with thousands of patients and terrible care. They were often filthy and residents were mistreated, left sitting with nothing to do and sometimes not fed.

"It was heartless treating them as if they weren't even human beings," said Green.

During a time when there was no schooling or services available to Jimmy, the Erskines started grassroots programs and pushed for legislation, said Green. That ultimately led to the abolishment of prison-like institutions and steps toward full integration into society, changing the paradigm for children with special needs.

"What they did, their model of raising Jimmy," said Schreiner, "it was just phenomenal."

Jimmy is 62 and, through his lifetime, Indiana has gone from the worst state in America for people with intellectual disabilities to near the top, Green said.

"And everybody who would know, while it has taken a village for such a change, the No. 1 reason it happened was No. 17," he said, "Carl Erksine."

'He wants the best for every single person'

Gary Erskine was with his father and mother as they watched "The Best We've Got" for the first time. "We were over the top," said Gary. "The way the film shows them, they're the exact same way."

After finishing the film, Betty Erskine made the comment, "I hope we're as good as people think we are."

They are, said Gary, and then some. The Erskines life was so much more than baseball. In 95 years, Erskine played 11 in the MLB; that's a blip. What he did with the rest of his years are what truly counts, said Gary.

"My dad, he loves and thrives on people," he said. "He wants the best for every single person. That's his mission. He doesn't preach it loud and my mom is the same way. They just naturally uplift people."

As Green made the film, he spent some time at Robinson's grave. On his tombstone, it reads "A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives."

"I believe Carl Erskine embodies that more than embody else," Green said. "This is a guy who leads with humility, leads with grace. He doesn't lead with the bombast you hear of most people today. His impact is all the more powerful because of this.

"He has spent his life celebrating others. Well, you know, it's time we celebrate him."

More about 'The Best We've Got: The Carl Erskine Story'

Former Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels inspired the film’s title. When presenting Erskine with a Sachem Award, the state’s highest honor, Daniels said, “He’s the best we’ve got.”

Special Olympics Indiana is contributing an educational component to the project, the Erskine Personal Impact Curriculum (EPIC), which will be presented by Duke Energy and distributed to schools statewide. The curriculum’s lessons and activities promote social and emotional learning for every age level, using stories and experiences from Erskine’s life about friendship, dignity, inclusion, perseverance, appreciation, leadership, empowerment and social change.

For information on the film, the EPIC program and tickets, visit: https://www.carlerskinefilm.com/

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @Dana Benbow. Reach her via e-mail: dbenbow@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Carl Erskine was Dodgers great. His fight for human rights was greater